Countries around the world are grappling with an alarming rise in measles, a deadly, yet vaccine-preventable disease. Last month, the US CDC issued a health alert over rising cases across the US, where 113 measles cases have been reported this year, already exceeding the total number of cases last year. And across European and Central Asian countries, measles cases went from under a thousand in 2022 to more than 30,000 in 2023.

As a survivor of a vaccine-preventable disease, I understand more than most just how important it is to reverse this trend. Six months after I was born in Bombay, India, I contracted polio, which left me paralyzed from the hips down. At the time, polio vaccines weren’t widely available in India, and as a result, I never received the life-saving drops that could have protected me from this crippling disease.

I wasn’t alone – in the 1970’s when I was born, India struggled with almost 200,000 polio cases each year. This isn’t surprising—before vaccines became common, diseases we hardly think about now, like polio, plagued the world and caused unnecessary death and immense suffering. Before the measles vaccine was introduced in the early 1960’s, the disease used to kill an estimated 2.6 million people annually.

To ensure all children benefit from the power of vaccines and are protected from the ravages of preventable diseases like measles, we must heed the lessons of successful vaccination efforts, such as the global push to eradicate polio.

Since a global effort to eradicate the disease through vaccination began in 1988, polio cases have been reduced by 99.9%. And a decade ago last week, one of the seemingly insurmountable challenges to the eradication effort was achieved: India, a country with limited means and facing unlimited challenges, was certified as polio-free, along with the entire South-East Asia Region.

Today, countries are pushing to replicate India’s success in the virus’s remaining strongholds, particularly in Pakistan and Afghanistan, where only 12 cases were recorded last year. I believe we can get to zero cases anywhere in the world by fully harnessing the power of vaccines, learning from India’s remarkable story, and refusing to concede defeat.

India was once deemed the most difficult country in the world to end polio. Poor sanitation and overcrowded living spaces allowed the virus to spread easily, infecting hundreds of thousands of children each year, making it nearly impossible to control.

Strong support from the Indian government coupled with a new global push to eradicate the disease in the late 1980s marked a turning point. Soon after, vaccination campaigns led by millions of dedicated vaccinators and community mobilizers on the frontlines resulted in the repeated distribution of life-saving vaccines to nearly every child in the country. In the years leading up to the last case, a staggering 1 billion doses of the polio vaccine were distributed to 172 million children annually. Mass vaccination campaigns, requiring over 2 million vaccinators at a time, reached every household.

After the last case, India was determined to keep the country polio-free. Impressive surveillance networks and immunization campaigns continued on, which I got to witness in 2015 when I returned to India with Rotary International. Administering two drops of the vaccine to babies in the backstreets of New Delhi was a profound, full-circle moment for me – from my mother’s lack of access to the vaccine, to my own struggle with polio, to ensuring my daughter received the necessary immunization.

Today, strategies pioneered in India are being used to eliminate wild polio from Pakistan and Afghanistan, the final two endemic countries for wild poliovirus. And in both countries, promising trends that were seen in India, such as fewer strains of the virus and smaller outbreaks, suggest that the virus may be permanently on its way out.

There’s no denying that there are still serious challenges to vaccinating all children in areas where the virus is still a threat – from complex humanitarian emergencies, ongoing conflicts, a lack of trust in governments and science, to difficulties reaching remote populations.

The push to end polio today has relied on continuing to innovate. Strategies started in India have continued to be refined to meet today’s challenges – from vaccinating hard-to-reach populations through community microplanning and empowering women health workers to address vaccine hesitancy have been refined and improved. And in particularly fragile settings, recent collaborations with humanitarian organizations have demonstrated the value of integrating polio initiatives with broader health services.

What gives me hope is that today, we have the tools and strategies needed to end needless suffering caused by polio and other preventable diseases around the world. What we still need is the continued resolve to get us there. As India’s blueprint showed us, unwavering support from donors and global organizations, coupled with the ongoing determination from communities, local leaders, and national governments will be essential.

With more countries around the world heading into elections this year than ever before, I hope to see policymakers in the US and abroad continue to commit to eradicating polio and strengthening access to other life-saving vaccines. With the right level of commitment and resources, we can end polio everywhere and protect children against other preventable diseases.

By Minda Dentler

Minda Dentler, a 2017 Aspen Institute New Voices Fellow, is a polio survivor, a global health advocate, author, and the first female wheelchair athlete to complete the Ironman World Championship in Kona, Hawaii.

25-year-old Geeta, a mother of three, has her priority clear – making 300 bricks a day. “I don’t have time to even think of taking my children to the Aganwadi centre for routine immunization,” she admits.

25-year-old Geeta, a mother of three, has her priority clear – making 300 bricks a day. “I don’t have time to even think of taking my children to the Aganwadi centre for routine immunization,” she admits.

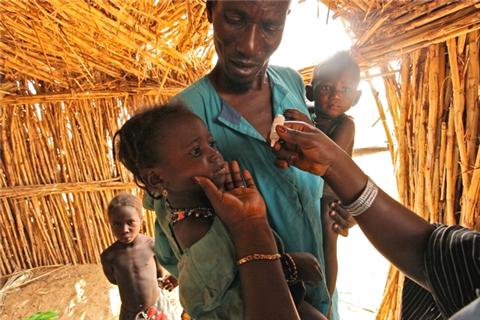

The community leaders, or ‘Hardos’, among the Fulani people in Katsina State, Nigeria, have come together under the Myetti Allah organization to help the GPEI vaccinate the hardest-to-reach children against polio, with spectacular success.

The community leaders, or ‘Hardos’, among the Fulani people in Katsina State, Nigeria, have come together under the Myetti Allah organization to help the GPEI vaccinate the hardest-to-reach children against polio, with spectacular success.