Women make up only 28% of the workforce in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM), and men vastly outnumber women majoring in most STEM fields in college globally. On March 2011, the Commission on the Status of Women adopted a report at its 55th session to promote women’s equal access to full employment and decent work. Two years later, on 20 December 2013, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution in which it was noted that it is imperative for women and girls to be involved in STEM.

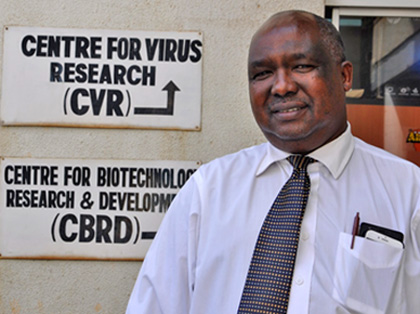

On the International Day of the Women and Girls in Science on 11 February 2023, Rosemary Mukui Nzunza, the head of the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) at the Centre for Virus Research, the Kenya Medical Research Institute, shared her story of pursuing a career in science. She is currently in the final stages of working towards earning her PHD in Molecular Medicine.

Rosemary explains she would like girls and women to know there is enough room for everyone in science; and women should maintain healthy competition in science and go as far as they can. It also helps to look for mentors and people you can admire and follow so they inspire you to keep growing, she says.

“Research has earned this name as it means you need to go back and search over and over again,” Rosemary says. “Besides, there are no ceilings in science – girls and women can go as far as they want to.”

As a child, Rosemary Nzunza spent her free time pounding leaves, roots and tubers, using thick wooden sticks to create “medicine”. Her creativity, curiosity, and love for finding explanations for how things work made her want to teach science − or at least work in the world of science.

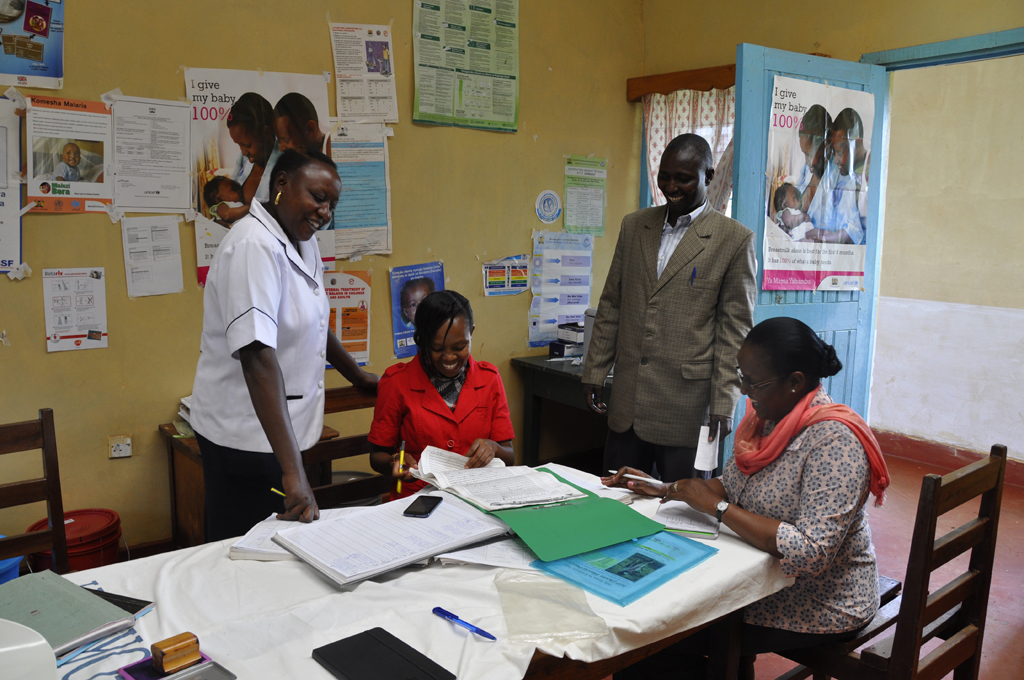

Rosemary never has a dull day at work. She currently serves as Senior Research Scientist and Head of Division of the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) at the Centre for Virus Research at KEMRI. Her role entails monitoring quality assurance in laboratory work and biosafety and overseeing the work of the different units at KEMRI. She also represents the laboratory in key national committees in Kenya: the National Committee on Containment of Polioviruses (NTF), National Polio Certification Committee (NPCC), National Measles and Rubella Technical Advisory Committee (MTAG) and the National Polio Experts Committee (NPEC).

Rosemary joined the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Laboratory 23 years ago, starting her career as a research officer with the US Army Medical Research Directorate (USAMRD). In 2006, Rosemary earned her Master’s in Applied Microbiology. Back then, she was one of just two women at the unit who had postgraduate degrees under their belts. She reflects on how her male colleagues looked up to the two women as mentors, which made them feel really proud. But she notes that this also meant they were in charge of all laboratory procedures, laboratory quality, and the troubleshooting, which was quite challenging at the time.

Polio still exists

When Rosemary joined KEMRI, she was surprised to learn that the institution was tasked with supporting polio eradication. She had thought polio had been wiped out from the world a long time ago.

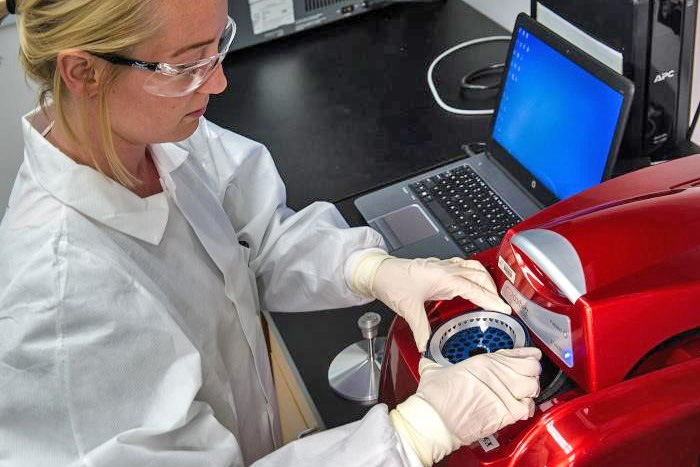

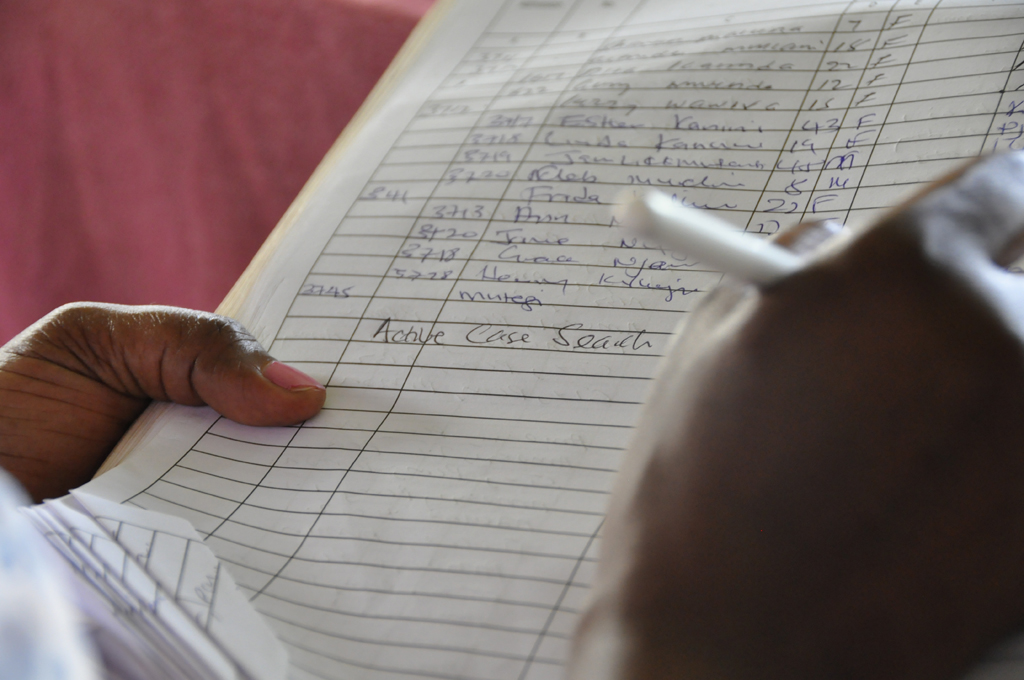

Presently, Rosemary and her team at the KEMRI Laboratory work meticulously on testing samples of measles, polio and rubella. They know their work is integral to saving children from the harsh effects of preventable diseases, such as polio. Their work on polio is two-pronged: they have been testing samples for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) since 2000 and environmental surveillance (ES) since 2013. AFP is defined by the acute onset of weakness or paralysis with reduced muscle tone in children. There are many infectious and non-infectious causes of AFP. Polio, caused by wild poliovirus (the naturally circulating strain) is one cause of AFP, and so early detection of AFP is critical in containing a potential outbreak. Respiratory and stool samples are optimal for enterovirus detection. Environmental surveillance complements AFP surveillance. It entails collecting and testing wastewater samples and can help in the early detection of and response to polioviruses. By identifying polioviruses swiftly, countries can stop their spread.

At times, the 17-member team receives an overwhelming number of samples at once from countries in the Region facing polio outbreaks. This presents a challenge, as it might mean the team needs more supplies for testing and needs to work longer hours to deliver timely results.

Once they have tested samples, they interpret results for each and send them back to the country to guide further and swift action. By 3 pm Eastern African Time every Friday, the KEMRI team works to send summaries of test results on measles, polio and rubella to the national surveillance office within Kenya’s Ministry of Health and other partners. These include the WHO Regional Office for Africa (AFRO); WHO Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (EMRO); WHO headquarters; and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Management during COVID-19 was a challenge

One of the most difficult times Rosemary has faced in her career was the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. During that period, she felt like health workers were carrying the weight of the entire world. In Kenya, her team was tasked with supporting the government in conducting COVID-19 tests. At the time, everything seemed so uncertain. Personal protective equipment (PPE) kits looked frightening, people all over the world were dying of COVID-19, and procedures and test kits still needed validation. She remembers thinking to herself, “Someone has to do this. And it’s us, here, now.”

Photo credit: WHO/L. Dore

Similar to the situation health workers around the world faced, her team was also afraid of being infected with COVID-19, especially before vaccines were available. Rosemary recalls the team staying at work for long, tiring stretches, partially to avoid contact with their families, out of fear of inadvertently putting them at any risk of being infected with COVID-19. Teammates would huddle together and discuss their after-work protocol at home: slip in through the back door, disinfect clothes, clean up rigorously, take a shower, avoid all contact with loved ones, and set off on the same routine the next day before anyone woke up.

She split the team into two shifts to manage the immense workload. The aim was to prevent the team from burning out and ensuring their new work on COVID-19 didn’t slow down the other, crucial support to disease elimination that still needed to be carried out. Looking back now, Rosemary credits the support she and her team received from the management at KEMRI, colleagues, partners, friends and family with helping them stay focused and rise to the unprecedented challenges of that time.

She also attributes the success of the KEMRI EPI Division Laboratories to support from institutions across the world, including the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) partners. She says she has always been impressed with the incredible support from WHO and the rest of the GPEI partnership, where diverse agencies come together to tackle one goal.

More mentors needed for girls to join and grow in science

The young lady who stepped foot out of her village in Machakos county – in Kenya – for the first time when she left for Eldoret to earn her Bachelor’s in Science Education has come a long way. She is keen to see other girls and women take their place at the forefront of science – but only if they have a passion for this field, she adds. Breaking into a laugh, she says there’s a lot to read and keep up with every single day. After all, science is about changing the world.