In Afghanistan this year, staff from the non-governmental organization Care of Afghan Families collected 420 blood samples from children under 4 at the Mirwais Regional Hospital in Kandahar province. The aim? To find out whether polio vaccination campaigns have been reaching enough children, and whether the vaccines have been generating full protection against this paralysing disease. These ‘serosurveys’ showed that immunity in Afghanistan is high – and also identified where vaccination campaigns need to reach out further.

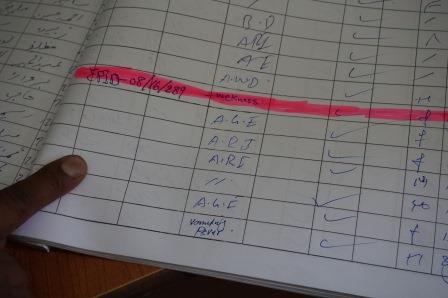

Whenever a polio vaccination campaign takes place, a purple dot of ink is painted onto the little finger nail of every immunised child to show that they have received the lifesaving vaccine. This data is collected and allows people to monitor the campaign and know exactly where children have been reached.

Now, with more children being vaccinated than ever before, the polio eradication programme needs to know more than how many children are being reached: we need specific data on where children are being missed.

Serosurveys testing for immunity

Serosurveys are simple tests of the serum in a child’s blood, which measures their immunity (or seroprevalence) to different diseases. The polio eradication programme uses this test to see what level of protection a child has against wild poliovirus types 1, 2 and 3, allowing them to assess whether the vaccination campaigns are reaching enough children, enough times, to give them immunity.

At the Mirwais Regional Hospital, the children tested were from a diverse range of provinces. Their results were sent to Aga Khan University for initial testing, and then sent for further analysis to one of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative partners, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. Through mapping both where they live and their immunity results, scientists at both institutions helped polio eradicators to discover the areas where a child is at most risk of being missed by vaccination campaigns.

Serosurvey results can be crucial for planning campaign strategies – making sure that every last child is reached, no matter where they live.

For Ondrej Mach, team lead for clinical trials and research in the WHO’s Polio Eradication Department, serosurveys “… are increasingly important for eradication efforts, allowing us to form an accurate picture of our progress so far, and the locations where we are being most effective.”

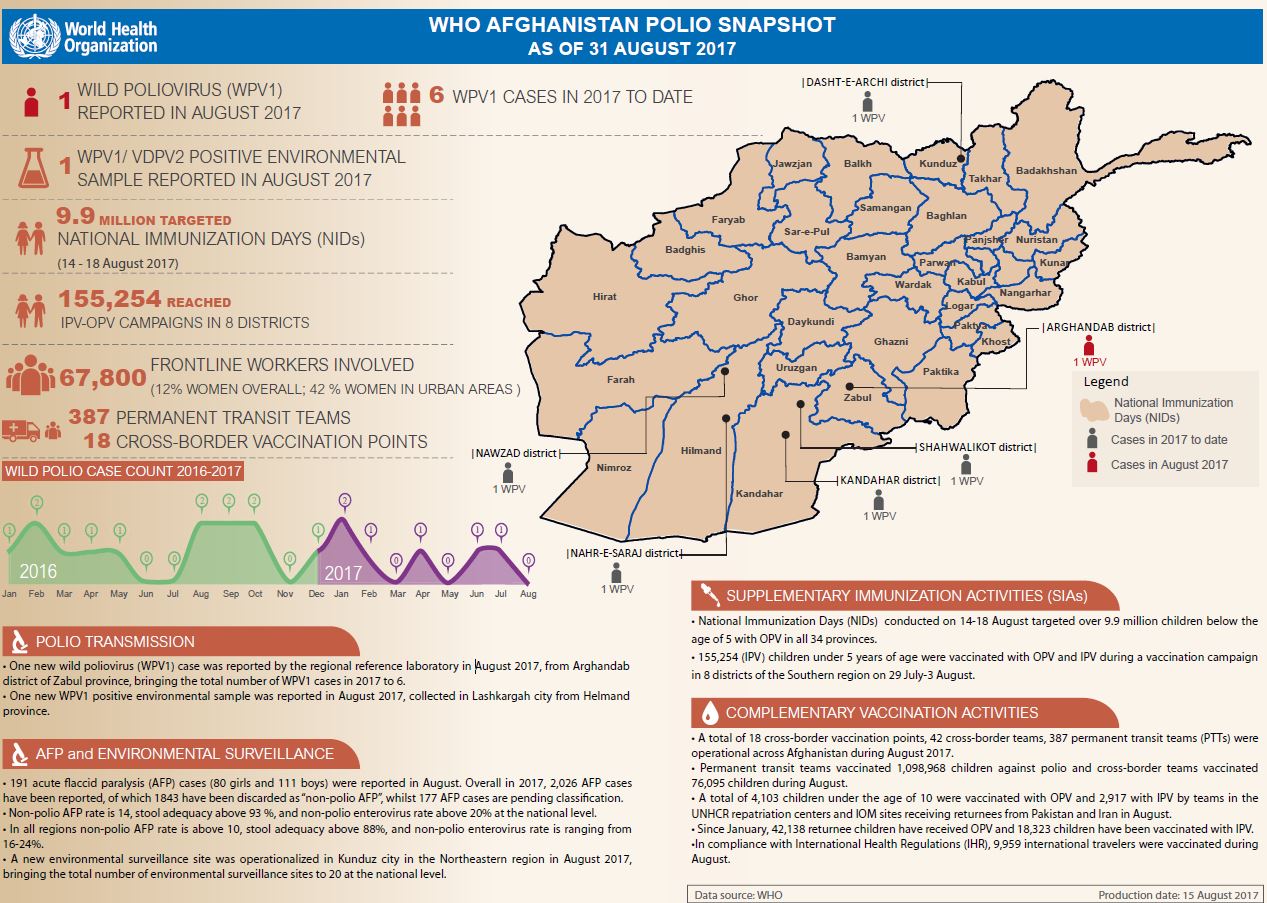

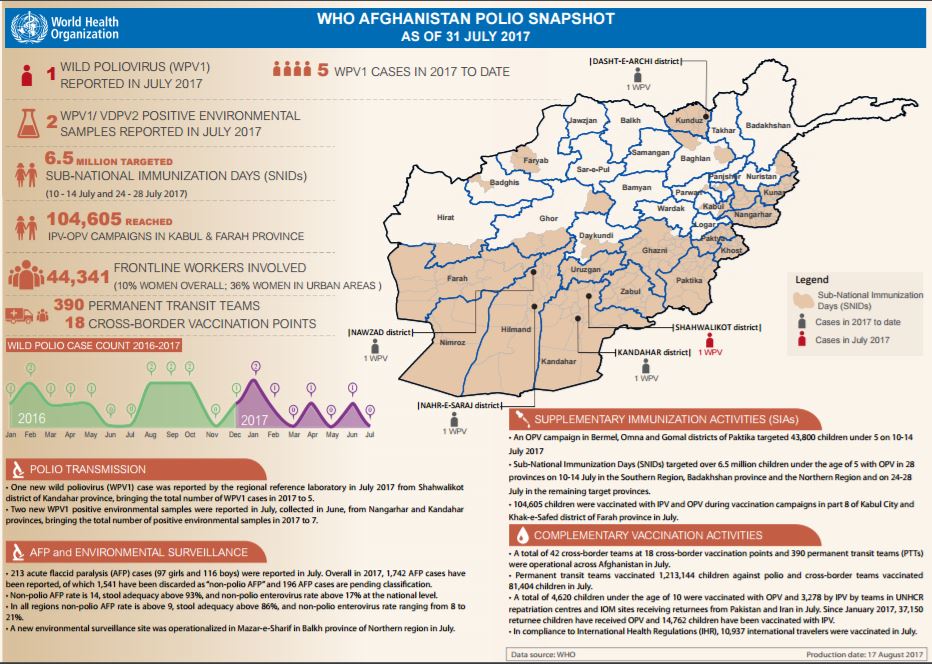

High immunity in Afghanistan

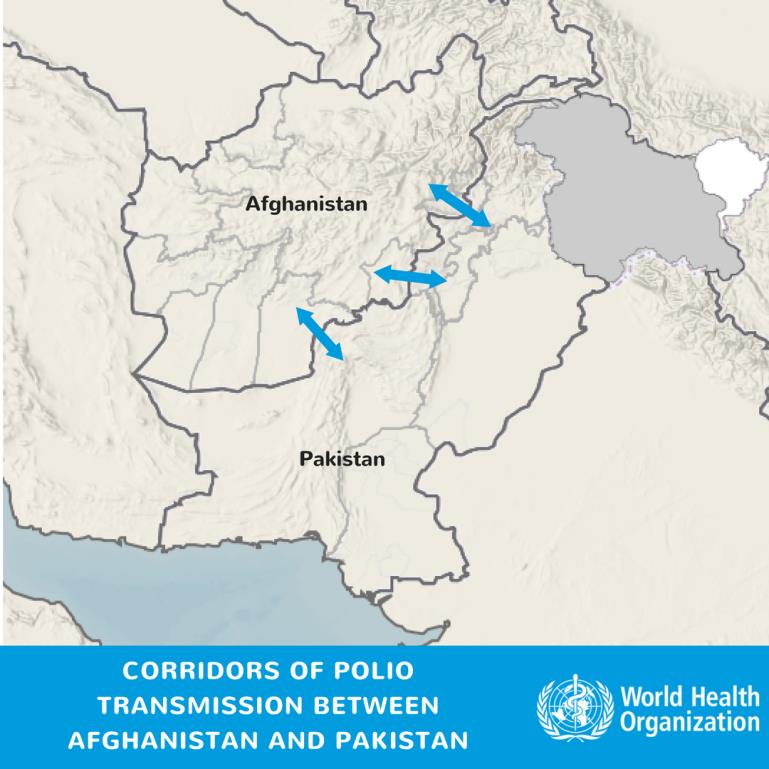

The Mirwais serosurvey proved that Afghanistan is closer than ever to eradicating polio, with more than 95% of children surveyed immune to wild poliovirus type 1, the virus type still circulating in some areas of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria, and more than 90% immune to type 3, which hasn’t been found anywhere in the world since November 2012. The tests also pointed to where gaps in immunity are, so that missed children can be found and protected.

These results are a strong reflection of the devoted work of polio vaccinators and community workers throughout the country, using their expertise to reach into every family, and spread awareness of the importance of polio vaccination.

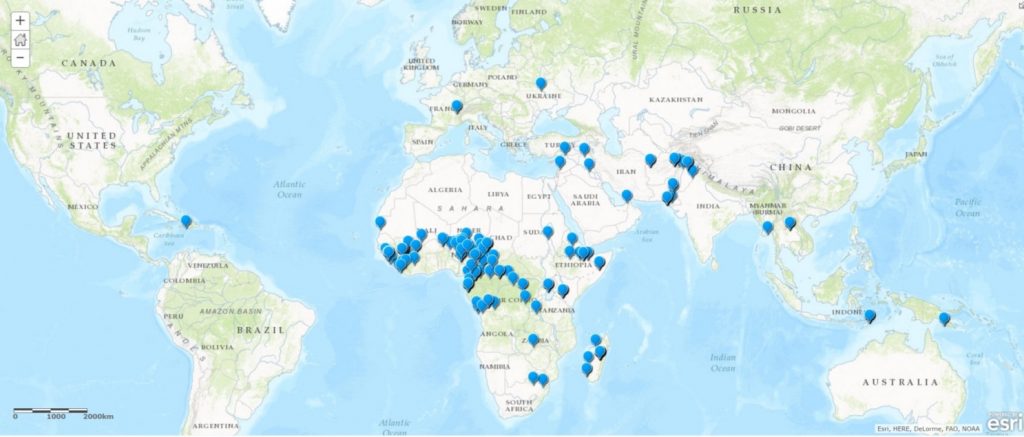

Using serosurveys in at-risk countries

As in Afghanistan, serosurveys are increasingly used in other countries where polio remains or poses a threat, to help identify the last remaining pockets of under-immunized children in high risk areas. This is especially important because with polio in fewer places than ever before, it is these unreached children that will take us over the finishing line.

By getting an increasingly accurate picture of where vaccination campaigns are operating successfully, as well as where the programme needs to renew efforts, we can move further towards the goal of reaching every child.

This helps us reach our ultimate goal – ensuring that every last child, everywhere, can be polio free.

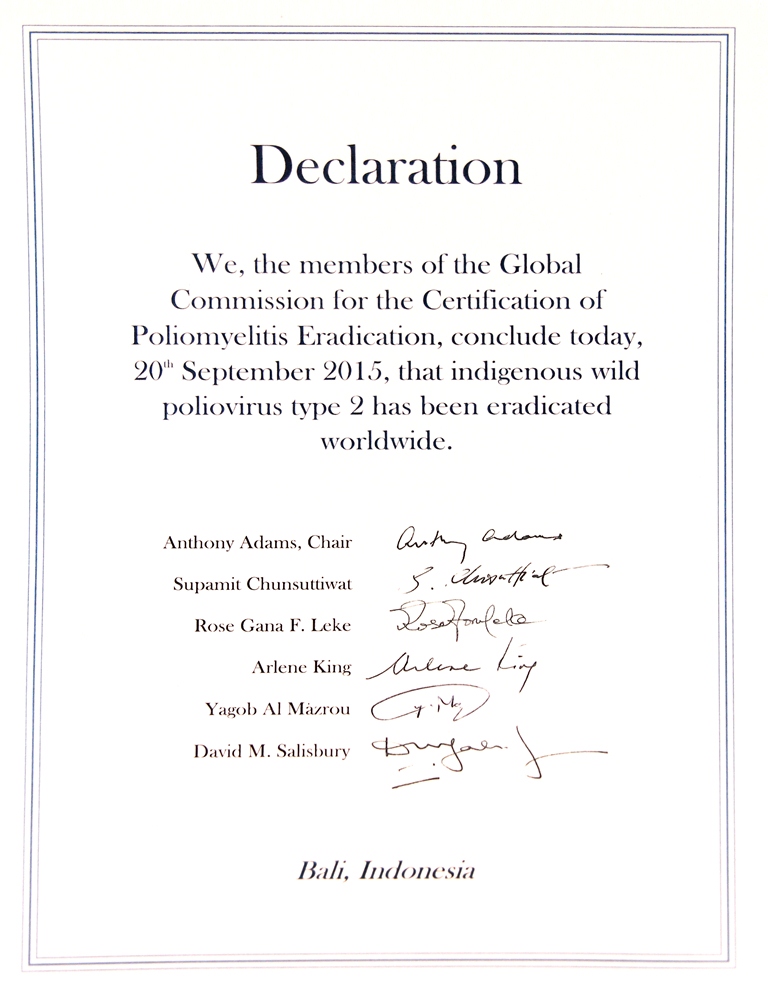

20 September, Bali – In an important step towards a polio-free world, the Global Commission for the Certification of Poliomyelitis Eradication (GCC) today concluded that wild poliovirus type 2 (WPV2) has been eradicated worldwide. The GCC reached its conclusion after reviewing formal documentation submitted by Member States, global poliovirus laboratory network and surveillance systems. The last detected WPV2 dates to 1999, from Aligarh, northern India.

20 September, Bali – In an important step towards a polio-free world, the Global Commission for the Certification of Poliomyelitis Eradication (GCC) today concluded that wild poliovirus type 2 (WPV2) has been eradicated worldwide. The GCC reached its conclusion after reviewing formal documentation submitted by Member States, global poliovirus laboratory network and surveillance systems. The last detected WPV2 dates to 1999, from Aligarh, northern India.