Brazzaville, May 14, 2024 – Following thorough assessments in Malawi and Mozambique, an independent Polio Outbreak Response Assessment Team (OBRA) today recommended the closure of the wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) outbreak in Malawi and Mozambique, marking a significant milestone in the fight against polio in the African region.

The last WPV1 case in the African Region, linked to a strain circulating in Pakistan, was reported in Mozambique´s Tete Province in August 2022. A total of nine cases were detected in Mozambique and neighbouring Malawi, where the outbreak was declared in February 2022. In a coordinated response, more than 50 million children have been vaccinated to date against the virus in southern Africa.

The meticulous evaluation carried out by the OBRA team included two in-depth field reviews and supplementary data review, concluding that there is no evidence of ongoing wild polio transmission. The assessment considered the quality of the outbreak response, including the overall population immunity, supplementary immunization campaigns, routine immunization coverage, surveillance systems, vaccine management practices, and the level of community engagement.

The successful stopping of this outbreak reflects the unwavering commitment and collaborative efforts of African governments, health workers, communities and Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) partners, including Rotarians on the ground. Through robust surveillance, quality vaccination campaigns and enhanced community engagement, both countries have effectively controlled the spread of the virus, safeguarding the health and well-being of their children.

“This achievement is a testament to what can be accomplished when we work together with dedication and determination,” said Dr Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa. “I commend the governments of Malawi and Mozambique, as well as all those involved in the response, for their tireless efforts to contain the outbreak. It is now imperative that we continue to strengthen our immunization systems, enhance surveillance, and reach every child with life-saving vaccines.”

Health authorities, with high-quality technical support from GPEI, have put in place national prevention strategies in Malawi and Mozambique, as well as in all districts bordering other countries involved in the response. These include Tanzania, Zimbabwe and Zambia.

To date, more than 100 million vaccine doses have been administered in the most at-risk areas. The strategy to get ahead of this outbreak and stop it before it got out of hand relied on detailed micro-planning, including mapping of cross-border communities, migratory routes, cross-border entry/exit points, and transit routes for each of the cross-border facilities. Synchronization and coordination of vaccination plans across five countries, as well as the monitoring of vaccination activities, proved key to identifying and reaching all eligible children in the cross-border areas, to avoid the risk of paralysis due to the virus.

“The official closure of the outbreak is truly a success due to unfaltering determination and strong collaboration between the governments of Mozambique, Malawi and neighbouring countries, as well as between all partners and health workers. I want to particularly recognise the strong efforts of the vaccination teams working on the frontline to reach every last child,” said Etleva Kadilli, UNICEF Regional Director for Eastern and Southern Africa. “Going forward, routine immunisation must remain high up the priority list; no child is safe from polio until all children are vaccinated.”

To enhance polio surveillance, over the past two years, 15 new wastewater surveillance sites were established in the affected countries. These sites have a critical role to play in detecting silent circulating poliovirus in wastewater, ensuring that quality samples are sent to laboratories for timely confirmation and response to poliovirus presence.

Additionally, countries have scaled up efforts to protect children in high-risk areas by strengthening surveillance, and data and information management. World Health Organization (WHO) in the African Region’s Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Centre has analysed spatial and geographic data on visual maps, providing geographic real-time coverage information, including locating missing settlements, to improve vaccination coverage.

“Closing polio outbreaks is possible when national governments, local health workers, community mobilizers, and global partners come together to prioritize a rapid and timely response to protect children from this devastating disease,” said Dr. Chris Elias, president of Global Development at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “Malawi, Mozambique, and the entire Southern-African region are setting the example for what it takes to urgently improve vaccination campaigns and disease surveillance systems. Commitments like these will help us achieve a world free of all forms of poliovirus.”

Health experts, the OBRA team and GPEI coordinators on the ground underscored the pivotal role of enhanced polio surveillance, high quality community engagement in vaccination campaigns and timely outbreak response, including rapid deployment of experts and other field responders, to curb the virus.

Note to editors:

The notification of imported wild poliovirus in 2022 did not alter the certification of the African region as free of indigenous wild polio in August 2020, as the strain that was confirmed in southern Africa was imported.

Polio has no cure and can cause irreversible paralysis. However, the disease can be prevented and eradicated through administration of a safe, simple and effective vaccine.

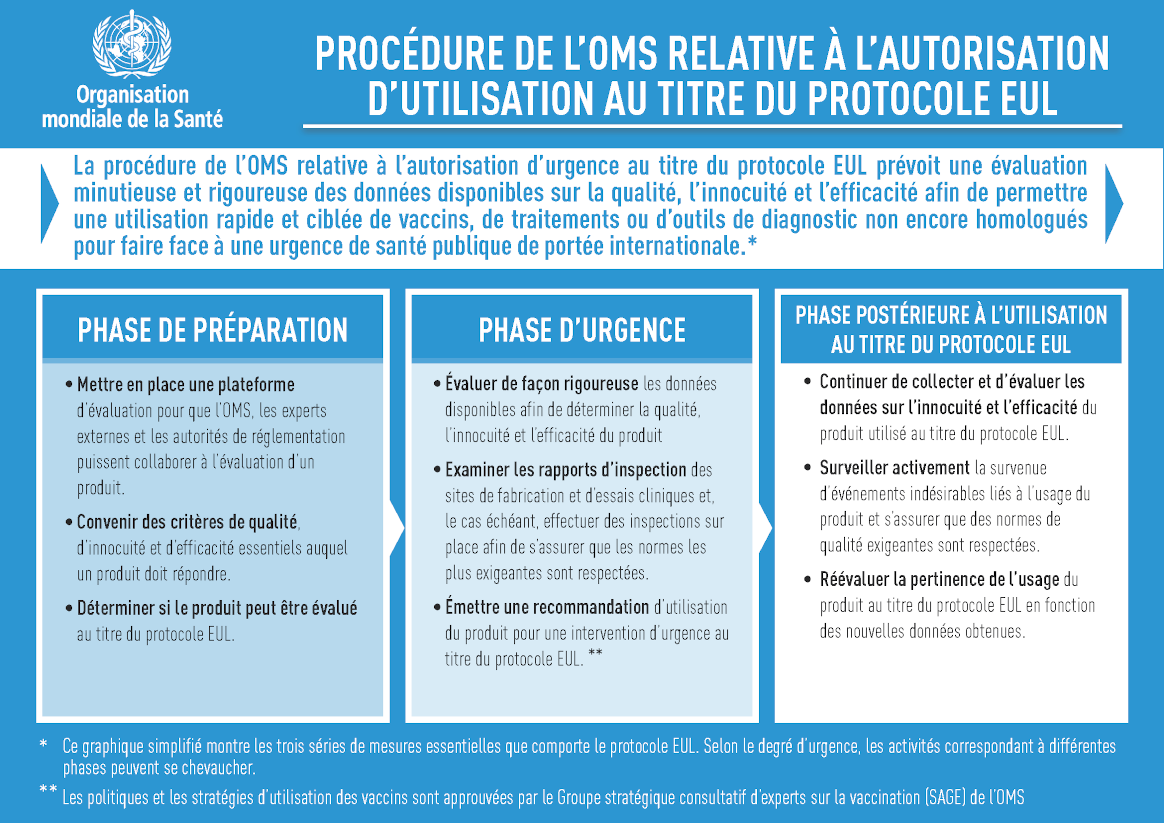

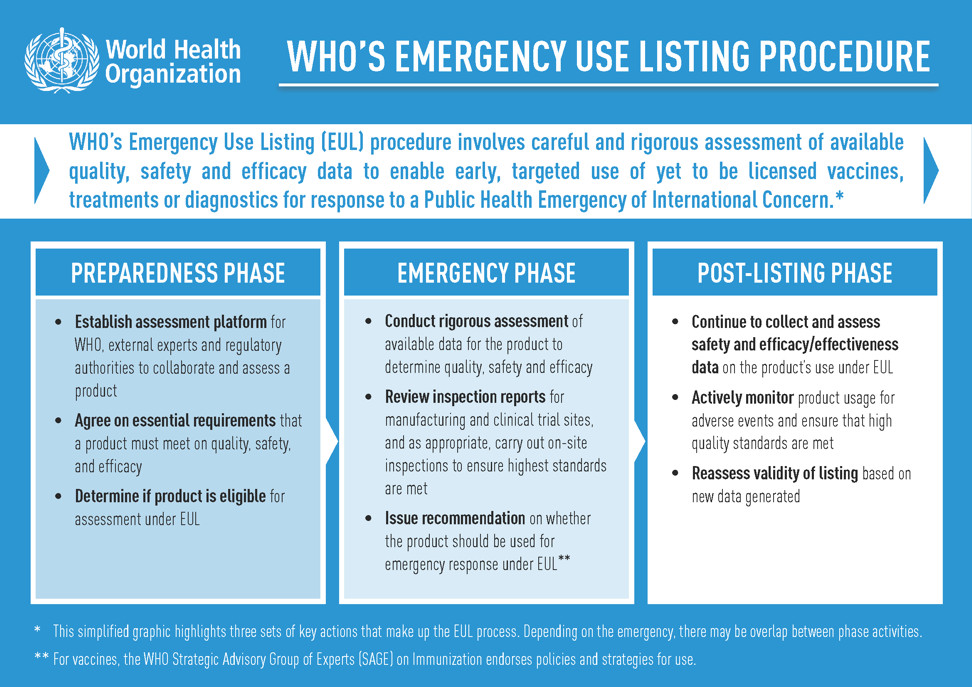

As per the advice of an Emergency Committee convened under the International Health Regulations (2005), the risk of international spread of poliovirus remains a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). Countries affected by poliovirus transmission are subject to Temporary Recommendations. To comply with the Temporary Recommendations issued under the PHEIC, any country infected by poliovirus should declare the outbreak as a national public health emergency, ensure the vaccination of residents and long-term visitors and restrict at the point of departure travel of individuals, who have not been vaccinated or cannot prove the vaccination status.

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative is spearheaded by national governments, WHO, Rotary International, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), UNICEF, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Since 1988, the incidence of wild poliovirus has been reduced by more than 99%, from more 350,000 annual cases in more than 125 endemic countries, to four cases in 2024 from two endemic countries (Pakistan and Afghanistan). In 2023, only 12 cases of WPV1 were detected globally.