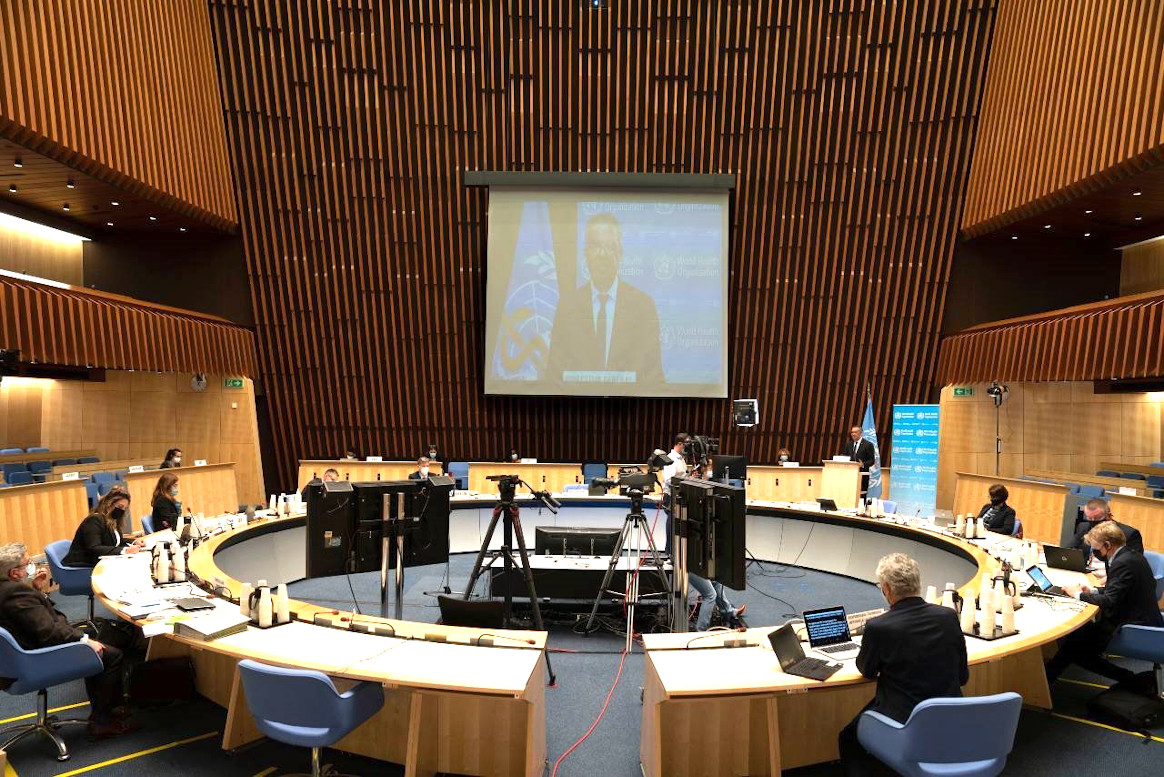

On June 10 2021, the GPEI held a virtual event to launch the new strategy. Here is a recording of the event. The video is also available with subtitles in: French | Arabic |

News Category: Financing and donors

The Heads of State of the G7 countries, at the annual meeting held in the UK on 11-13 June 2021, highlighted the need for increased global efforts to detect global public health threats, by building international surveillance on existing networks such as polio surveillance. In the context of COVID-19, and in their official communiqué, the G7 stated: “we support the establishment… of a global pandemic radar… that builds on existing detection systems such as the influenza and polio programmes.”

The unique value of the polio infrastructure in supporting COVID-19 response efforts was recently underscored by other global fora, including the World Health Assembly in May, and the G7 health ministers meeting in June.

An integral part of the new GPEI Strategy 2022-2026 is to ensure close coordination with broader public health efforts, to not only achieve a lasting world free of all polioviruses, but also one where the polio infrastructure will continue to benefit other public health emergencies long after the disease has been eradicated.

Key to success, however, will be the continued support and engagement of the international development community, including by ensuring that previous pledges are fully and rapidly operationalized.

The health ministers of the G7 countries reaffirmed their commitment to polio eradication, at their annual meeting held in Oxford, UK and virtually, on 3-4 June 2021. As part of their official communique, the health ministers affirmed: “We need to continue supporting the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, whose surveillance capacity and ability to reach vulnerable communities are critical in many countries to prevent and respond to pandemics.”

The statement was welcomed by the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) core partners, which comes ahead of the launch of the new GPEI Strategy 2022-2026, developed in close collaboration with partners, countries and donors, and which lays out the roadmap to achieving and sustaining a world free of all polioviruses. At the same time, the new plan will ensure that the benefits of the polio eradication infrastructure will be able to continue to benefit broader public health efforts long after the disease is gone. In 2020 and 2021, for example, the GPEI infrastructure continues to provide crucial support to the COVID-19 pandemic response, and will continue to do so, as global response continues to accelerate vaccine roll-out efforts. The G7 has recognized that the GPEI has one of the most effective disease surveillance and response networks in the world at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic continues its devastation. It has the ability to respond to not only polio but also other disease outbreaks, contributing to larger global health systems and security.

Key to success, however, will be the continued support and engagement of the international development community, including by ensuring that previous pledges are fully and rapidly operationalized.

GENEVA, 10 June 2021 – Today, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) will launch the Polio Eradication Strategy 2022-2026: Delivering on a Promise at a virtual event, to overcome the remaining challenges to ending polio, including setbacks caused by COVID-19. While polio cases have fallen 99.9% since 1988, polio remains a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and persistent barriers to reaching every child with polio vaccines and the pandemic have contributed to an increase in polio cases. Last year, 1226 cases of all forms of polio were recorded compared to 138 in 2018.

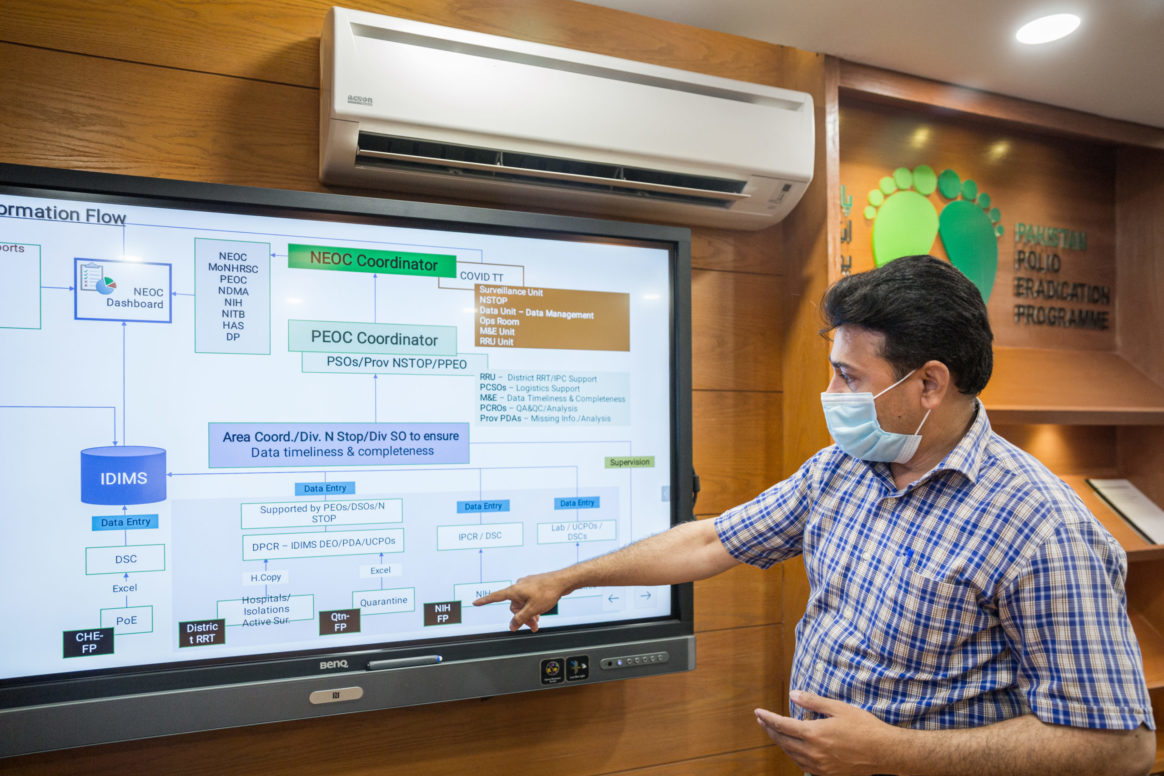

In 2020, the GPEI paused polio door-to-door campaigns for four months to protect communities from the spread of COVID-19 and contributed up to 30,000 programme staff and over $100 million in polio resources to support pandemic response in almost 50 countries.

Leaders from the two countries yet to interrupt wild polio transmission—Pakistan and Afghanistan—called for renewed global solidarity and the continued resources necessary to eradicate this vaccine-preventable disease. They committed to strengthening their partnership with GPEI to improve vaccination campaigns and engagement with communities at high risk of polio.

Dr Faisal Sultan, Special Assistant to the Prime Minister of Pakistan on Health, said, “We are already hard at work with our GPEI partners to address the final barriers to ending polio in Pakistan, particularly through strengthening vaccination campaigns and our engagement with high-risk communities. Eradication remains a top health priority and Pakistan is committed to fully implementing the new GPEI strategy. We look forward to working with international partners to achieve a polio-free world.”

The 2022-2026 Strategy underscores the urgency of getting eradication efforts back on track and offers a comprehensive set of actions that will position the GPEI to achieve a polio-free world. These actions, many of which are underway in 2021, include:

- further integrating polio activities with essential health services—including routine immunization—and building closer partnerships with high-risk communities to co-design immunization events and better meet their health needs, particularly in Pakistan and Afghanistan;

- applying a gender equality lens to the implementation of programme activities, recognizing the importance of female workers to build community trust and improve vaccine acceptance;

- strengthening advocacy to urge greater accountability and ownership of the program at all levels, including enhanced performance measurement and engagement with new partners, such as the new Eastern Mediterranean Regional Subcommittee on Polio Eradication and Outbreaks; and,

- implementing innovative new tools, such as digital payments to frontline health workers, to further improve the impact and efficiency of polio campaigns.

“With this new Strategy, the GPEI has clearly outlined how to overcome the final barriers to securing a polio-free world and improve the health and wellbeing of communities for generations to come,” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization and member of the Polio Oversight Board. “But to succeed, we urgently need renewed political and financial commitments from governments and donors. Polio eradication is at a pivotal moment. It is important we capitalise on the momentum of the new Strategy and make history together by ending this disease.”

Dr Wahid Majrooh, Acting Minister of Public Health for Afghanistan, said, “Afghanistan is fully committed to implementing the new GPEI strategic plan and eradicating polio from its borders. Together we have come so far. Let us take this final step together and make the dream of a polio-free world a reality.”

In addition to eradicating wild polio, GPEI will strengthen efforts to stop outbreaks of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) that continue to spread in under-immunized communities across Africa and Asia. This includes deploying proven tactics used against wild polio, improving outbreak response and streamlining management through the launch of new global and regional rapid response teams and broadening the use of a promising new tool – novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2) – to combat type 2 cVDPVs, the most prominent variant.

H.E. Félix Tshisekedi, President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, said “As Chair of the African Union, I call on every government to increase their commitment to protecting the gains of our monumental efforts and finishing the job against polio in Africa. Only then, we will be able to say we delivered on our promise of a safer, healthier future for all our children.”

Select countries began using nOPV2 in March of this year after WHO issued an Emergency Use Listing recommendation for the vaccine last November. Clinical trials have shown that nOPV2 is safe and effective against type 2 polio, while having the potential to stop cVDPV2 outbreaks in a more sustainable way compared to the existing type 2 oral polio vaccine.

In addition to supporting the COVID-19 response, polio assets and infrastructure have historically helped tackle the emergence of health crises in several countries around the world, including the Ebola outbreak in Nigeria in 2014. Without the support needed for the new GPEI Strategy, there is a risk not only that polio could resurge, but also that countries will be more vulnerable to future health threats.

Additional quotes:

Henrietta Fore, Executive Director, UNICEF: “We will not allow the fight against one deadly disease to cause us to lose ground in the fight against polio and other childhood diseases. Renewed government and donor support will enable us to reach and immunize over 400 million children against polio every year and ensure that no family has to live with the fear of their child being paralyzed by this deadly disease ever again.”

Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, MPH, Director, CDC: “As the GPEI’s support for the COVID-19 response shows, polio infrastructure is vital to helping countries tackle emerging health threats. The U.S. CDC is committed to achieving polio eradication and delivering, through the GPEI’s new strategy, on the promise we made to protect the world’s children. To improve health equity, we must ensure that polio assets are secured and that countries are increasing their immunization coverage through integrated service delivery and demand for vaccines.”

Seth Berkley, CEO, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance: “Polio eradication is possible and essential. Through the increased integration of polio activities with essential immunization and health services, including our joint work to extend the health system to reach “zero-dose” children and missed communities with all routine vaccines, we believe that we can better meet the needs of high-risk communities and secure a polio-free world together.”

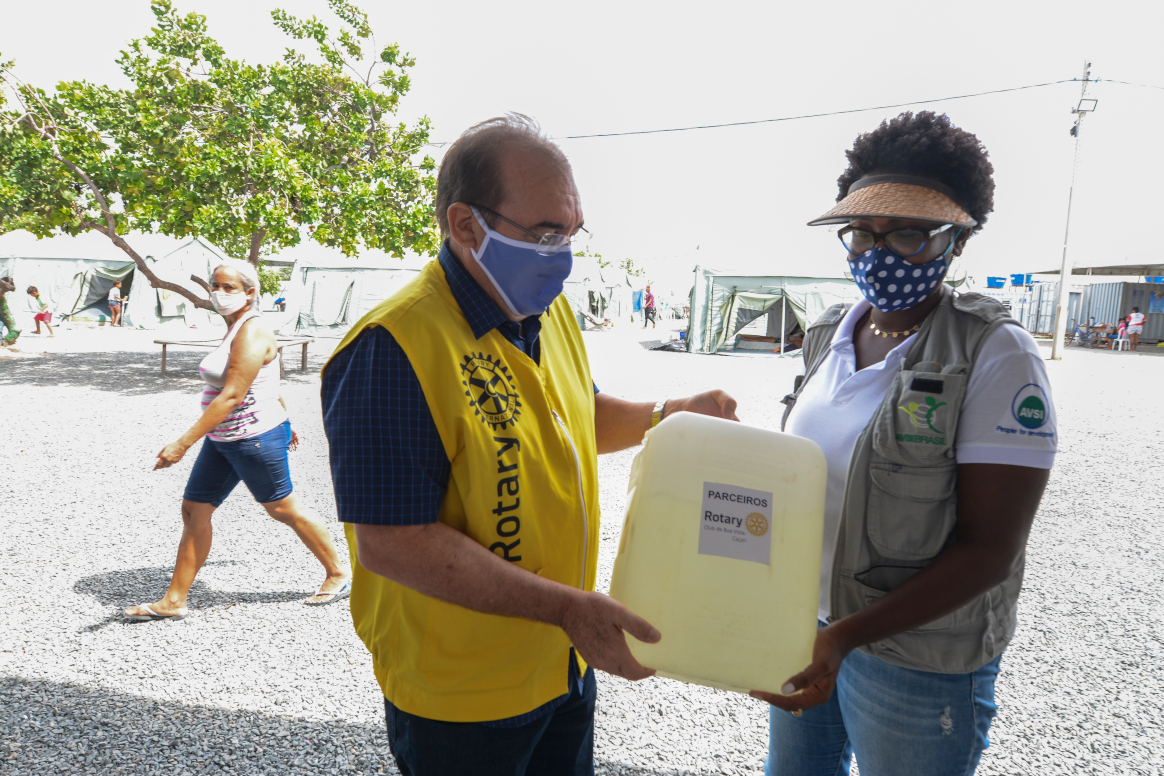

Mike McGovern, Chair, Rotary’s International PolioPlus Committee: “More than 19 million people are walking today who would have otherwise been paralysed by polio, thanks to the incredible progress we’ve made in protecting children with polio vaccines since 1988. When Rotary helped found the GPEI, we made a commitment to ensure that no child or family should live in fear of polio ever again. We are committed to delivering on this promise and urge governments and donors to help us achieve a polio-free world.”

Chris Elias, President, Global Development, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: “After setbacks in recent years, and indications that some donors may reduce funding to the GPEI, there has never been a more important moment than right now in the history of polio eradication. With adequate support for the new strategy, we can secure a world where no child will be paralyzed by polio ever again and we urge all donors to stay committed and consign this disease to history.”

Media contacts:

Oliver Rosenbauer

Communications Officer, World Health Organization

Email: rosenbauero@who.int

Tel: +41 79 500 6536

Ben Winkel,

Communications Manager, Global Health Strategies

Email: bwinkel@globalhealthstrategies.com

Tel: +1 323 382 2290

Note for editors:

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative is a public-private partnership led by national governments with six core partners – the World Health Organization (WHO), Rotary International, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), UNICEF, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

Meeting virtually this week at the 74th World Health Assembly (WHA), global health leaders and ministers of health noted the new Global Polio Eradication Initiative Strategic Plan 2022-2026 and highlighted the importance of collective action to achieve success.

Member States emphasised the urgency of implementation of the strategic plan and urged the WHO Secretariat and Member States to build on recent advances to keep surveillance high, ensure sustained, improved coverage in campaigns and respond rapidly to outbreaks. Several Members States welcomed the establishment of a new EMRO Ministerial Regional Subcommittee on Polio Eradication and Outbreaks, and roll-out of the novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2) to more effectively and sustainably address outbreaks of circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPVs). The Minister of Health of Egypt, Dr Hala Zaid, as a Co-Chair of the Regional Sub-Committee said: “The Regional Subcommittee offers a new, ministerial-level channel to galvanize political support, leverage funding, particularly domestic funding, and raise the profile of polio as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. Its establishment reflects the firm commitment of the Eastern Mediterranean Region to do whatever it takes to stamp out poliovirus transmission and achieve eradication.”

Dr Ahmed Al-Mandhari, the Regional Director for the Eastern Mediterranean, addressed the delegates and noted a year of hard work across the Region. He emphasised the critical step of establishing the ministerial Sub-Committee to ensure more coordinated support for the remaining wild poliovirus-endemic and polio outbreak-affected countries in the Region. Speaking of the new vaccine, Dr Al-Mandhari said, “We are also at the dawn of what we hope will be a new era in responding to VDPV type-2 outbreaks, with an improved vaccine, the novel oral poliovirus type 2, approved for Emergency Use Listing and soon to be used in the Region.”

Member States noted support for local community, progress on closing outbreaks and welcomed efforts to unite with other initiatives to close gaps in immunization. The WHA paid tribute to female frontline workers and highlighted their role in building community relationships. Amid the new COVID-19 reality, the WHA also expressed deep appreciation for the GPEI’s ongoing support to COVID-19 response. WHO’s Deputy Director-General, Dr Zsuzsanna Jakab, highlighted the value of the polio infrastructure in addressing public health emergences, noting that the polio network has been the first in line of defence for COVID-19 response in many countries, and now providing valuable support to the rollout of Covid-19 vaccines. “It is our chance to retain the polio knowledge and expertise to build back stronger and more robust health systems. If we don’t act now, we will lose this enormous opportunity,” said Dr Jakab.

The Regional Director for the African Region, Dr Matshidiso Moeti, thanked African countries and partners for rapidly restarting and innovating to deliver polio activities after a pause during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially following the successful certification of eradication of wild polioviruses last year in the region. Integrating polio functions into other programmes will be critical to maximising the gains against this disease, she said, and to leveraging the wealth of expertise and experience that has been built.

Rotary International welcomed the new strategy and its priority on integration and extended collaboration with partners, as well as its focus on gender equality. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, highlighted the new strategy’s alignment with the Immunization Agenda 2030 and Gavi’s new 5-year strategy, and shared importance of reaching 0-dose children and missed communities with comprehensive and equitable immunization services.

Aidan O’Leary, WHO Director for Polio Eradication, addressed delegates, saying: “Wild poliovirus transmission is restricted to Afghanistan and Pakistan, and while we have seen a sharp decrease in incidence this year, this is no time for complacency. Gaining and sustaining access to all children in Afghanistan and increasing coverage of missed children in core reservoir areas of Pakistan remain the key challenges, and we must all work together to overcome these to achieve and sustain zero cases. At the same time, we must continue to respond to cVDPV2s. The solutions focus not just on the new nOPV2, but also more timely detection, more timely and higher quality outbreak response and strengthening essential immunization services in zero-dose communities and children, aligned with the IA2030 agenda. The new strategy addresses the broader needs of communities through expanded integration and partnership efforts along six distinct workstreams. Implementation will be strengthened through a more systematic approach to performance, risk management and accountability at all levels.”

The new strategy – Delivering on a Promise – will be officially launched at a virtual event on 10 June 2021. Details about the event are available here.

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) is greatly concerned by the United Kingdom’s proposed cuts to contributions toward polio eradication in 2021. The proposed 95% reduction will result in an enormous setback to the eradication effort at a critical moment.

The UK has a long legacy as a leader in global health and its leadership in polio eradication, including financial contributions to the GPEI, have driven wild poliovirus out of all but two countries in the world. The GPEI values the UK government’s steadfast partnership and shared commitment to eradicating polio, and UK citizens have generously championed the drive to end polio. This has helped bring the world to the cusp of being polio-free, whilst providing an investment in broader public health capacity.

In 2019, the UK government pledged to help vaccinate more than 400 million children a year against polio and to support 20 million health workers and volunteers in this vital work. In addition to their life-saving work to end polio, these health workers have been in the frontline of the fight against COVID-19 and have helped some of the world’s most vulnerable countries protect their citizens. The UK’s ongoing support is needed to ensure that the polio infrastructure can continue supporting COVID-19 response efforts, while also resuming lifesaving immunization services against other deadly childhood diseases. In 2020, the UK government’s contributions ensured that the GPEI could continue to support outbreak response in 25 countries and conduct surveillance in nearly 50, all whilst strengthening health systems. The continuation of such support will not be possible unless replacement funds are identified, and as such, this funding cut will have a potentially devastating impact on the polio eradication program.

The GPEI recognises the challenging economic circumstances faced by the UK government and a host of other countries. Governments worldwide are making critical investments in the health of their citizens, as well as evaluating global commitments. Cutting the UK government’s contributions by 95% will, however, put millions of children at increased risk of diseases such as polio and will weaken the ability of countries to detect and respond to outbreaks of polio and other infectious diseases, including COVID-19. Furthermore, it risks delaying polio eradication and the dismantling of one of the most effective disease surveillance and response networks at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic continues its devastation.

GPEI looks forward to working with the UK and the broader global community to address these urgent issues, which jeopardize the collective investment and progress toward a polio free world. Together we can end polio forever and ensure that polio infrastructure and its assets continue to strengthen preparedness and response and save lives.

Even long before the GPEI was formed, Monaco played a leading role in early initiatives to develop a polio vaccine. In the 1950s, Her Serene Highness Princess Grace was an advocate for the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis in the United States of America, founded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt (himself a polio survivor).

The Foundation became known as the “March of Dimes”, so called because of its far-reaching call for funds to research a cure for polio, which at the time was one of the most serious communicable diseases in the USA. Grants from the NFIP facilitated the work of researchers such as Dr. Jonas Salk, creator of the first successful vaccine against poliovirus. But it also facilitated the work of unsung heroes, such as Dr. Leone Farrell at the University of Toronto’s Connaught Medical Research Laboratories. Farrell devised the “Toronto method” for mass production of vaccines, which made the massive field trials of Salk’s vaccine possible, paving the way for the mass vaccination campaigns which have brought us so far in eradicating polio.

Farrell is one of thousands of women past and present at the forefront of the GPEI. The role of women in polio eradication is supported by Polio Gender Champions, who work to raise the voices of women engaged in the programme, and keep gender equality high on the global public health agenda.

And today, Monaco’s proud tradition of support for gender equality and polio eradication continues, with the announcement that H.E. Ms. Carole Lanteri, Ambassador and Permanent Representative of Monaco to the United Nations Office at Geneva will become the newest Gender Champion for Polio Eradication. The Ambassador, formerly co-chair of the GPEI’s Polio Partners Group, explains the significance of this new role:

“As the Covid-19 pandemic continues to affect our lives, women pay a higher price with regressive effects on gender equality. If gender dynamics are not taken into consideration, polio interventions will not be as effective, with the potential risk of exacerbating existing inequalities. More than ever before we must advocate for a meaningful inclusion of women in decision making processes and adopt policies in health programming to reflect this. Today my commitment to these causes is even stronger thanks to my new role as Gender Champion. Following in the footsteps of Princess Grace and taking forward Monaco’s longstanding commitment to gender equality and polio eradication, I am determined to use my voice to advocate for gender mainstreaming in polio eradication to reach every last child.”

Ambassador Lanteri joins the ranks of other gender champions striving to raise awareness of the role of women in polio eradication and on the importance of addressing gender related barriers to immunization. Their work will be instrumental not only in eradicating polio, but also in creating a legacy for recognizing and empowering the role of women in major public health initiatives.

Therese and Léonie reminded me of this hard truth in a recent visit to a hospital in N’Djaména, Chad. One is a newborn girl and the other is a veteran of the campaign to eradicate a human disease for only the second time in history –polio-.

As a Gender Champion for Polio Eradication, I have committed to supporting the global initiative to eradicate polio and the women who work tirelessly to protect children from lifelong paralysis. During my visit to Chad, I had the honour of giving two drops of life-saving oral polio vaccine to two newborns.

Protected from a disease which once struck millions of children, Therese now has a better chance of a healthy life. Thanks to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) – spearheaded by Rotary International, national governments, the World Health Organization, UNICEF, CDC, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance – she is one of more than 2.5 billion children who have received the oral polio vaccine, as the global polio caseload has been reduced by 99% since 1988.

But as I looked at Therese, I also wished that she would have a better chance not just for health, but also for opportunities to prosper. I thought of a recent WHO report I had read – Delivered by Women, Led by Men – which observed that women make up 70% of the global health workforce but hold only 25% of senior roles – a situation that is no different for the polio program. Would Therese’s future reflect that disparity?

I found both frustration and hope in answer to my question when I listened to Ms. Léonie Ngaordoum, the woman responsible for the campaign which brought the vaccine to Therese.

Léonie is head of vaccine operations for Chad’s immunization programme. It is women like her who have brought us this far in the long fight against polio. It is women like her who have gone the extra mile to keep their countries safe when, in 2020, the polio programme faced unprecedented challenges in the face of a new pandemic- COVID-19.

Her journey to a senior public health position in Chad has been difficult. Driven to remote areas on dangerous roads to oversee vaccination campaigns, she has twice suffered accidents, one of which left her with severe spinal injuries. She has faced gender discrimination, countered vaccine misinformation, convinced vaccine sceptics, and stayed the course despite the severe strain of COVID-19, and struggling for respect and recognition in a male-dominated environment.

Today she has a clear vision to share: “I speak about vaccination as if it were a vocation…the program change needed to achieve polio eradication is to empower enough women.” Léonie’s experience highlights the necessity of increasing senior roles among women in the health workforce and involving them in policy decisions.

Women like her frequently operate in dangerous and conflict-affected areas, putting their own personal safety at risk – all in efforts to protect communities from deadly diseases. Women have a greater level of trust with other women and thus are able to enter households and have interactions with mothers and children necessary to deliver the polio vaccine. And this way they can also provide other services, such as health education, antenatal care, routine immunization, and maternal health.

The knowledge and skills gained by this workforce are already being deployed against COVID-19, in surveillance, contact tracing, and raising public awareness. Indeed, more than 50 percent of the time spent by GPEI health workers is already dedicated to diseases and threats beyond polio. It’s clear that the future of public health is inextricably linked to the status of women. Their heroic actions provide nothing less than a blueprint for the future of disease prevention. The Resolution on “Women, girls and the response to COVID-19”, adopted last year by the UN General Assembly, should play a key role when addressing these challenges and the specific needs of women and girls in conflict situations.

The centrality of women to the success of public health projects has for too long gone unrecognised, and must be formalized. That is why today, on International Women’s Day, we must pay tribute to the tremendous contribution of women like Léonie around the world in protecting their communities from deadly diseases such as polio. But at the same time, thinking of the world in which Therese will come of age, we need to commit to empower every woman and girl. It will not only make for a more just world – but a healthier one too.

Throughout her career as a Resource Mobilization Officer for WHO’s polio eradication programme, Heather Monnet has held onto her vision of a polio-free world. A respected communicator with a deep understanding of the polio programme, she was one of the first in the programme to realize that considering gender is crucial to defeat the poliovirus. Since 2017, she has successfully “led from behind”, supporting the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) to develop a gender strategy and workstream which has become a model for other United Nations programmes, and which is designed to overcome some of the most intractable challenges facing polio eradicators.

Describing her motivation, Heather describes “putting on her gender glasses”. She explains, “We had reached a point where it seemed like we had turned nearly every stone to eradicate polio, and yet we had not defeated the disease. At the same time, the introduction of the sustainable development goals had led to an increasing awareness of gender. I began to think more about how gender affects health and health-seeking behaviors.”

“I was not, and am still not a gender expert, but as Member States began to speak more about this issue, it was increasingly on my radar. Putting on my “gender glasses”, I realized that gender was an unexplored intersection for polio eradication, and it could be transformative for our work.”

The case for considering gender

In polio eradication, areas where gender intersects with health delivery include exploring whether boys and girls are equally as likely to receive the polio vaccine, and if gender norms impact whether mothers are able to take their children to health centres for routine immunization.

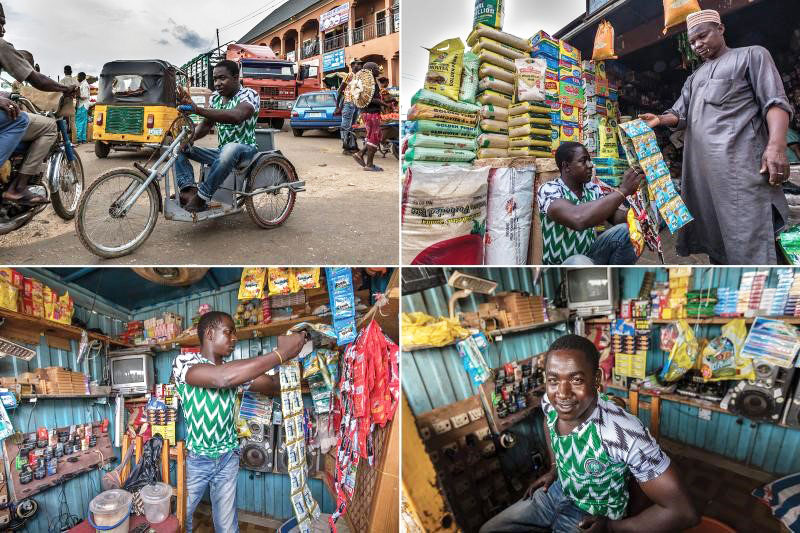

In some places, such as in Nigeria, women are often more effective at delivering the polio vaccine than men, as it is more culturally acceptable for them to interact with mothers and enter homes to vaccinate the smallest children. The GPEI Gender Technical Brief showed how the presence of female health workers in Pakistan has been associated with substantial increases in tetanus vaccine coverage, attended births, and full immunization coverage of children.

To explore and respond to the gender dynamics of polio eradication, the GPEI has published a comprehensive gender equality strategy. A dedicated gender analyst works in the polio programme at WHO headquarters, and gender focal points have been appointed at regional levels and in some country offices. Data is now routinely disaggregated by sex, and there has been a concerted effort to use gender analyses to inform programme policy. The team are currently engaged in implementing the GPEI gender strategy as well as supporting efforts to mainstream gender across WHO, including through a dedicated gender data working group.

Advocating for consideration of gender within the programme has not always been easy. Heather explains, “The polio programme is huge and so many people are involved. Encouraging people to put on their ‘gender glasses’ even for five minutes can be a challenge. But what is really encouraging is that once we educate people about how gender impacts their work, they often have an “aha” moment.”

“The next and crucial steps are striving to ensure that the gender strategy is implemented. This requires all those involved in polio to be engaged – whether it’s designing a gender-inclusive microplan, collecting sex-disaggregated data during a campaign, or considering how gender impacts the way we pay vaccinators. As we integrate gender into our work, we also need to identify the building blocks to ensure that this workstream is sustainably mainstreamed. This is not dependent on one person – rather it takes everyone having exposure.”

Polio Gender Champions

The GPEI gender workstream is supported by Polio Gender Champions, who work to raise the voices of those engaged in the programme. Champions include Senator Hon Marise Payne, Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs and Minister for Women, Wendy Morton, Minister of European Neighbourhood and the Americas at the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office in the United Kingdom, and Arancha González Laya, who is the Spanish Minister for Foreign Affairs, European Union and Cooperation.

Heather explains that the vision and leadership of the gender champions is crucial for achieving change. “The gender champions amplify the voices of those who don’t have a megaphone on the global stage and whose voices need to be heard. For instance, female frontline workers have a lot to say, but their voices aren’t always listened to. Our gender champions raise up these voices from the field.”

“This feeds into our attempts to improve the way that health is delivered. We know that most healthcare is delivered by women, but the systems to deliver it are designed by men. Practical steps to support women employed by the programme may include ensuring that polio vaccination training materials can be understood by individuals with lower literacy, and ensuring that there are safe, private bathrooms available for women to use during long campaign days. When we plan routes to deliver vaccines from house to house, we should consider that women might prefer to take a different route which gives them a greater feeling of personal security. Women may not feel comfortable speaking about these issues to a male supervisor, so we must also ensure that enough female supervisors are recruited and trained. Gender champions are key to keeping these issues high on the global agenda.”

Over the last few years, the GPEI’s gender work has been recognized in multiple high-level forums, and is leading the way for other programmes. Heather identifies two moments when she felt particularly proud – when the Polio Oversight Board adopted and endorsed the GPEI gender strategy, and at a high-level meeting hosted by the Government of the United Arab Emirates in advance of the Reaching the Last Mile Forum in November 2019, during which the Canadian representative described GPEI’s gender strategy as one of the strongest in global health and noted that it should stand as an example for others.

Heather explains, “I have been inspired by what we have achieved – we have planted the seeds and the soil is now being nourished. Our work on gender is growing into something amazing – and the world is watching what it will become.”

PN: President Knaack, thank you for taking the time to speak to us. A little more than a year into the global COVID-19 pandemic, what is your take on the current situation, also with a view of the global effort to eradicate polio?

HK: There are many interesting lessons we learned over the past 12 months. The first is the value of strong health systems, which perhaps in countries like mine – Germany – we have over the past decades taken for granted. But we have seen how important strong health systems are to a functional society, and how fragile that society is if those systems are at risk of collapse. In terms of PolioPlus, of course, the reality is that it is precisely children who live in areas with poor health systems who are most at risk of contracting diseases such as polio. So everything must be done to strengthen health systems systematically, everywhere, to help prevent any disease.

The second lesson is the value of scientific knowledge. COVID-19 is of course a new pathogen affecting the world, and there remain many unanswered questions. How does it really transmit? Who and where are the primary transmittors? How significant and widespread are asymptomatic (meaning undetected) infections and what role do they play in the pandemic? And most importantly, how best to protect our populations, with a minimum impact on everyday life? These are precisely the same questions that were posed about polio in the 1950s. People felt the same fear back then about polio, as we do now about COVID. Polio would indiscriminately hit communities, seemingly without rhyme or reason. Parents would send their children to school in the morning, and they would be stricken by polio later that same day. Lack of knowledge is what is so terrifying about the COVID-19 pandemic. It also means we are to a large degree unable to really target strategies in the most effective way. What polio has shown us is the true value of scientific knowledge. We know how polio transmits, where it is circulating, who is most at risk, and most importantly, we have the tools and the knowledge to protect our populations. This knowledge enables us to target our eradication strategies in the most effective manner, and the result is that the disease has been beaten back over the past few decades to just two endemic countries worldwide. Most recently, Africa was certified as free of all wild polioviruses, a tremendous achievement which could not have been possible without scientific knowledge guiding us. So while we grapple for answers with COVID, for polio eradication, we must now focus entirely on operational implementation. If we optimize implementation, success will follow.

And the third lesson is perhaps the most important: we cannot indefinitely sustain the effort to eradicate polio. We have been on the ‘final stretch’ for several years now. Tantalizingly close to global eradication, but still falling one percent short. In 2020, we saw tremendous disruptions to our operations due to COVID-19. We never know when the next COVID-19 will come along, to again disrupt everything. Last year, the polio program came away with a very serious black eye, so to speak. But we have the opportunity to come back stronger. We must now capitalize on it. We know what we need to do to finish polio. We must now finish the job. We must all recommit and redouble our efforts. If we do that, we will give the world one less infectious disease to worry about once and for all.

PN: You recently called on the Rotary network worldwide to use its experiences from PolioPlus in supporting the COVID-19 response. Could you elaborate on that?

HK: We have a global network of more than 1.2 million volunteers worldwide. This network has been consistently and systematically utilized to help engage everyone from heads of state to mothers in the most remote areas of rural India for polio eradication. We have helped secure vaccine supply and distribution, and increased trust in vaccines among communities. In the process, we have learned many lessons on what it takes to address a public health threat and these same lessons now should be applied to the COVID-19 response, especially as vaccines are now starting to be rolled out. That is why I thought it was important to call on our membership network to use their experiences and apply it to the COVID-19 response.

PN: What has been the reaction so far?

HK: Overwhelmingly supportive, I would say. As an example, in Germany, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Austria and other countries in Europe, Rotarians are encouraging active participation of the provided vaccination service. And because COVID vaccination is provided free of charge, vaccinated individuals are encouraged to instead donate the cost of what this vaccine would have cost them – approximately US$25 – to PolioPlus. This has a dual benefit: they are protected from COVID and contributing to the global response, and they are ensuring children are also protected against polio, critically important now as the COVID-pandemic has significantly disrupted health services and an estimated more than 80 million children worldwide are at increased risk of diseases such as polio.

PN: And from what we understand, the Rotary PolioPlus network of National PolioPlus Committees has in any event been supporting global pandemic response over the past 12 months already, is that correct?

HK: The ‘Plus’ in PolioPlus has always stood for the fact that we are eradicating polio, but doing it in such a way that we are in fact doing much more, by supporting broader public health efforts. I’m extremely proud that Rotary and Rotarians around the world have helped bring the world to the threshold of being wild polio-free. But I’m perhaps even more proud of the ‘plus’ – or ‘added’ value – that this network has provided in the process. Things that are largely unseen, but which are very evident and concrete. So indeed, Rotarians have been actively engaged in the pandemic response, particularly in high-risk areas such as Pakistan, and Nigeria. We have supported contact tracing, educated communities on hygiene and distancing measures, supporting testing and other tactics. We have a unique set of experiences, and more importantly a unique infrastructure and network, to help during such crises. It’s morally the only way to operate. And actually, it is operationally beneficial also to polio eradication, as we are engaging with communities on broader terms, and not just on polio.

PN: Thank you again for taking the time to speak with us. Do you have any final thoughts or reflections for our readers?

HK: If we did not know it before, we certainly know now how quickly and dangerously infectious diseases spread around the globe. Polio is no different, and we know that it will not stay confined to Pakistan and Afghanistan if we don’t stop transmission there as soon as possible. We know that given the chance, this disease will come roaring back, and within ten years, we would again see 200,000 children paralysed every single year, all over the world. Perhaps even in my country, Germany. That would be a humanitarian catastrophe that must be averted at all costs.

The good news is that it can be averted. We know what it takes. Pakistan and Afghanistan are re-launching their national eradication efforts in an intensified, emergency manner, following a disrupted 2020. This is encouraging to see. Mirroring this engagement must be the strengthened commitments by the international development community. We must ensure that the financial resources are urgently mobilised to finish polio once and for all. I am particularly proud that my own government, Germany, for example, has just recently committed an additional 35 million EURO to the effort, along with an additional 10 million EURO for efforts in Nigeria and Pakistan. Such support is particularly critical now, given that more than 80 million children are at heightened risk of diseases such a polio due to COVID-19 disruptions, and late last year, UNICEF and WHO issued an emergency call for action to urgently address this. And as we have seen, by supporting polio eradication, donors effectively get twice as much for their contribution: they help contribute to polio eradication, but also by doing so help contribute to the polio network’s support to public health emergencies such as COVID-19.

In short, we have it in our own hands to achieve success. There are no technical or biological reasons why polio should persist anywhere in the world. It is now a question of political and societal will. If we all redouble our efforts, success will follow.

Please consider making a contribution to Rotary’s PolioPlus fund, and have your donation matched 2-to-1 by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Meeting virtually at this week’s WHO Executive Board (EB), global health leaders and ministers of health urged for concerted and emergency efforts to finally rid the world of polio, noting a global and collective responsibility to finish the disease once and for all. Delegates also reiterated their support for the sustainable transitioning of polio assets, recognizing that successful polio transition and polio eradication are twin goals.

Noting that endemic wild poliovirus is now restricted to just two countries – the lowest number in history – with the African region being certified as wild polio-free in August 2020, delegates urged intensified efforts to wipe out the remaining chains of transmission of this strain and prevent global resurgence. The representatives of both Pakistan and Afghanistan demonstrated strong commitments to this goal and urged collective responsibility to achieve success. Delegates also expressed strong appreciation for the establishment of the Eastern Mediterranean Ministerial Regional Subcommittee on Polio Eradication and Outbreaks, by WHO Regional Director Dr Ahmed Al-Mandhari, which focuses on critical barriers to overcome to achieve zero poliovirus.

The EB urged all stakeholders to follow WHO and UNICEF’s joint emergency call to action, launched 6 November 2020, including by prioritising polio in national budgets as they rebuild their immunization programmes in the wake of COVID-19, and urgently mobilising additional resources for polio emergency outbreak response. To address the increasing global health emergency associated with circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) outbreaks, delegates expressed appreciation of new strategic approaches, including the roll-out of novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2), a next-generation OPV aimed at more effectively and sustainably addressing these outbreaks. This vaccine, which was recently granted a WHO Emergency Use Listing recommendation, is anticipated to be initially rolled-out in the first quarter of 2021. The GPEI is working with countries affected and at high risk of cVDPV2 to prepare for possible use of the vaccine.

Amid the new COVID-19 reality, the EB also expressed deep appreciation for the GPEI’s ongoing support to COVID-19 response. In December 2020, the heads of the GPEI core partners at their final Polio Oversight Board (POB) meeting of the year, confirmed that the polio infrastructure will continue to provide such support, including to the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out.

Member States additionally reiterated their support of polio transition, emphasising the need to ensure sustained, robust public health programming. Several EB members urged for strengthening the links built between the polio, immunization and emergencies programmes during COVID-19 response in the next phase of the pandemic, including for the effective rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Director-General of WHO, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, commented, “We share the understanding that polio eradication and transition are equally important targets: as we work towards eradication we must think about the future. This is how we will ensure that health systems retain capacity and are strengthened long after polio is ended.”

WHO’s Deputy Director-General, Dr Zsuzsanna Jakab, noted the increasing cross-programmatic integration between polio and other public health programmes, including the introduction of integrated public health teams in countries prioritized for polio transition, bringing together polio, emergencies and immunization expertise. The Regional Director for the African Region, Dr Matshidiso Moeti, emphasised that the work of polio personnel to support the pandemic response, “highlight[s]… the importance of working in interconnected ways going forward.” Dr Al-Mandhari, addressing the delegates, said: “Polio continues to be a public health emergency of international concern. Now is the time to be shoring up the polio programme and mobilizing funding, including domestic funds, so that this remarkable public health and pandemic response mechanism can remain robust and can be integrated into broader public health services across the region. Now is the time for full regional solidarity and mobilization.”

Speaking on behalf of children worldwide, Rotary International – the civil society arm of the GPEI partnership – thanked global health leaders for their continued dedication to polio eradication and public health, sentiments echoed by several other partners, including the United Nations Foundation (UNF). UNF expressed concern about the drop in population immunity, especially for polio and measles, declared support for the joint emergency call to action to prioritize investments for preventing and responding to polio and measles outbreaks, and urged continued focus on strengthening immunization programmes.

The EB discussion will also help inform the finalization of the new strategic plan. This strengthened strategic plan – being developed in broad consultation with partners, stakeholders and countries – is based on best practices and lessons learned, and focuses on fully implementing approaches proven to work. It is expected to be presented to the World Health Assembly in May.

“If we did not know it before, we certainly know now how quickly infectious diseases can spread across the world and wild polio is one such infectious disease. Unlike with COVID-19, where many medical and scientific questions remain unanswered, we know precisely what it takes to stop polio,” said Aidan O’Leary, newly-appointed Director of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative at WHO. “We know how polio transmits, who is primarily at risk and we have all the tools and approaches needed to stop it. That is what this strengthened strategic plan is all about – to bring all the solutions together into a single roadmap to achieve success and through focusing on more effective implementation. What discussions at the EB this week clearly displayed is a strong global sense of commitment and solidarity to do just that: better implementation of what we know works. Together, if we do that, success will follow and we will be able to give the world one less infectious disease to worry about, once and for all.”

Speaking more broadly on global public health issues, the EB welcomed confirmation by the United States of its intention to remain a member of WHO. In a statement by the United States, the country underscored WHO’s critical role in the world’s fight against COVID-19 and countless other threats to global health and health security, confirming it would continue to be a full participant and global leader in confronting such threats and advancing global health and health security.

O’Leary took over as Director for Polio Eradication at WHO on 1 January 2021, from Michel Zaffran, who will enter a well-deserved retirement end-February. O’Leary brings with him a vast array of experience in both polio eradication and emergencies, including through the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

PN: Aidan, Michel, thank you both for taking the time to speak with us today. Aidan – you are taking over from Michel as Director for Polio Eradication at WHO. Polio is 99% eradicated globally, but it has been at 99% for many years. Ultimately, your job will be to achieve that elusive 100%. Do you find the task ahead daunting?

A-O’L: I’m not sure ‘daunting’ is the adjective I would use. But ‘challenging’ for sure. As you say, we have been at 99% for many years now. We have reduced the incidence of polio from 350,000 children paralysed every year in 1988, to less than 1,000 in 2020. But that is not enough, not if we are trying to eradicate a disease. Polio is a highly-infectious disease, and if we did not know it before COVID-19, we certainly know now how quickly infectious diseases can spread globally. If we do not eradicate polio, this virus will resurge globally.

PN: As new Director, what will be your priorities?

A-O’L: My priority, and all of our priorities, must be simply this: find and vaccinate every last child. If we do that, poliovirus will have nowhere to hide. That means in the first instance finding out where those last remaining unreached children are, and what obstacles stand in the way to vaccinating them. Is it because of lack of infrastructure? Insecurity or inaccessibility? Lack of proper operational planning? Population movements? Resistance? Gender-related barriers? If we can identify the underlying reasons, we can adapt our operations and really zero in on those last remaining virus strains.

PN: Michel, you have led this effort for the past five years, and during that time have guided the effort to restrict wild poliovirus transmission to just Pakistan and Afghanistan. You have overseen the achievement of a wild polio-free Africa, an incredible achievement. However, this time has also seen an increase in emergence of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus, or cVDPV, outbreaks. How do you see the priorities going forward?

MZ: The goal of this effort is of course to ensure that no child will ever again be paralysed by any poliovirus, be it wild or vaccine-derived. This we have to achieve in phases. First, we have to interrupt all remaining wild poliovirus strains, before we can then ultimately stop use of oral polio vaccine, or OPV for short, in order to eliminate the long-term risks of cVDPVs. Aidan has tremendous experience, in both remaining wild poliovirus endemic countries, having led the OCHA office in Afghanistan and having been Chief of Polio Eradication in Pakistan for UNICEF. So he knows the challenges and realities involved. Eradicating the last remaining strains of wild poliovirus must be the overriding priority – success ultimately hinges on that.

At the same time, we have new strategies, tools and approaches to address the increasing cVDPV emergency, notably the novel OPV type 2, or nOPV2 for short, to more effectively and sustainably stop such strains. Ultimately, though, we need to reach children. Only vaccinations save lives, not vaccines.

A-O’L: Michel just mentioned an important word: emergency. And that is precisely what we are facing with polio, whether it’s wild or vaccine-derived. I believe my experience working in emergency settings can help us achieve our goal, including by linking polio operations more closely to other emergency efforts. That is also one of the reasons why WHO and UNICEF recently jointly issued an emergency call for action on polio and measles, and we hope all stakeholders will respond accordingly.

MZ: I would echo that. Particularly in a post-COVID world, the programme must also continue to adapt its approaches and operations, and no longer work so much in isolation. We have to integrate with other efforts including emergency response and broader routine immunization efforts.

A-O’L: I would just add that Michel is really leaving me with a solid base to operate from. He and his teams across the GPEI partnership have built up such a strong infrastructure. I’m thinking here for example of the gender equality work of the programme – it has really been trail-blazing and I know other health and development efforts are looking to our experience on this. It’s a great opportunity to further leverage and expand collaboration with others. So we’ve really become a global leader in many new ways of working, and ultimately, that can only mean more support for this effort.

PN: Thank you so much for speaking with us today. Could we ask for final thoughts from both of you?

A-O’L: We have many challenges, but if any network can achieve success, it is the GPEI network. Our greatest strength that we have is partnerships. Starting with Rotary International and Rotarians worldwide who are tirelessly working towards success, to our other partners including at my old organization UNICEF and our newest partner Gavi who is helping to integrate the programme, and of course ultimately to donor and country governments and communities: this is where our strength and power lies. If we harness this partnership effectively, if we all work together, then we will reach that last remaining child, and we will ensure that this disease is eradicated once and for all.

MZ: For me it has been an absolute honour and privilege to lead this effort for the past years, and I leave with a sense of real optimism. I believe Aidan is the right person for this job right now. In November, at the World Health Assembly, we saw tremendous support for polio eradication from Member States. We have new tools, such as nOPV2, and tremendous new commitments. We are working on a new strategy, to lead us to success. But ultimately, all comes down now to implementation. 2020, the COVID year, taught us many lessons. Many of the questions that are still being asked about COVID – how does it transmit, where is it primarily circulating, what are the best tools and strategies to stop it – have been answered for polio. We know what the virus is doing, how it is behaving, and who it is affecting. Most importantly, we know what we have to do to stop it, and we have all the tools to stop it. But what 2020 also taught us is that this cannot last forever. We never know when a next COVID emergency comes along, which will disrupt everything. In polio eradication, we are being given another chance in 2021, after a bruising 2020. We have to capitalize on it. We have to focus everything on implementation. If we do that, success will follow.

In a newly-released statement following the final meeting of the Polio Oversight Board (POB) that was held virtually on 18 December 2020, the POB looks back at the support that the programme provided to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, while remaining strongly devoted to the goal of a polio-free world. The POB reaffirms its commitment that polio-funded assets are available to countries to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in the next phase of COVID-19 vaccine introduction and delivery.

The POB also believes that for countries introducing COVID-19 vaccine, there are lessons and experiences to be learnt from the rollout of nOPV2 under the EUL recommendation, if emergency regulatory pathways such as WHO EUL are used, including in the areas of monitoring readiness-verification, safety surveillance, and regulatory considerations.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the need for strong health systems and global health security into sharp focus. Last week, the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) agreed a £30 million increase in the first payment to the World Health Organization of their 2019 – 2023 pledge, meaning that the total amount released for polio eradication activities is £70 million. Coming amidst challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, including a growing immunity gap, this gesture is a testament to the UK government’s strong commitment to investing in high impact programmes that strengthen global health security – including the polio programme.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) has played an integral role in the global response, contributing physical assets, outbreak response expertise and a trained workforce to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus. This support was largely made possible thank to donors like the United Kingdom.

The United Kingdom is a historic donor to efforts to end polio, committing an exceptional £400 million to eradication activities in the period from 2019 – 2023. Since 1985, the UK has contributed over US $1.6 billion, and has played an integral role in preventing the paralysis of more than 18 million children.

Widespread polio vaccination efforts over the past 30 years have led to a 99.9% decrease in global polio cases. Health workers, local governments, global partners and generous donors have made this progress possible. The increased payment by the UK will ensure that this progress against polio is not lost due to disruptions by the COVID-19 pandemic, and that the polio programme can continue to play an essential role in supporting pandemic response efforts around the world.

As the U.K. prepares to host the upcoming G7 meeting, the GPEI is hopeful that issues around global health security and health systems strengthening, to which polio can contribute, will be prioritized.

Mr Aidan O’Leary has been officially appointed as the new Director for Polio Eradication at the World Health Organization, with effect from 1 January 2021. O’Leary is taking over from Michel Zaffran, who will enter retirement end-February.

O’Leary brings with him a wealth of emergencies and public health experience. Originally from Ireland, he is currently Head of Office in Yemen for the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), in addition to having extensive experience in emergency settings such as Iraq and Syria, where he also served as Head of Office for OCHA.

O’Leary also has strong experience of working on polio eradication in the remaining wild poliovirus endemic countries. He was Chief of Polio Eradication in Pakistan for UNICEF from 2015-2017 and Head of Office for OCHA in Afghanistan from 2011-2014.

“I’m excited to join this incredible programme,” commented O’Leary on his appointment. “COVID-19 led to a tough year for polio eradication in 2020, but we have adapted our strategies and I believe this programme has a real opportunity to reboost our efforts in 2021. I’ve been so impressed by how this programme has taken on challenges and continues to innovate, and all of it rooted in its strong partnership. I look forward to working with all partners, including my old organization UNICEF, and of course Rotarians from around the world.”

“With this appointment, I am able to enter my retirement with a sense of reassurance,” said Michel Zaffran. “He is the right person for the job at this time, given his set of experiences both in the polio programme and emergencies, and in particular in Pakistan and Afghanistan. I am confident his leadership will help drive this programme to ultimate success.”

O’Leary joins the GPEI in 2021, and will focus on capitalizing on new commitments displayed at the World Health Assembly in November, the introduction of new tools and innovations such as novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2), and an optimization of new governance and strategy structures currently being developed across the partnership.

The GPEI welcomes Aidan O’Leary to the GPEI family.

In a year marked by the global COVID-19 pandemic, global health leaders convening virtually at this week’s World Health Assembly called for continued urgent action on polio eradication. The Assembly congratulated the African region on reaching the public health milestone of certification as wild polio free, but highlighted the importance of global solidarity to achieve the goal of global eradication and certification.

Member States, including from polio-affected and high-risk countries, underscored the damage COVID-19 has caused to immunization systems around the world, leaving children at much more risk of preventable diseases such as polio. Delegates urged all stakeholders to follow WHO and UNICEF’s joint call for emergency action launched on 6 November to prioritise polio in national budgets as they rebuild their immunization systems in the wake of COVID-19, and the need to urgently mobilise an additional US$ 400 million for polio for emergency outbreak response over the next 14 months. In particular, Turkey and Vietnam have already responded to the call, mobilising additional resources and commitments to the effort.

The Assembly expressed appreciation at the GPEI’s ongoing and strategic efforts to maintain the programme amidst the ‘new reality’, in particular the support the polio infrastructure provides to COVID-19-response efforts. Many interventions underscored the critical role that polio staff and assets play in public health globally and underline the urgency of integrating these assets into the wider public health infrastructure.

At the same time, the GPEI’s work on gender was recognized, with thanks to the Foreign Ministers of Australia, Spain and the UK for their roles as Gender Champions for polio eradication.

Delegates expressed concern at the increase in circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) outbreaks, and urged rapid roll-out of novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2), a next-generation oral polio vaccine aimed at more effectively and sustainably addressing these outbreaks. This vaccine is anticipated to be initially rolled-out by January 2021.

Speaking on behalf of children worldwide, Rotary International – the civil society arm of the GPEI partnership – thanked the global health leaders for their continued dedication to polio eradication and public health, and appealed for intensified global action to address immunization coverage gaps, by prioritizing investment in robust immunization systems to prevent deadly and debilitating diseases such as polio and measles.

Related resources

GENEVA/ NEW YORK, 6 November 2020 – UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO) today issued an urgent call to action to avert major measles and polio epidemics as COVID-19 continues to disrupt immunization services worldwide, leaving millions of vulnerable children at heightened risk of preventable childhood diseases.

The two organizations estimate that US$655 million (US$400 million for polio and US$255 million for measles) are needed to address dangerous immunity gaps in non-Gavi eligible countries and target age groups.

“COVID-19 has had a devastating effect on health services and in particular immunization services, worldwide,” commented Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General. “But unlike with COVID, we have the tools and knowledge to stop diseases such as polio and measles. What we need are the resources and commitments to put these tools and knowledge into action. If we do that, children’s lives will be saved.”

“We cannot allow the fight against one deadly disease to cause us to lose ground in the fight against other diseases,” said Henrietta Fore, UNICEF Executive Director. “Addressing the global COVID-19 pandemic is critical. However, other deadly diseases also threaten the lives of millions of children in some of the poorest areas of the world. That is why today we are urgently calling for global action from country leaders, donors and partners. We need additional financial resources to safely resume vaccination campaigns and prioritize immunization systems that are critical to protect children and avert other epidemics besides COVID-19.”

In recent years, there has been a global resurgence of measles with ongoing outbreaks in all parts of the world. Vaccination coverage gaps have been further exacerbated in 2020 by COVID-19. In 2019, measles climbed to the highest number of new infections in more than two decades. Annual measles mortality data for 2019 to be released next week will show the continued negative toll that sustained outbreaks are having in many countries around the world.

At the same time, poliovirus transmission is expected to increase in Pakistan and Afghanistan and in many under-immunized areas of Africa. Failure to eradicate polio now would lead to global resurgence of the disease, resulting in as many as 200,000 new cases annually, within 10 years.

New tools, including a next-generation novel oral polio vaccine and the forthcoming Measles Outbreak Strategic Response Plan are expected to be deployed over the coming months to help tackle these growing threats in a more effective and sustainable manner, and ultimately save lives. The Plan is a worldwide strategy to quickly and effectively prevent, detect and respond to measles outbreaks.

Notes to editors:

Download photos and broll on vaccinations, including polio and measles vaccinations here

Generous support from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, has enabled previous access to funding for outbreak response, preventive campaigns and routine immunization strengthening, including additional support for catch-up vaccination for children who were missed due to COVID-19 disruptions in Gavi-eligible countries. However, significant financing gaps remain in middle-income countries which are not Gavi-eligible. This call for emergency action will go to support those middle-income countries that are not eligible for support from Gavi.

About UNICEF

UNICEF works in some of the world’s toughest places, to reach the world’s most disadvantaged children. Across 190 countries and territories, we work for every child, everywhere, to build a better world for everyone. For more information about UNICEF and its work for children, visit www.unicef.org. For more information about COVID-19, visit www.unicef.org/coronavirus. To know more about UNICEF’s work on immunization, visit https://www.unicef.org/immunization

Follow UNICEF on Twitter and Facebook

About the Global Polio Eradication Initiative

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative is spearheaded by WHO, Rotary International, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), UNICEF, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

About the Measles & Rubella Initiative

The Measles & Rubella Initiative (M&RI) is a partnership between the American Red Cross, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), UNICEF, the United Nations Foundation and the World Health Organization. Working with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and other stakeholders, the Initiative is committed to achieving and maintaining a world without measles, rubella and congenital rubella syndrome. Since 2000, M&RI has helped deliver over 5.5 billion doses of measles vaccine to children worldwide and saved over 23 million lives by increasing vaccination coverage, responding to outbreaks, monitoring and evaluation, and supporting demand for vaccine.

Related resources

Rotary’s 2020 World Polio Day Online Global Update programme on 24 October hails this year’s historic achievement in polio eradication: Africa being declared free of the wild poliovirus.

Paralympic medalist and TV presenter Ade Adepitan, who co-hosts this year’s programme, says that the eradication of wild polio in Africa was personal for him. “Since I was born in Nigeria, this achievement is close to my heart,” says Adepitan, a polio survivor who contracted the disease as a child. “I’ve been waiting for this day since I was young.”

He notes that, just a decade ago, three-quarters of all of the world’s polio cases caused by the wild virus were contracted in Africa. Now, more than a billion Africans are safe from the disease. “But we’re not done,” Adepitan cautions. “We’re in pursuit of an even greater triumph — a world without polio. And I can’t wait.”

Rotary Foundation Trustee Geeta Manek, who co-hosts the programme with Adepitan, says that World Polio Day is an opportunity for Rotary members to be motivated to “continue this fight.”

She adds, “Rotarians around the world are working tirelessly to support the global effort to end polio.”

Now that the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared that its African region is free of the wild poliovirus, five of the WHO’s six regions, representing more than 90 percent of the world’s population, are now free of the disease. It is still endemic in Afghanistan and Pakistan, both in the WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean region.

“This effort required incredible coordination and cooperation between governments, UN agencies, civil organizations, health workers, and parents,” says Manek, a member of the Rotary Club of Muthaiga, Kenya. “I’m proud of what we’ve accomplished.”

A collective effort

Dr. Tunji Funsho, chair of Rotary’s Nigeria PolioPlus Committee and a member of the Rotary Club of Lekki Phase 1, Lagos State, Nigeria, tells online viewers that the milestone couldn’t have been reached without the efforts of Rotary members and leaders in Africa and around the world.

Funsho, who was recently named one of TIME magazine’s 100 Most Influential People of 2020, says countless Rotarians helped by holding events to raise awareness and to raise funds or by working with governments to secure funding and other support for polio eradication.

“Polio eradication is truly a collective effort … This accomplishment belongs to all of us,” says Funsho.

Rotary and its members have contributed nearly $890 million toward polio eradication efforts in the African region. The funds have allowed Rotary to award PolioPlus grants to fund polio surveillance, transportation, awareness campaigns, and National Immunization Days.

This year’s World Polio Day Online Global Update is streamed on Facebook in several languages and in a number of time zones around the world. The programme, which is sponsored by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, features Jeffrey Kluger, editor at large for TIME magazine; Mark Wright, TV news host and member of the Rotary Club of Seattle, Washington, USA; and Angélique Kidjo, a Grammy Award-winning singer who performs her song “M’Baamba.”

The challenges of 2020

It’s impossible to talk about 2020 without mentioning the coronavirus pandemic, which has killed more than a million people and devastated economies around the world.

In the programme, a panel of global health experts from Rotary’s partners in the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) discuss how the infrastructure that Rotary and the GPEI have built to eradicate polio has helped communities tackle needs caused by the COVID-19 pandemic too.

“The infrastructure we built through polio in terms of how to engage communities, how to work with communities, how to rapidly teach communities to actually deliver health interventions, do disease surveillance, et cetera, has been an extremely important part of the effort to tackle so many other diseases,” says Dr. Bruce Aylward, Senior Adviser to the Director General at the WHO.

Panelists also include Dr. Christopher Elias, President of the Global Development Division of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Henrietta H. Fore, Executive Director of UNICEF; and Rebecca Martin, Director of the Center for Global Health at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Elias says that when there are global health emergencies, such as outbreaks of other contagious diseases, Rotarians always help. “They take whatever they’ve learned from doing successful polio campaigns that have reached all the children in the village, and they apply that to reaching them with yellow fever or measles vaccine.”

The programme discusses several pandemic response tactics that rely on polio eradication infrastructure: Polio surveillance teams in Ethiopia are reporting COVID-19 cases, and emergency operation centers in Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan that are usually used to fight polio are now also being used as coordination centers for COVID-19 response.

The online programme also includes a video of brave volunteer health workers immunizing children in the restive state of Borno, Nigeria, and profiles a community mobilizer in Afghanistan who works tirelessly to ensure that children are protected from polio.

Kluger speaks with several people, including three Rotary members, about their childhood experiences as “Polio Pioneers” — they were among more than a million children who took part in a huge trial of Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine in the 1950s.

The future of the fight against polio

Rotary’s challenge now is to eradicate the wild poliovirus in the two countries where the disease has never been stopped: Afghanistan and Pakistan. Routine immunizations must also be strengthened in Africa to keep the virus from returning there. The polio partnership is working to rid the world of all strains of poliovirus, so that no child is affected by polio paralysis ever again.

To eradicate polio, multiple high-quality immunization campaigns must be carried out each year in polio-affected and high-risk countries. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it is necessary to maintain populations’ immunity against polio while also protecting health workers from the coronavirus and making sure they don’t transmit it.

Rotary has contributed more than $2.1 billion to polio eradication since it launched the PolioPlus programme in 1985, and it’s committed to raising $50 million each year for polio eradication activities. Because of a 2-to-1 matching agreement with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, each year, $150 million goes toward fulfilling Rotary’s promise to the children of the world: No child will ever again suffer the devastating effects of polio.

Consider making a donation to Rotary’s PolioPlus Fund in honor of World Polio Day.

Dr. Tunji Funsho, chair of Rotary’s Nigeria National PolioPlus Committee, joins 100 pioneers, artists, leaders, icons, and titans as one of TIME’s 100 Most Influential People. TIME announced its 2020 honorees during a 22 September television broadcast on ABC, recognizing Funsho for his instrumental leadership and work with Rotary members and partners to achieve the eradication of wild polio in the African region.

He is the first Rotary member to receive this honor for work toward eradicating polio.

A Rotarian for 35 years, Funsho is a member of the Rotary Club of Lekki, Nigeria, past governor of District 9110, and serves on Rotary’s International PolioPlus Committee. Funsho is a cardiologist and a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of London. He lives in Lagos, Nigeria with his wife Aisha. They have four children; Habeeb, Kike, Abdullahi and Fatima; and five grandchildren.

TIME 100 comprises individuals whose leadership, talent, discoveries, and philanthropy have made a difference in the world. Past honorees include Bono, the Dalai Lama, Bill Gates, Nelson Mandela, Angela Merkel, Oprah Winfrey, and Malala Yousafzai.

The WHO African Region is expected to be certified free of wild poliovirus on 25 August 2020. Chair of the WHO’s International Health Regulations Emergency Committee and of the AFRO Regional Immunization Technical Advisory Group Helen Rees explains the current cVDPV situation in Africa and its implications ahead of regional wild polio-free certification.

Q. Fifteen countries (as of 14 August 2020) in the World Health Organization’s African region have reported cases of circulating vaccine-derived polio type 2 (cVDPV2) in 2020. The total number of outbreak countries is 16. How does that impact the region’s upcoming wild polio-free certification?

First, it’s important to clarify that cVDPV is a different virus from the wild poliovirus, and will undergo a separate process to validate its absence once wild polio has been eradicated globally.

Second, I want to underscore that the ongoing cVDPV2 outbreaks in Africa do not affect the programme’s confidence that wild polio is gone from the region. Certification is backed by extensive data and a thorough evaluation process that demonstrates wild polio transmission has been interrupted on the continent.

In Africa, an independent body of experts called the African Regional Certification Commission for polio eradication (ARCC) oversees this process by carefully reviewing country documentation and analyzing the quality of surveillance systems and immunization coverage. With this intensive monitoring of polio programmes across the continent, the ARCC is able to confirm with 100% certainty that wild polio is gone from the region.

But for the ARCC, national polio programmes and GPEI partners, the work does not end here. Stopping cVDPVs remains an urgent priority. African countries will need to strengthen their efforts to reach all children with polio vaccines to protect them from cVDPVs and any importation of wild polio from the remaining endemic countries, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

How do cVDPV outbreaks happen? And why has the number of cVDPV cases in Africa increased more rapidly in the past couple years while wild cases have not?

cVDPVs can occur if not enough children receive the polio vaccine. In under-immunized populations, the live weakened virus in the oral polio vaccine (OPV) can pass between individuals and, over time, change to a form that can cause paralysis—resulting in cVDPV cases. This means that the cVDPV outbreaks we’re seeing today are revealing pockets across the continent where immunization rates are too low.