GENEVA, 26 April 2022

Today, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) announced that it is seeking new commitments to fund its 2022-2026 Strategy at a virtual event to launch its investment case. The strategy, if fully funded, will see the vaccination of 370 million children annually for the next five years and the continuation of global surveillance activities for polio and other diseases in 50 countries.

During the virtual launch, the Government of Germany, which holds the G7 presidency in 2022, announced that the country will co-host the pledging moment for the GPEI Strategy during the 2022 World Health Summit in October.

“A strong and fully funded polio programme will benefit health systems around the world. That is why it is so crucial that all stakeholders now commit to ensuring that the new eradication strategy can be implemented in full,” said Niels Annen, Parliamentary State Secretary to the Federal Minister for Economic Cooperation and Development, Germany. “The polio pledging moment at the World Health Summit this October is a critical opportunity for donors and partners to reiterate their support for a polio-free world. We can only succeed if we make polio eradication our shared priority.”

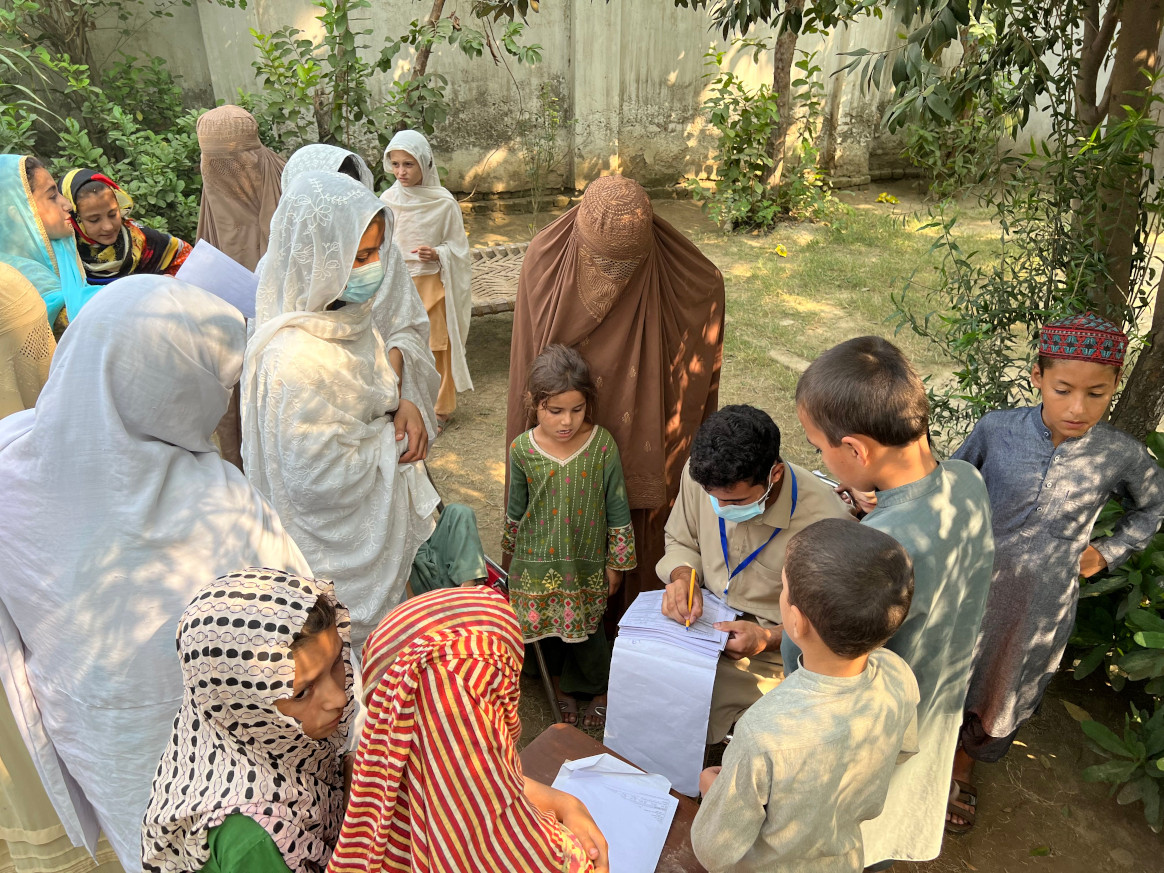

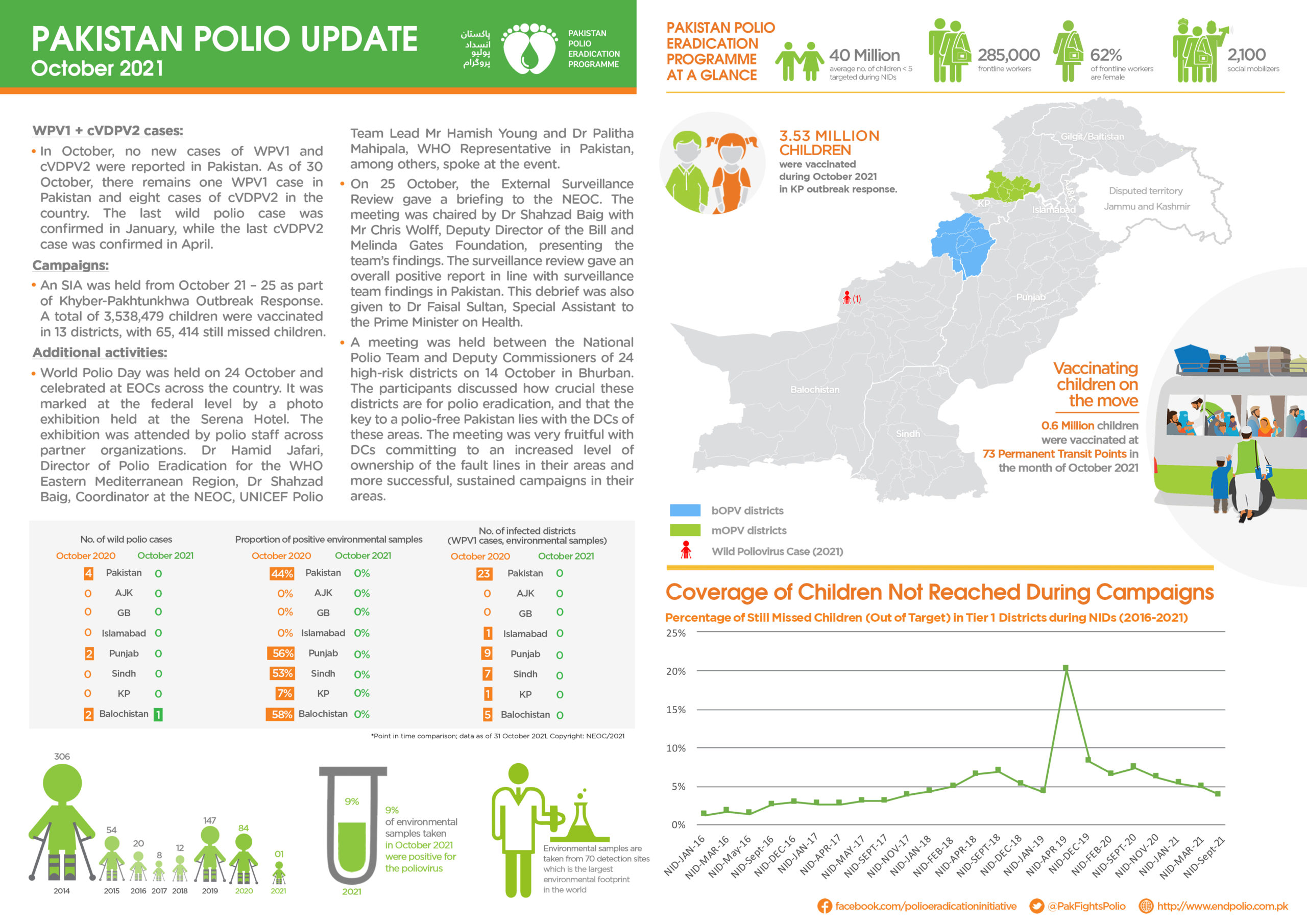

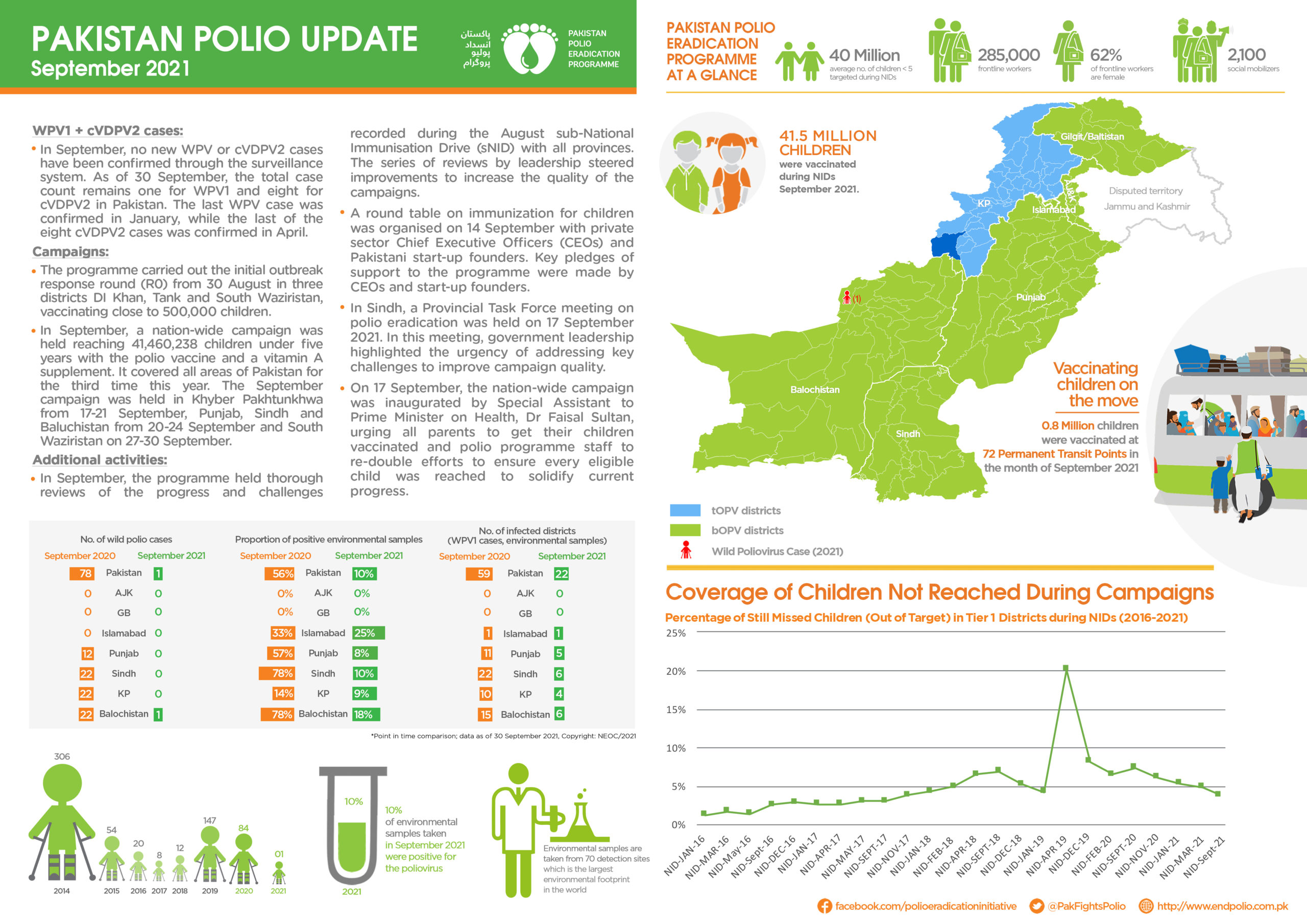

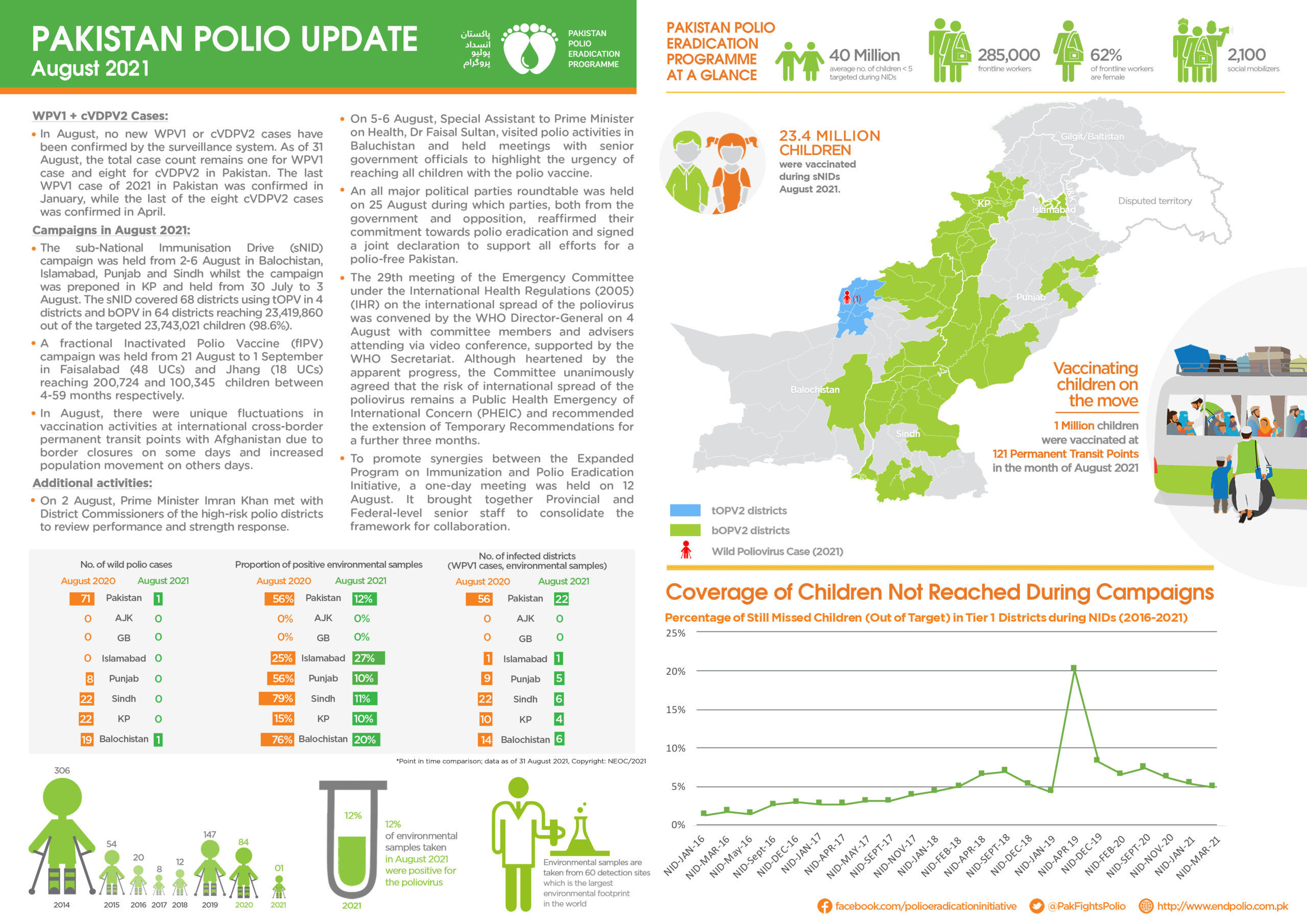

Wild poliovirus cases are at a historic low and the disease is endemic in just Pakistan and Afghanistan, presenting a unique opportunity to interrupt transmission. However, recent developments, due in part to impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, underscore the fragility of this progress. In February 2022, Malawi confirmed its first case of wild polio in three decades and the first on the African continent since 2016, linked to virus originating in Pakistan, and in April 2022 Pakistan recorded its first wild polio case since January 2021. Meanwhile, outbreaks of cVDPV, variants of the poliovirus that can emerge in under-immunized communities, were recently detected in Israel and Ukraine and circulate in several countries in Africa and Asia.

The investment case outlines new modelling that shows achieving eradication could save an estimated US $33.1 billion this century, compared to the price of controlling polio outbreaks. At the launch event, GPEI leaders and polio-affected countries urged renewed political and financial support to end polio and protect children and future generations from the paralysis it causes.

“Despite enormous progress, polio still paralyses far too many children around the world – and even one child is too many,” said UNICEF Executive Director Catherine Russell. “We simply cannot allow another child to suffer from this devastating disease – not when we know how to prevent it. Not when we are so close. We must do whatever it takes to finish the fight – and achieve a polio-free world for every child.”

“The re-emergence of polio in Malawi after three decades was a tragic reminder that until polio is wiped off the face of the earth, it can spread globally and harm children anywhere. I urge all countries to unite behind the Global Polio Eradication Initiative and ensure it has the support and resources it needs to end polio for everyone everywhere,” said Hon. Khumbize Kandodo Chiponda MP, Minister of Health, Malawi.

The new eradication strategy centres on integrating polio activities with other essential health programs in affected countries, better reaching children in the highest risk communities who have never been vaccinated, andstrengthening engagement with local leaders and influencers to build trust and vaccine acceptance.

“The children of Pakistan and Afghanistan deserve to live a life free of an incurable, paralyzing disease. With continued global support, we can make polio a disease of the past,” said Dr Shahzad Baig, National Coordinator, Pakistan Polio Eradication Programme. “The polio programme is also working to increase overall health equity in the highest-risk communities by addressing area needs holistically, including by strengthening routine immunization, improving health facilities, and organizing health camps.”

The investment case outlines how support for eradication efforts will enable essential health services in under-served communities and strengthen the world’s defences against future health threats.

Since 2020, GPEI infrastructure and staff have provided critical support to governments as they respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, including by promoting COVID-safe practices, leveraging polio surveillance and lab networks to detect the virus, and assisting COVID-19 vaccination efforts through health worker trainings, community mobilization, data management and other activities.

“The global effort to consign polio to the history books will not only help to spare future generations from this devastating disease, but serve to strengthen health systems and health security,” said Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General.

Additional quotes from the GPEI Investment Case:

“We have the knowledge and tools to wipe polio off the face of the earth. GPEI needs the resources to take us the last mile to eradicating this awful disease. Investing in GPEI will also help us detect and respond to other health emergencies. We can’t waver now. Let’s all take this opportunity to fully support GPEI, and create a world in which no child is paralyzed by polio ever again,” said Bill Gates, Co-chair, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

“An investment in polio eradication goes further than fighting one disease. It is the ultimate investment in both equity and sustainability – it is for everyone and forever. An important component of GPEI’s Strategy focuses on integrating the planning and coordination of polio activities and essential health services to reach zero-dose children who have never been immunized with routine vaccines, therefore contributing to the goals of the Immunization Agenda 2030.” said Seth Berkley, Chief Executive Officer, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

“Twenty million people are walking today because of polio vaccination, and we have learned, improved and innovated along the way. We are stronger and more resilient as we enter the last lap of this marathon to protect all future generations of the world’s children from polio. Please join us; with our will and our collective resources, we can seize the unprecedented opportunity to cross the finish line that lies before us,” said Mike McGovern, Chair, International PolioPlus Committee, Rotary International.

Downloads

Media contacts:

Oliver Rosenbauer

Communications Officer, World Health Organization

Email: rosenbauero@who.int

Tel: +41 79 500 6536

Ben Winkel

Communications Director, Global Health Strategies

Email: bwinkel@globalhealthstrategies.com

Tel: +1 323 382 2290

Sabrina Sidhu

UNICEF New York

Email: ssidhu@unicef.org

Tel: +19174761537