In March, the Afghanistan polio eradication initiative conducted its first nation-wide immunization campaign for polio eradication in 2018. In just under a week, around 70 000 workers knocked on doors and stopped families in health centres, city streets and at border crossings to vaccinate almost ten million children. What an incredible achievement.

But what does a huge campaign like this take?

We had a look behind the scenes and followed the week in Herat, western Afghanistan. See what the campaign looked like from beginning to end through this photo essay.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

First there are the vaccines. Throughout the year, millions of doses of vaccines are stored in cold rooms across the country, ready to be used in immunization campaigns. Here, cold chain manager Ghulim Said shows oral polio vaccine vials − the primary vaccine used for polio eradication − which are stored in the Herat regional EPI vaccine storage facility.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

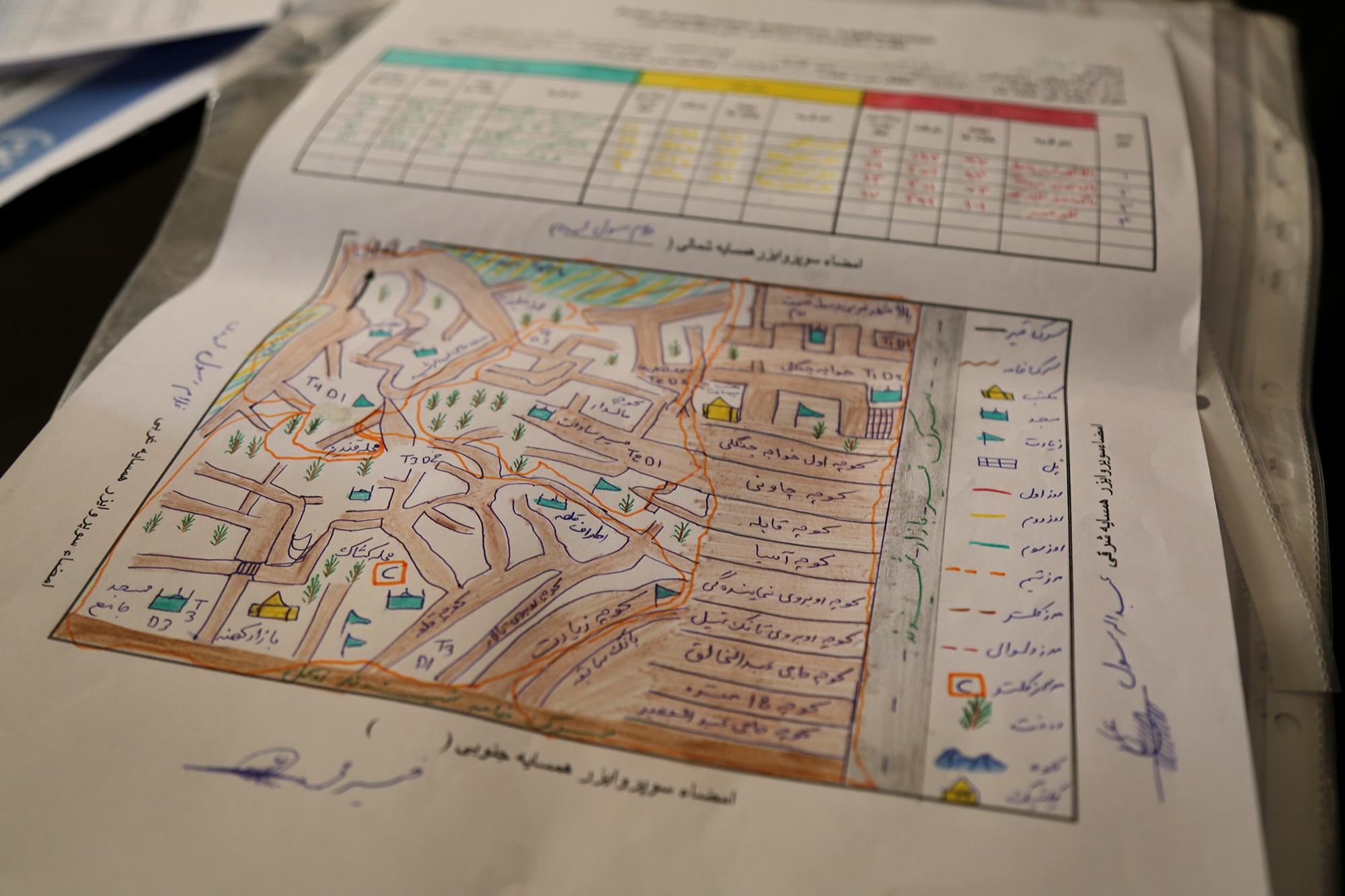

Before each vaccination campaign, the polio programme draws detailed maps of where each team will head. These maps are called “microplans” and they show streets, landmarks and each house that vaccinators must visit during the campaign days.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

A week before vaccination begins, polio workers start preparing. For this campaign, more than 70 000 volunteer vaccinators and other polio workers were selected and trained in vaccination, finger marking and campaign monitoring. In Herat, students Jami Mansoora (left) and Asma Hakimi (right) were trained as campaign monitors.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

One day before the campaign, vaccines and other supplies were picked up from storages to be taken to the teams. These vaccines were taken from Herat regional hospital to a nearby district. They were kept in cold boxes to maintain vaccine quality.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

To mark the start of the week-long effort, inauguration ceremonies were held across the country. Herat provincial governor Asef Rahimi vaccinated local children during one such ceremony.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

On the first day of the campaign, banners were hung on roadsides, mosques, and health centres all over the country announcing the campaign and encouraging parents to vaccinate their children. This banner was hung on the side of a busy street in Herat city.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

In the morning, the blue boxes used to keep vaccine vials cold were packed and picked up by the vaccination teams. Shireen Gul Azizi packed her bags before leaving for the day’s work. She works as a supervisor and manages three vaccination teams.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

With the teams on their way, vaccination began. They walked from door to door, knocked and gave two drops of polio vaccine to every child they could find.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

Ali Yaser, age 4, was vaccinated on the first day of the campaign in Herat city. All vaccinated children were also given drops of vitamin A to boost their immunity.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

The children had their fingers marked with blue pen after being vaccinated. Four-year-old Mahsa smiled as she received her finger mark.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

In addition to the house-to-house teams, mobile and transit teams worked across the country to reach any children on the move. At the border crossings, travellers were stopped and their children vaccinated. At these points, all children under ten years old are vaccinated. Mohammed Hussain Farhang, age 6, was returning from a holiday in Iran with his family. At Islam Qala border crossing vaccinator Bashir Ahmad gave him two drops of polio vaccine. He found finger-marking funny and couldn’t stop giggling.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

During the campaign week, mobile teams also vaccinated children on the streets and outdoor markets. Farzad, age 16, was working by himself in the centre of Herat. In a single day, he vaccinated tens of children.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

Every evening after the rounds, the vaccinators and cluster supervisors got together for a meeting to discuss any problems that might have been encountered during the day’s work.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

On Thursday, three days into the campaign, the vaccinators took a break and collected numbers on how many children had not been home or had missed vaccinations for other reasons. Detailed plans were drawn and maps created showing each team which houses still needed to be revisited on the last day.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

In some places, more vaccines were needed. Rickshaw driver Khalil Ahmad played his part in ensuring that every team had enough vaccines, driving more supplies to a neighboring district for the final revisit day.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

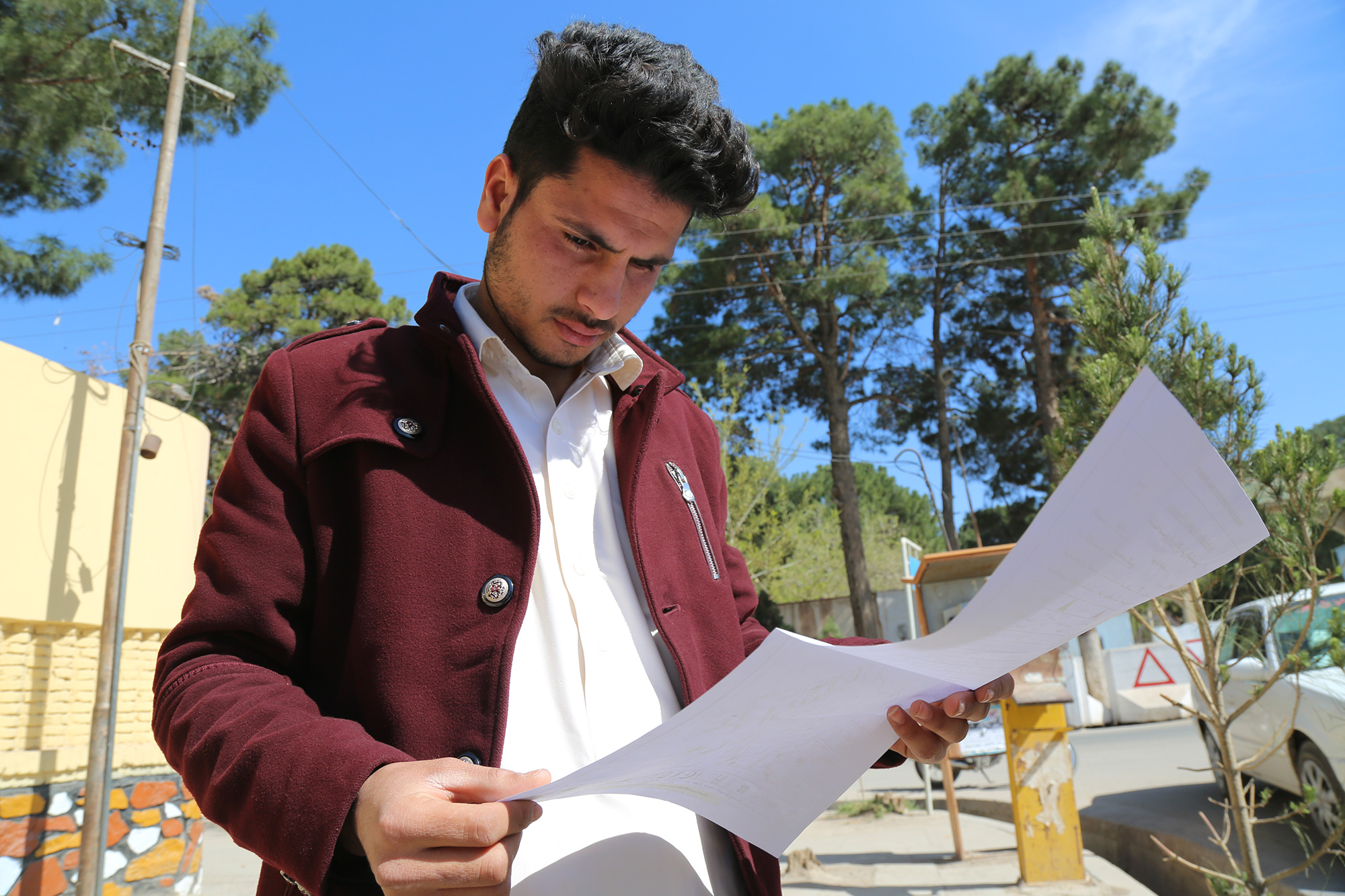

On the morning of the last campaign day, cluster supervisor Ahmad Rashid examined his map to see where the five vaccinator teams he managed would be heading. He knew the revisit day was important during every campaign: this was the chance to reach every last child in his area.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

One of Ahmad Rashid’s teams, vaccinators Sumaya Hakimi (left) and Sohaila Hamidi (right), started working at eight in the morning. From their maps they could see that they had missed 36 children during the week. By 11 a.m., they had already found 30 of the children at home and had vaccinated them.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

Success! Moheburrahman, age 3, was not vaccinated earlier in the week when the team visited, as his mother was worried about the vaccine’s safety. The team talked with the family again, carefully explaining why the polio vaccine is so important, and taking time to discuss their concerns. Reassured that the vaccine is safe, little Moheburrahman’s mother allowed the vaccination to go ahead.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

One last child protected against paralysis. Little one-day-old Fatima received her first ever vaccination on the last day. She could not be vaccinated earlier, as she had not been born yet.

© WHO Afghanistan / Tuuli Hongisto

After the campaign, more than 1 800 independent monitors were deployed to find any missed children and record the reason they were missed. This information will help preparations for the next campaign.

In a local health centre in Herat, Najibullah Mohammadi conducted a finger-marking survey to check if every child had a little blue pen mark on their fingers. On little babies the mark was drawn on the ear – an easy way to show they have been vaccinated whilst keeping them wrapped up warm. 45-day-old Rokshana was found to be vaccinated.

Rokshana and every child deserves a healthy, polio-free life. Thanks to the work of the thousands of volunteers and polio workers, Afghanistan is one step closer to eradicating the disease.