As the world edges closer to becoming polio-free, keeping up the guard in countries at high risk of polio importation is more of a priority than ever. With polio continuing to circulate in the three remaining polio-endemic countries – Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria ‒ any country is at risk of the virus returning.

Vulnerable to the Virus

Among the most vulnerable of at-risk countries is Somalia. A poor country plagued by decades of civil strife, Somalia is home to 1.1 million internally displaced persons. Shortages of resources and constant insecurity hamper the ability of the country’s health system to provide essential and equitable health services, including routine immunization, to its population.

In Somalia, community members in inaccessible areas are leading the way, playing a crucial role in the polio surveillance system to make sure that insecurity and inaccessibility do not give the poliovirus a free pass to return.

The prospect of polio returning to Somalia is not an idle threat. Three years ago, after six years polio-free, Somalia was rocked by an explosive polio outbreak that paralysed close to 200 children in the Horn of Africa neighbourhood. As the epicentre for the outbreak, Somalia accounted for more than 90% of cases, with Kenya and Ethiopia also affected. Following a swift multi-country immunization response led by national governments and partners of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, polio transmission was stopped and the outbreak was declared closed after 18 months. The affected countries and their neighbours have since been working hard to keep polio at bay. For Somalia, this has called for new and innovative tactics.

Searching for polio in inaccessible areas

“In some areas of the country controlled by non-state armed groups, access to communities for health teams is heavily restricted or completely barred,” said Dr Eltayeb Elfakki, who is responsible for managing polio eradication efforts for WHO Somalia. “Inaccessibility not only makes it difficult for us to ensure that every single child under five years of age in those communities is vaccinated against polio multiple times, but it also compromises time sensitive surveillance which enables us to quickly pick up traces of the poliovirus, should it resurface,” he said.

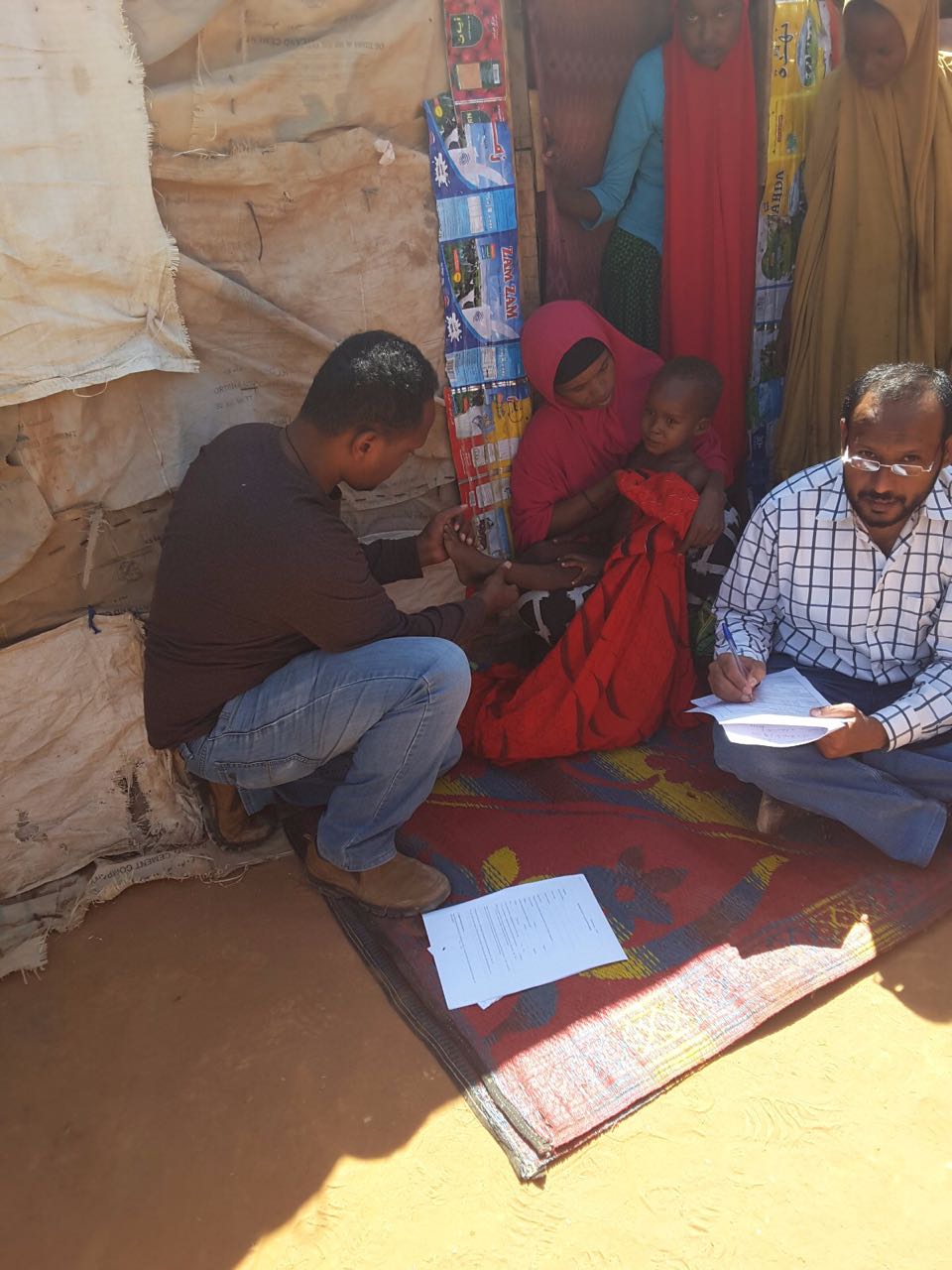

In ‘no-go zones’, WHO and partners rely heavily on the support of community members to actively seek out and report cases of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) – a major indicator for polio characterized by ‘floppiness’ in limbs. This network of local village polio volunteers (VPVs) – students, mothers, fathers, and community leaders – are trained by WHO to recognize symptoms of AFP and on reporting protocols, and travel from house-to-house in their villages or towns observing children for signs of paralysis. When AFP is detected, the case is immediately reported to a district focal point and a case investigation is mounted. Stool samples are collected from cases and transported to a reference laboratory in Nairobi, Kenya, where they are tested to confirm or rule out polio as the cause for paralysis.

“Traditionally, active searching for AFP cases is done by surveillance or medical staff from the Ministry of Health. However, in Somalia, we’ve had to think outside the box due to a shortage of health workers, and this has been extremely effective. VPVs are trusted members of their communities and have been very helpful in sensitizing their peers and neighbours on what to look out for and what to do, when it comes to AFP. They also advocate for polio vaccination and help in the dissemination of other important health messages.”

Seeing results

Currently, volunteers in Somalia account for over 60% of AFP cases reported nationwide, with each volunteer visiting on average between 40-60 households per week. The network consists of over 500 volunteers who are active in 19 regions of the country.

“We are grateful for the vital assistance these community members give us, and commend their dedication to the goal of protecting Somalia from future [polio] outbreaks,” said Dr Elfakki. “It goes to show that success in polio eradication depends on the close and strong collaboration between all partners including national and local governments, public and private health providers, civil society, religious institutions, and most importantly community members themselves,” he said.