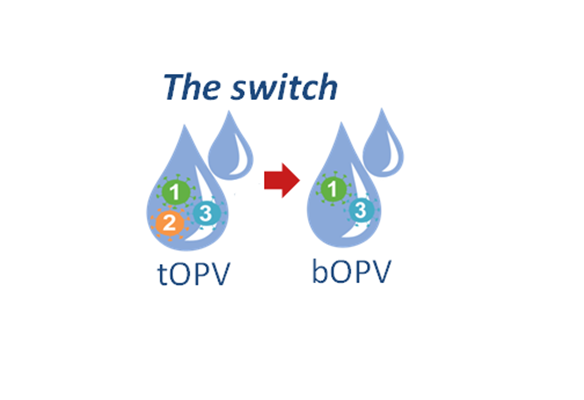

Convening in Geneva, Switzerland, on 20 October 2015, the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on immunization (SAGE) confirmed that the globally coordinated withdrawal of the type 2 component in the oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) should occur in April 2016, specifically in a window from 17 April to 1 May 2016. Countries should soon begin to intensify their preparatory efforts to switch from trivalent oral polio vaccine (tOPV) to bivalent OPV (bOPV) to meet this timeline.

SAGE’s landmark decision follows the endorsement by the World Health Assembly (WHA) in May 2015, when Ministers of Health from 194 member states adopted a resolution on the global effort to eradicate polio, paving the way for a world free of polio.

SAGE concluded that significant progress had been made since its last meeting in April 2015, with no cases in Africa since August and over a year having passed since the last case in the Middle East was seen, strengthened surveillance and more children being reached with vaccines in key areas of Pakistan and Afghanistan. As a result of these steps, all countries and the partners of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) should plan for April 2016 as the definitive date for the global withdrawal of OPV type 2 (OPV2).

Withdrawing OPV type 2 is a crucial part of the polio endgame strategy, in order to eliminate the very rare cases of vaccine associated paralytic polio (VAPP) or circulating vaccine derived polioviruses (cVDPVs). The type 2 component of OPV accounts for 40% of VAPP cases, and upwards of 90% of cVDPV cases. By contrast, wild poliovirus type 2 has not been detected anywhere since 1999 and the Global Commission for the Certification of Poliomyelitis Eradication (GCC) declared this strain globally eradicated at its meeting in September 2015.

SAGE cautioned, however, that more work needs to be implemented ahead of the April 2016 switch date. It is critical that countries meet established deadlines to protect populations by moving the world towards destruction of wild poliovirus type 2 stocks or their appropriate containment in designated ‘poliovirus essential’ facilities. Ongoing cVDPV2 outbreaks in Guinea and South Sudan needed to be fully stopped. And a global supply constraint of inactivated polio vaccine needed to be carefully managed in the lead-up to the switch. The level of commitment from countries to meet the deadline to introduce IPV ahead of the switch has been exceptional, however due to technical challenges in scaling up manufacturing, short term supply constraints mean that some countries that are at low risk of cVDPV2 emergence and circulation are expected to experience slight delays in deliveries. The available supply must be prioritized to highest risk areas and stocks set aside for use as part of a response to detection of a type 2 poliovirus after OPV2 withdrawal.

The withdrawal of type 2 OPV will ultimately eliminate the risk of emergence of new cVDPV2s in the future, and will also prevent upwards of 200 cases of VAPP that currently occur each year as a result of the type 2 component in trivalent OPV. This globally synchronised switch will therefore be of great significance for the polio eradication programme with tremendous public health benefits.

Conclusions and recommendations as published 11 Dec 2015 in Weekly Epidemiological Records no. 50