When the search for wild poliovirus is literally a drop in the bucket

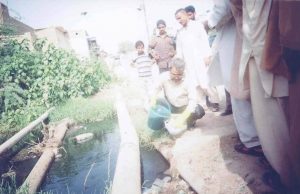

02 April 2012 – Once a week, in the most crowded quarters of Quetta, Pakistan and Mumbai, India, teams of people wearing aprons and gloves stand together on bridges, carefully lowering buckets into the running streams of open sewage. Similar scenes, with variations, can be witnessed in many countries, including Nigeria, Egypt, Senegal , Indonesia, Finland and Israel.

Passers-by are forgiven for shaking their heads: it looks like they’re fishing in sewage, and in fact, they are. They’re fishing for wild poliovirus.

‘Environmental sampling’ has become a key strategy in the hunt for the final reservoirs of polio globally. Just one in 1,000 children infected by type 3 polio becomes paralyzed by the virus, meaning 999 out of 1,000 children carry the virus silently, infecting entire communities. Similarly, only one in 200 children infected with type 1 polio become paralyzed. Sewage sampling allows the polio eradication initiative to clearly determine whether the virus is circulating in what otherwise appears to be a healthy town or village.

Samples, once collected, are quickly placed in cool boxes and transported to one of the Global Polio Laboratory Network’s 145 laboratories for testing. Positive samples indicate that the virus is circulating in the area, even if no one has been paralysed by polio. This tells us that acute flaccid paralysis may be insufficient, and triggers supplementary immunization activities to boost immunity in the vicinity of the positive sample.

Samples, once collected, are quickly placed in cool boxes and transported to one of the Global Polio Laboratory Network’s 145 laboratories for testing. Positive samples indicate that the virus is circulating in the area, even if no one has been paralysed by polio. This tells us that acute flaccid paralysis may be insufficient, and triggers supplementary immunization activities to boost immunity in the vicinity of the positive sample.

A former coordinator of the laboratory network, Dr Esther de Gourville, described wild poliovirus infection as an iceberg, with the paralyzed cases being the tip of the iceberg. Environmental sampling is a way of being able to see what is hiding beneath the surface.