Monday 6 June

Arrive Kabul at 9.30am, my first visit in two years and the city has lost none of its bustle.

A review team last visited here in 2016 but access was limited. Much has changed – both within Afghanistan and for polio – since then. The programme now has access across the country and the epidemiological picture has changed dramatically. In 2020, 56 children were paralysed by the virus. So far this year only one child has been paralysed giving Afghanistan its strongest chance yet of interrupting polio transmission.

Surveillance underpins the eradication of any virus. For polio, it consists of monitoring for signs of Acute Flaccid Paralysis or AFP in children under 15 years, and collecting samples of sewage, what we call environmental surveillance, to check for the presence of the virus in the community.

We’re here to apply a magnifying glass to Afghanistan’s surveillance system, to see if there’s anywhere the virus might still be hiding and recommend adjustments to make sure the system is capable of catching it.

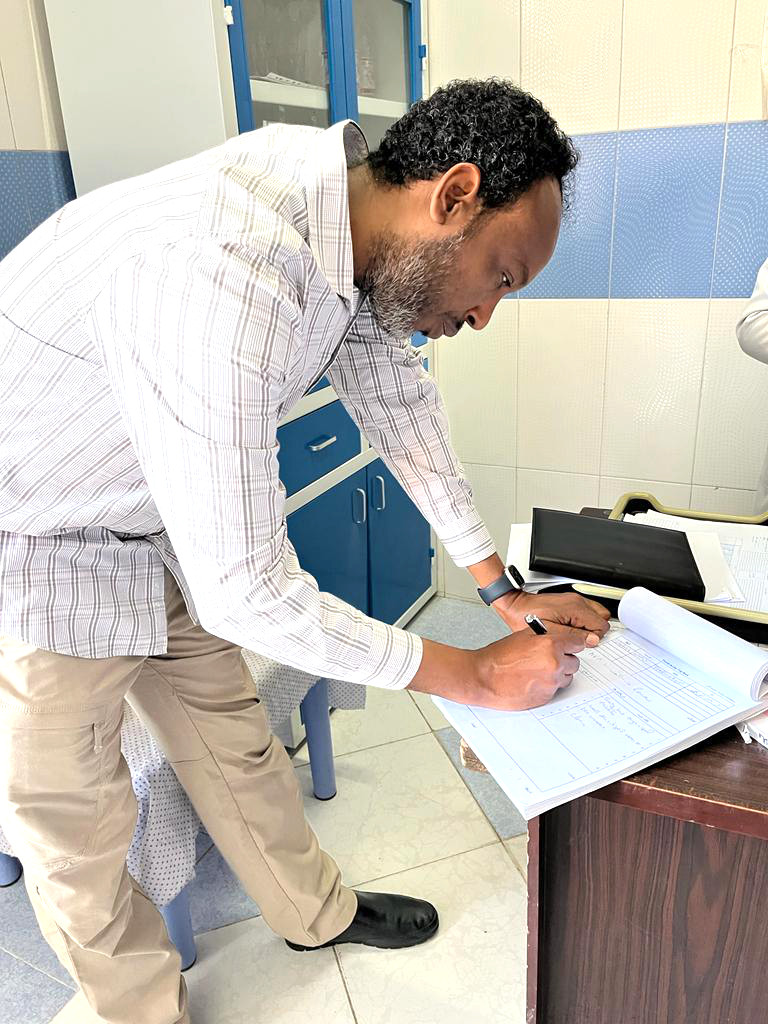

If polio surveillance is about gathering data and documenting it meticulously, it’s even more so for a surveillance review. Our job includes checking documents and records, interviewing health workers and families of children with AFP, reviewing guidelines and standard operating procedures – checking and rechecking data.

Wednesday 8 June

After meetings yesterday, including briefing the National Emergency Operation Center (EOC), the operational heart of the polio programme here, I head to Herat in the country’s west where my first stop is the WHO office. I meet the polio team before moving on to the Regional EOC where we discuss the objectives of my mission. I review records before checking the cold room where vaccines are kept. There’s a corner for stool specimens that come in from the western region. Part of the process of checking children with signs of AFP is collecting stool samples that are then sent to the regional laboratory in Pakistan for testing. Reviewing the collection, storage and shipping of these samples is part of my remit as a reviewer.

Thursday 9 June

At a hospital in Herat city, I meet with the AFP focal point – a pediatrician. All major health facilities have an AFP focal point who acts as the link between the facility and the broader surveillance system. I ask him about his background, the facility’s stool handling, preparation and shipment, and the work of the hospital.

In the afternoon, I examine two children affected by AFP earlier in the year. I talk to their parents and ask them the same questions they were asked by the initial investigating surveillance officer. I do this to check the accuracy of the information collected during the original case investigation and to see if there are any discrepancies.

Friday 10 June

Friday – the only holiday of the week. I spend it at the WHO office going through documents including AFP case files and data. It’s also a good opportunity to enter all the information I collected over the previous two days into the online tool developed specifically for this review.

Saturday 11 June

We set out early to a district near the border with Iran, two hours’ drive away. First stop is a very busy Comprehensive Health Center (CHC). It’s reported six out of the eight AFP cases from this district this year. I meet with the director, doctors, nurses, and other staff. Beneath their facemasks, their smiles are beaming. They speak with pride of their clinic and, like all the health facilities I visit, it’s spotlessly clean.

In the afternoon, I meet with the community health supervisor who oversees 16 community health workers (CHWs) working in village health posts nearby. Village health posts play an important role in community-based polio surveillance. I review the curriculum and training agenda to check what information is captured.

Sunday 12 June

I spend the day in the districts surrounding Herat city. My meetings include a visit to a traditional healer who fixes broken bones among other ailments, and a CHW who is an imam at a local mosque. Both are reporting volunteers in the 46,000-strong community-based surveillance network that keeps an eye out for polio among their communities.

Monday 13 June

I visit an environmental surveillance site in Herat city. Samples are taken from sewage on a regular basis and shipped to the lab in Pakistan to determine the presence of poliovirus. I assess the site to see if it meets quality standards, check its location to make sure it’s in the right place to catch a good enough sample, the flow of the water and its appearance. I watch as trained staff from the local municipality collect a sample to determine whether the SOPs are adhered to.

Tuesday 14 June

To neighbouring Farah province, a round trip of about eight hours. At a CHC, a boy is brought in who was referred by a local faith healer. I observe the staff examine the child, and then visit the faith healer who tells me he inherited the knowledge of healing from his father and has been doing it now for over 20 years. It was heartening to hear him talk of his collaboration with the polio team for both AFP surveillance and immunization campaigns.

Wednesday 15 June

Last day in Herat city and I debrief the team in the REOC. Our flight back to Kabul departs late and we stop in Bamyan in the central highlands to collect two other passengers, including my fellow reviewer assigned to the Central Region.

The rest of the review team makes its way back to Kabul in the remaining days. We’ve all been doing the same thing – verifying, checking, interviewing, collating data. Our next task is to compile our report and provide any recommendations to the programme to make sure Afghanistan’s polio surveillance system catches every last virus, no matter where it may be hiding.