For the last two decades, the prospect of sending 16 visiting polio experts out across the provinces of Afghanistan would have been impossible but from 6 to 19 June 2022, WHO Afghanistan’s polio eradication programme did just that. Their mission? To review the country’s polio surveillance system, assess its functionality at all levels and make specific recommendations for maintaining and improving surveillance quality.

“It was an extraordinary achievement by WHO Afghanistan’s polio team. The logistic and administrative challenges alone were enormous,” said Dr Luo Dapeng, WHO Representative in Afghanistan. “Afghanistan is one of the last countries where polio is endemic and we must do all we can to stop this virus from infecting any more children.”

The review was necessary for several reasons one of which was to ascertain whether the sharp decline in the number of children paralysed by wild poliovirus in Afghanistan in the last eighteen months was an accurate reflection of the reality on the ground. From 56 cases in 2020, the number dropped to four in 2021. So far this year, two children have been paralysed by the virus.

“It’s important to show that the surveillance system has the strength and the ability to detect any poliovirus circulation that may be happening,” said Dr Irfan Elahi Akbar, Polio Team Leader at WHO Afghanistan. “Because if we don’t detect and investigate cases quickly and respond, more and more children will be paralysed.’

The last international surveillance review team visited in 2016, meaning a review was also overdue. Insecurity and the polio programme’s lack of access to much of the country meant the small team could visit just a handful of locations including the cities of Kabul, Herat, Kandahar, Jalalabad, Mazar-e-sharif and Kunduz.

This time round, the reviewers visited 76 districts in 25 of the country’s 34 provinces, interviewing 899 people, among them volunteers who form part of the community surveillance network made up of more than 46,000 people including pharmacists, community health workers, faith healers, nurses, imams, and bone fixers.

Following a desk review of the system late last year in which the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) partners Hub in Amman analysed the existing country data, a physical visit was necessary in order to verify the findings and get as accurate a picture as possible of the surveillance system.

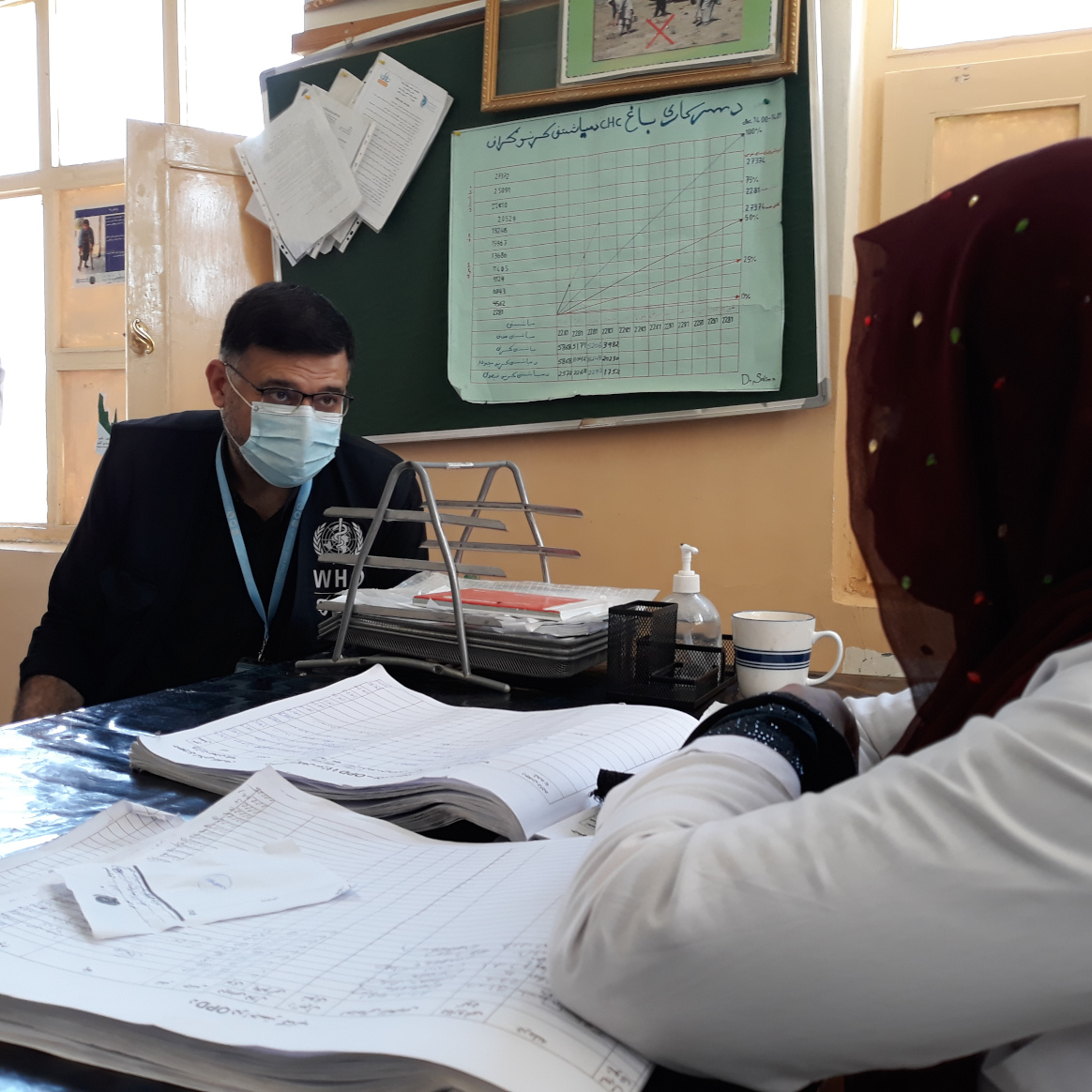

“A surveillance review is a very rigorous process that involves examining records and documents of cases of acute flaccid paralysis [AFP, a sign that polio may be present] in children, talking to patients and their families, assessing the knowledge of the many people involved in the surveillance network, scanning hospital records, checking, and rechecking data,” said Dr Khushhal Khan Zaman, who oversees polio surveillance for WHO Afghanistan.

The ultimate goal of Afghanistan’s polio eradication programme is for the country to be certified polio free, a long and meticulous process that relies on documentary evidence to show there has been no wild poliovirus transmission for a period of at least three years since the last reported case.

The reviewers’ remit also included monitoring the collection and shipment of stool samples to the Regional Reference Laboratory in neighbouring Pakistan as well as ensuring the protocols for environmental surveillance, involving the collection of sewage samples, are adhered to. Sixteen of Afghanistan’s 29 environmental surveillance sites were visited by the review team including four in Kandahar city. The review team also met with the country’s AFP Expert Review Committee to further understand Afghanistan’s review process.

The review took place in June during a window that opened between a series of nationwide polio vaccination campaigns. Each campaign takes roughly 21 days to get off the ground. With access to all parts of the country, in the first six months of 2022, the Afghanistan programme implemented five of the six campaigns planned for the year. Additional campaigns are planned for the remainder of 2022.

The logistics of getting the reviewers into Afghanistan and out to the provinces proved the greatest challenge, something akin to a game of snakes and ladders involving UN guesthouses, armoured vehicles, and the availability of security escorts. The surge of UN personnel in Afghanistan following the August 2021 transition has led to increased demand for all three. Each time one part of the puzzle became unavailable, the organizing team comprised of logistics, administration, security and travel staff scrapped their carefully constructed colour-coded spreadsheet and started again. Fortunately, the review’s logistics were very much a ‘One UN’ effort with sister agencies stepping in to fill gaps in accommodation and transport wherever possible.

Perhaps the most important support came from polio staff in the provinces who set up visits to 152 health facilities as well as interviews with hundreds of health workers, volunteers, patients and families.

The review determined that Afghanistan’s surveillance system is achieving all sensitivity targets and the likelihood of undetected poliovirus transmission is low. Recommendations, including upscaling surveillance in the country’s south and south east, are currently being implemented.

“After many visits to Afghanistan, this was the first time we were able to visit every place we needed to review,” said Dr Jean-Marc Olive, Surveillance Review Team Leader. “This gave me great confidence that this extensive effort was a thorough country review which clearly identified both the achievements and the remaining challenges to ensure that no WPV will be missed.”