2022 may well go down in history as the year of contrasts in the global effort to eradicate polio. At first glance, with polio detections in places such as New York and London and an increase in cases in Pakistan, it may seem that the effort is backsliding. And while any detection of any poliovirus is a setback—particularly in areas where the disease had been long gone, like southeast Africa—a deeper analysis reveals a more encouraging story: 2022 saw perhaps some of the most significant progress in the programme’s history, and has set up the global polio effort for a unique opportunity to achieve success in 2023.

Endemic wild poliovirus transmission in both Pakistan and Afghanistan is becoming increasingly geographically restricted, with fewer virus lineages remaining active. The bulk of variant type 2 polio (cVDPV2) cases are also becoming more restricted, with 90% of all global cases restricted to three ‘consequential geographies’ (eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, northern Yemen and northern Nigeria). And emergency outbreak response efforts to wild poliovirus type 1 in southeast Africa continue to gain momentum.

To evaluate this progress as 2022 draws to a close, independent technical expert and advisory groups are taking an in-depth look at the prevailing epidemiology, assessing impact of eradication efforts and putting forth key strategic approaches to enable an all-out effort against the virus in the first half of 2023.

The first of these groups met in early October, when the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) for Pakistan reviewed vaccination coverage and disease surveillance across the country. Despite the increase in new cases, the TAG found the outbreak to be extremely geographically confined, thanks to concerted emergency efforts led by the government and supported by partners. Today, polio transmission is restricted to the six districts of southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province—a fraction of the country’s 180 districts. Encouragingly, the virus has not re-established a foothold outside the core outbreak zone, meaning the traditional reservoirs of Karachi, Peshawar and Quetta are no longer endemic to the virus, a historical first.

More good news came out of the TAG’s analysis of the genetic biodiversity of virus transmission. In 2020, Pakistan had 11 separate chains of virus transmission. This was reduced to four in 2021, and today, just one family of the virus remains in the country. The approaches being implemented in Pakistan are working—despite some serious challenges.

In September, Pakistan experienced catastrophic flooding that impacted more than 33 million people and submerged one third of the country under water. In the face of this tragedy, and despite being affected themselves, polio staff supported the broader relief efforts while adapting polio operations to ensure that the eradication effort could continue unabated. Long-time polio eradicator and Director for Polio Eradication in WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean Region, Dr Hamid Jafari, said: “Rarely have I seen such commitment and dedication than I have seen in Pakistan – from national leaders, to health workers, right to the mother and father on the ground.

They are making a huge difference to people’s lives, which goes far beyond the effort to eradicate polio.”

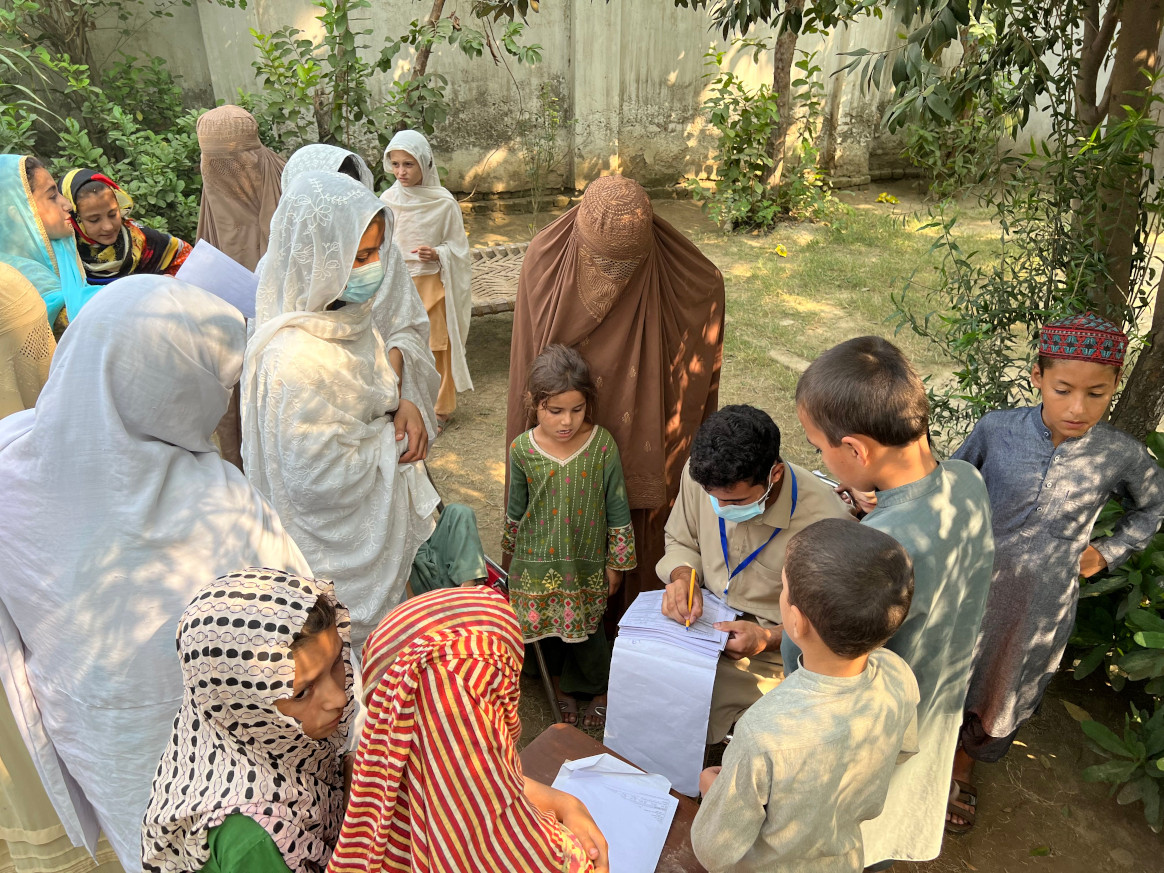

In December, a high-level delegation led by GPEI Polio Oversight Board (POB) Chair Dr Chris Elias, WHO Regional Director Dr Ahmed Al-Mandhari and UNICEF Regional Director George Laryea-Adjei visited Pakistan during a nationwide vaccination campaign. After meeting with women health workers, provincial and national polio coordinators and even the Prime Minister, the group concluded that there is unprecedented support and commitment to ending polio in the country in 2023.

In Afghanistan too, an epidemiological deep dive reveals a promising picture: just over twelve months on from the political developments in the country in 2021, access to all children in the country continues to improve, albeit against a tragic backdrop of a severe and acute humanitarian crisis. More than 3.5 million children in Afghanistan who had been out-of-reach for almost five years can now be reached with polio vaccines, and thanks to strong vaccination and disease surveillance efforts, polio transmission has been restricted to just two chains in two provinces. And following the country’s devastating earthquake in June, polio teams sprang into immediate action to both support the broader emergency relief effort and adapt polio operations.

This progress in Pakistan and Afghanistan is identical to what epidemiologists observed during the ‘end game’ efforts in global polio reservoirs in the past, notably Nigeria, India and Egypt, giving rise to optimism that these remaining two endemic countries are on the right track.

Expert groups focus on outbreaks…

2022 saw a number of high-profile polio events, like the detections in New York City and London, but it is important to recognize the distinction between these and the outbreaks that have the capacity to endanger, or at least significantly delay, the global eradication goal.

Aidan O’Leary, Director of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) at the World Health Organization (WHO), contextualized the situation: “90 percent of global media attention has been on the polio emergence in New York, London and Israel. However, 90 percent of actual cases are in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, northern Yemen and northern Nigeria.” It is in those areas, commonly referred to as consequential geographies, that programmatic efforts must maintain their focus. Notably, these areas also overlap with some of the highest proportions of ‘zero-dose’ children—those who are either un- or under-vaccinated.

While the outbreaks in northern Yemen and eastern DR Congo continue to expand at an alarming rate in 2022, the situation in northern Nigeria is far more encouraging. Nigeria accounted for two-thirds of all global cases in 2021, seeding outbreaks in 19 countries. In the second half of 2022, however, there has been a dramatic decrease in new detections, with just nine cases reported during that time.

In November, the Nigerian Government, with GPEI partners in attendance, hosted the Global Roundtable Discussion on variant type 2 polio outbreaks, reviewing progress in outbreak response following the upsurge in cases in 2021. The Roundtable recognized efforts to reach zero-dose children in consequential geographies throughout the country, in particular with the novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2), as well as Nigeria’s focus on strengthening routine immunization with bivalent OPV and inactivated polio vaccine (IPV). Whichever strategy is used, however, the group cautioned: “coverage is king!” Any vaccine is only as good as the proportion of children it reaches.

The group’s conclusions and recommendations will be further evaluated by Nigeria’s Expert Review Committee on Polio Eradication and Routine Immunization (ERC).

Meanwhile, in southeast Africa, a comprehensive Outbreak Response Assessment reviewed the regional response to wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1), linked to virus originating from Pakistan, with cases confirmed in Malawi and Mozambique. Experts noted the high-level, comprehensive support for the outbreak response across the region, and that vaccination campaigns have been consistently improving with time.

At the same time, the group concluded that the outbreaks are not over. With simultaneous outbreaks of WPV1, cVDPV1 and cVDPV2 affecting in particular Mozambique, the group put forward key recommendations and strategies, building on the momentum and knowledge gained over the past six months. These conclusions were further endorsed by the Africa Regional Certification Commission for Eradication (ARCC), which met in South Africa.

Challenges remain ahead. Zero-dose children must be reached, particularly in consequential geographies. Remaining financial resources to achieve success must be mobilized. Campaigns must be strengthened in southeast Africa. But despite initial appearances, 2022 put the world on an extremely strong footing to interrupt all remaining chains of poliovirus transmission by end 2023—the goal of the GPEI Strategy 2022-2026.

There is a clear momentum as the year draws to a close. We must carry it into 2023 for a final, concerted push. Success is in our hands.