Since 1988, the number of children affected by polio has reduced by 99 per cent. While the end of polio is within reach, immunization efforts can easily be derailed by the rapid spread of vaccine misinformation, putting vulnerable children at risk.

Take for example Pakistan, one of the two countries where polio remains endemic, where fake videos of children falling sick after receiving polio vaccination spread like wildfire on social media a few years ago. The misinformation caused mass panic and derailed long-fought efforts to immunize millions of children across the country.

While it is near impossible to eliminate misinformation after it has spread, national health systems can actively monitor for and address misinformation as it arises. This is where the Digital Community Engagement (DCE) initiative is proving effective. Based on the Vaccine Misinformation Management Guide, the DCE was launched as a first-of-its kind misinformation management model in 2021 by UNICEF and The Public Good Projects.

The DCE is made up of a central hub that tracks polio misinformation online, develops accurate messaging, and supports digital volunteers and UNICEF country offices. The hub is driven by a global team of experts spread across public health, social behaviour change, online social listening, advertising, content design and influencer marketing.

The DCE is made up of a central hub that tracks polio misinformation online, develops accurate messaging, and supports digital volunteers and UNICEF country offices. The hub is driven by a global team of experts spread across public health, social behaviour change, online social listening, advertising, content design and influencer marketing.

“In many countries, UNICEF and partners are already working to combat online misinformation in various ways. DCE’s aim is not to replace these systems but strengthen their existing efforts,” said Adnan Shahzad, the Digital Communication Manager of the UNICEF Polio Eradication Team.

The polio ‘listening post’

“Social listening is like a disease surveillance system, but instead of the virus, we track and analyze misinformation. Using cutting-edge digital media and tools we collect and analyze publicly available data on polio and vaccines across social media, digital media, broadcast news and print media platforms,” said Shahzad.

In 2022, over 5 million online social listening results were analysed from 41 countries in more than 100 languages. The most common misinformation pieces claimed that vaccines were unsafe and that they could cause other diseases. Other fear-inducing misinformation involved how vaccines are being used by rich countries or individuals to control the world and depopulate certain continents.

Misinformation pieces are analysed and categorised as low, medium or high risks based on its potential impact to vaccination efforts and how quickly it is spreading. When a high-risk misinformation is going viral (within a 24-hour period), the DCE central hub sends an urgent alert to UNICEF country and regional offices and also sends a weekly compilation of news and alerts in the form of a newsletter

Examples of high-risk misinformation alerted to country teams:

- Polio detection in U.S. sparks misinformation about polio vaccines

- Posts question why vaccines are being distributed after disasters

- Thread blames vaccines for polio outbreaks

- Rumors circulate that the polio vaccine is unsafe and causes AIDS

- Houthi leader allegedly claims vaccines are satanic and anti-Islam

Clear and accurate messages are crucial

Clear and accurate messages are crucial

“What we say must be accurate and easy to understand for everyone,” says Soterine Tsanga, Polio Outbreak Response SBC specialist with UNICEF, who is also involved in the roll out of DCE to countries. “When there’s a polio outbreak, our goal is to respond swiftly to reach children with vaccination and stop further spread of the virus. We cannot afford to have our own messaging causing confusion among mothers and fathers,” she adds.

Backed by scientific evidence and facts, messages on polio are carefully prepared at the DCE hub in English, French, Urdu and Pashto. The team organizes content into a bank for quick retrieval based on reoccurring themes, such as vaccine effectiveness, safety and side effects.

Quashing rumours

“A big part of UNICEF’s social behaviour change work for polio eradication involves engaging local community mobilisers who continuously listen to concerns about vaccines, clarify doubts and encourage parents and caregivers to vaccinate their children. DCE is the online version of this approach aimed at engaging online communities to quash false information before it becomes viral,” said Sheeba Afghani, the Chief of Social Behaviour Change with the UNICEF Polio Eradication Programme.

The DCE hub recruits digital volunteers through an interactive online platform called uInfluence to promote accurate polio and vaccine information. Digital volunteers or ‘uInfluencers’ are everyday social media users, many of them young people who are already active in online communities.

“I grew up seeing many people suffering from polio and other diseases. We struggled to find solutions for the problems in our community. I want to help by being a source of accurate information about polio,” said Liam, a 26-year-old digital volunteer.

Liam is one of 75,000 digital volunteers working with uInfluence. They repurpose content shared by uInfluence on Facebook and Instagram, dispel vaccine and polio misinformation, and increase engagement on social posts. In 2022, content posted through uInfluence channels and amplified by digital volunteers reached 74 million people.

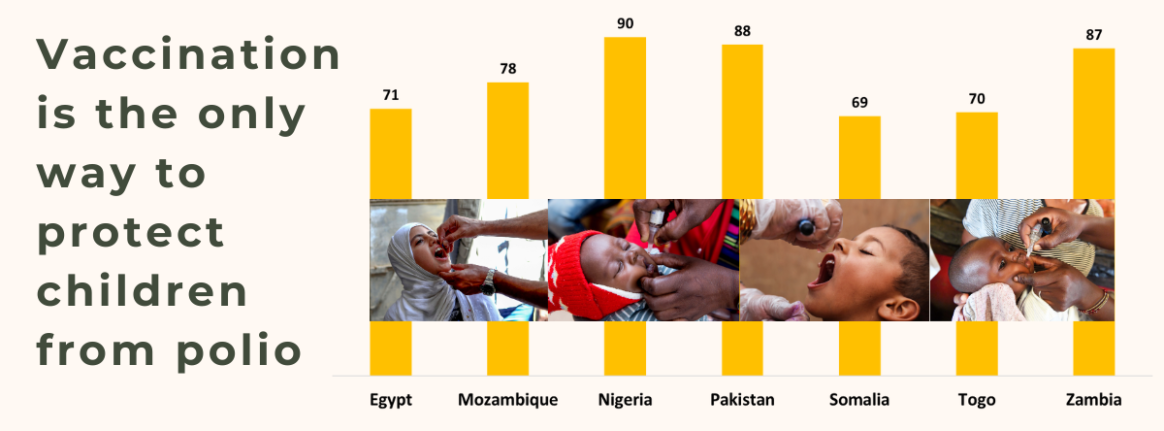

DCE’s general population advertisement (ad) campaign has also yielded positive results. An ad campaign in January 20203 on Facebook and Instagram encouraged parents and caregivers between ages 18–45 years in Egypt, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, Somalia, Togo and Zambia to visit the “Polio Facts” page on the uInfluence website. By March 2023, the campaign had reached 7.6 million parents. A post-campaign survey with the target populations helped identify knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about vaccine safety, efficacy (See Figure 1.) , and polio risk, likelihood of vaccinating children, recommending the vaccine to others, and sharing information on the vaccine.

Local outreach and digital engagement

“The concept behind establishing the DCE central hub was to offer enduring tools for country offices, enabling them to craft localized digital health communications and establish a system that mirrors the central hub,” said Andrea Valencia, the Global Program Manager at PGP.

“DCE presents a significant opportunity for countries to prioritize their communication efforts by employing best practices in messaging. This enables them to bridge the gap between their on-the-groundwork and digital communities, while fostering trust in childhood immunization,” she added.

Pakistan’s polio eradication programme has managed several misinformation crises in the past, many of them about the polio vaccine. In October 2022, a Facebook post falsely claimed that a child had died after receiving the polio vaccine in Balochistan, when in fact she had succumbed to severe pneumonia. The polio social media team responded quickly with a video message from the doctor who had examined the child, stating the real cause of death. Meta and the Pakistan Telecom Authority were alerted as it posed a high risk to the polio vaccination campaign. Meta’s independent Fact Check Team called Soch launched an independent investigation and published an articlediscrediting the misinformation.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, UNICEF is tapping into its network of young fact checkers (Veilleurs du Web) and U-Reporters to tackle misinformation online and offline using DCE tools. During a polio vaccination campaign in July 2023, U-Reporters spoke with mothers and fathers about polio vaccines in markets, churches and mosques while the fact checkers tracked and responded to fake news and rumours related to polio vaccines.

In Afghanistan, religious leaders are building trust in polio vaccines through their sermons in madrassas, or Islamic schools, and mosques. In Kandahar, an Islamic radio programme helps assuage fears and misinformation about vaccines. The national authorities have also offered their support in managing polio vaccine misinformation. Moving forward, the country is planning to establish a misinformation management taskforce at regional and national level to effectively manage polio vaccine misinformation.

In Yemen, DCE trainings helped the Ministry of Public Health, Social Services Centre, Community Radio stations and a Helpline for Internally Displaced Persons collaborate in establishing basic tools to track rumours and misinformation. They have also expanded the existing COVID-19 helpline managed by medical doctors to track misinformation, respond with accurate information on other health issues, and shar monthly reports with all health partners. Based on the DCE polio message bank model, Yemen is now developing similar resources on measles and oral cholera vaccines.

More opportunities ahead

“DCE can be used for other programmes too. It is an invaluable asset for countering misinformation in health, immunization, and other programmes for the well-being of children,” said Shahzad.

While there has been tremendous progress in getting the social listening and misinformation alert systems up and running, there is always more to do. DCE is now focused on strengthening local misinformation response teams while continuing to engage online communities through digital volunteers.

For Gulzar Ahmed Khan, a 28-year-old polio social mobilizer in Pakistan, tracking and addressing polio misinformation is more important than ever.

“Where I work, people have poor understanding of health matters, especially around vaccines. They fear vaccines, they fear us, the polio workers. I explain to them: I’m here for you, for the health and safety of your children. I’m here despite the intense heat and the biting cold. When you refuse to vaccinate, it is the children who will suffer the most. My only motivation is that children and families are spared the suffering of polio,” says Khan.