Global leaders and stakeholders have been unanimously declaring their solidarity to achieving a lasting world free of all forms of polioviruses.

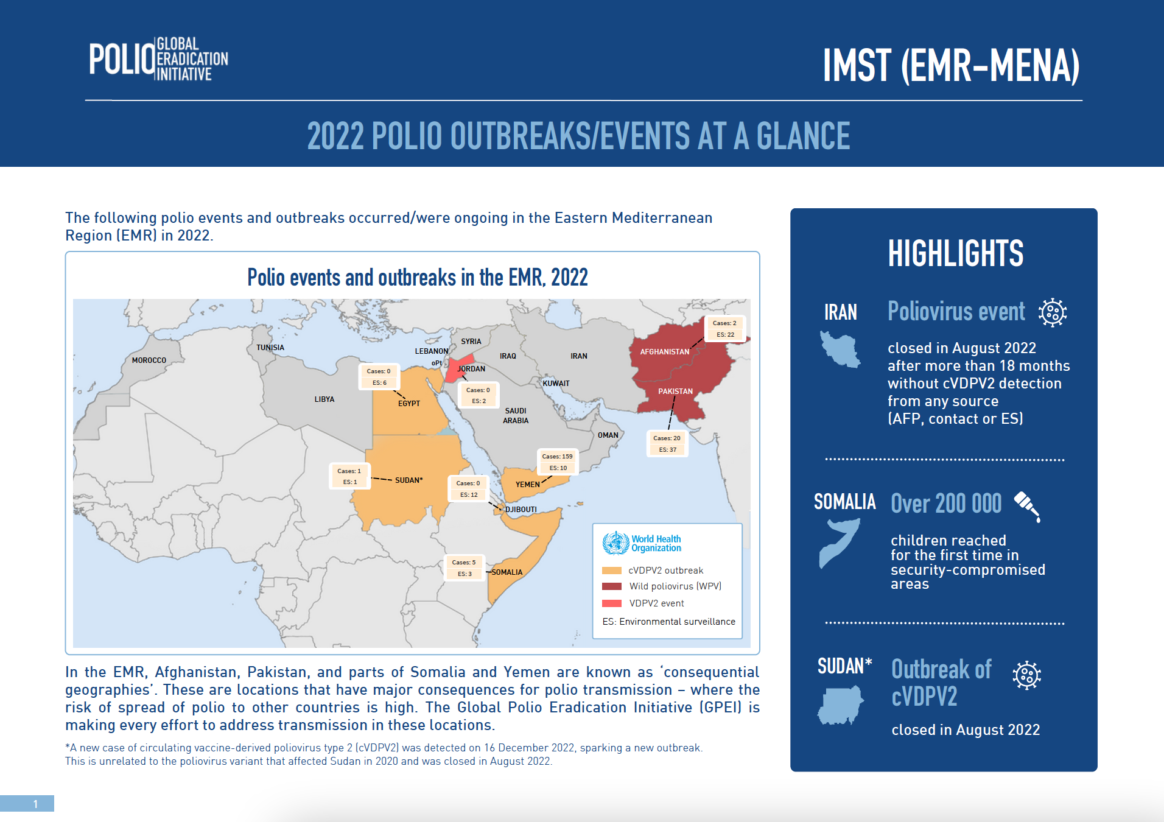

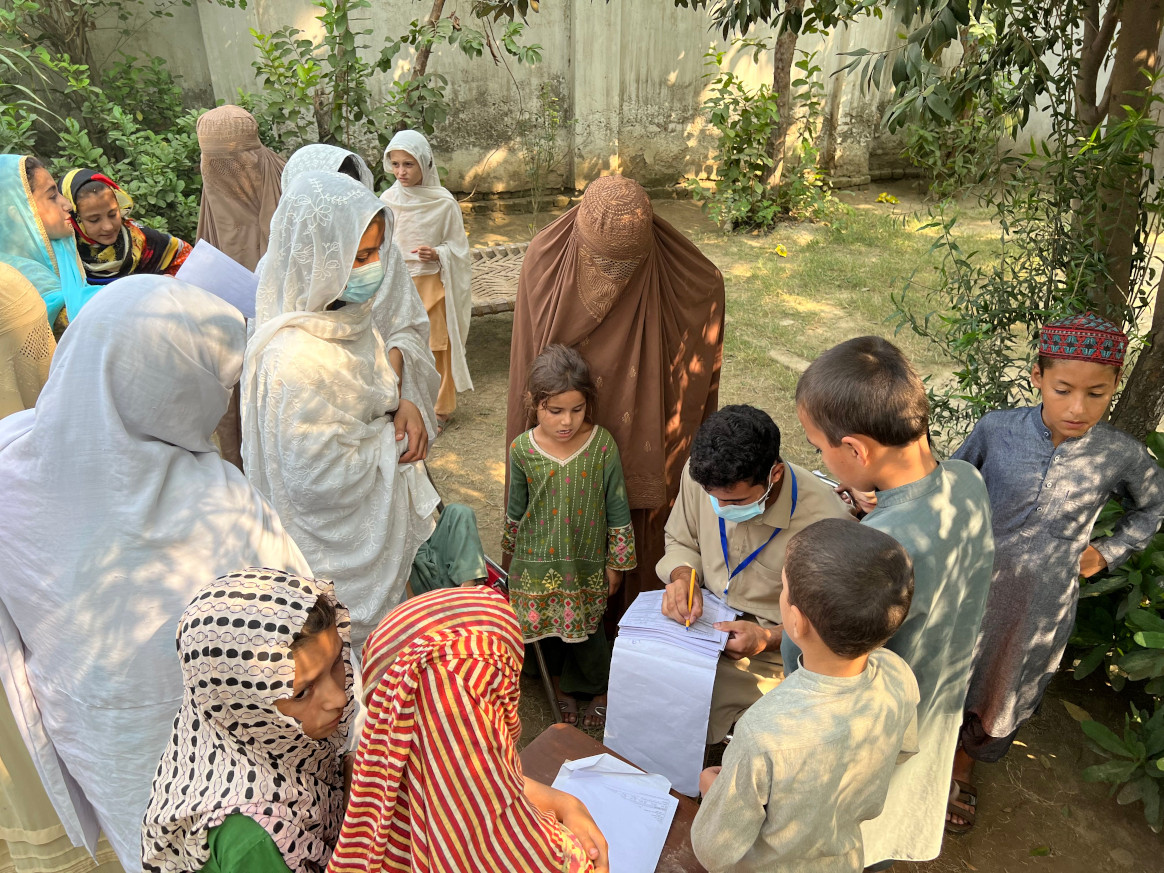

Convening this week at the World Health Assembly in Geneva, Switzerland, Ministers of Health from around the globe evaluated the unique epidemiological opportunity which currently exists, in particular in eradicating all remaining chains of endemic wild poliovirus in a handful of districts of just two countries – Pakistan and Afghanistan. As a record number of Member States and civil society partners took to the floor, key to success, all experts agreed, must be on adapting operations and reaching remaining un- or under-immunized children in just seven subnational most consequential geographies, with collectively account for 90% of all new polio cases, including in a gender-equitable and integrated manner. To ensure lasting success, delegates urged country-specific solutions for polio transition. In response to both a wild poliovirus outbreak in south-eastern Africa and multi-country circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus outbreaks, extraordinary special sessions were led by WHO and its Regional Office for Africa between affected Member States and partners, to discuss concrete steps to stopping all outbreaks affecting the Region by end of year.

The World Health Assembly comes on the heels of last week’s G7 Leaders and G7 Health Ministers meetings in Japan, where both meetings highlighted the urgent need to ensure a world free of polio can be rapidly achieved. Next week, Rotarians from around the world are convening at the Rotary International Convention in Melbourne, Australia, to ensure civil society support for the effort will go hand-in-hand with public sector engagement.

Speaking on behalf of both Pakistan and the entire Eastern Mediterranean, Mr A.Q. Patel, Pakistan Federal Minister for National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination, said: “We are in the final leg of eradication and we are doing everything we have to do to achieve success. The virus is restricted to its smallest-ever geographical footprint, and the (polio) programmes in both Pakistan and Afghanistan continue to vastly expand their hunt for the virus and mount robust campaigns to reach all children, not just with polio vaccine, but indeed other antigens as well. We could not have come this far without the strong support and goodwill of all Member States, however there is still more to be done at the heart of all our work, and for the future of all generations of children. We need continued and sustained financial and political support from all Member States and partners, in order to give every child, no matter where they live, the promise of a polio-free world.”

H.E. Dr Hanan Mohammad Al-Kuwari, Minister of Public Health of Qatar, and Co-Chair of the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Subcommittee for Polio Eradication and Outbreaks, commented: “In our Region, we have made significant progress in both containing the spread of wild poliovirus and closing outbreaks of vaccine variant polio. Afghanistan and Pakistan have restricted the virus to the smallest geographical footprint in history and are now doubling up efforts to fully interrupt the remaining transmission. The engines fueling this progress are manifold, but the two most powerful, and the two I truly believe will get us across the line, are improved immunity and better surveillance. We are reaching and vaccinating more children, more often, and we are using the most sensitive and robust surveillance measures in history to ensure that if the virus is there, we are not missing it. Excellencies, partners and colleagues, I ask this as clearly as I can: Stay the course. Dig deep to do what needs to be done. Stand with us and be part of history.”

Noting the global commitments being made, Jean-Luc Perrin, Rotary International’s Representative to the United Nations in Geneva, told the global health community at the Assembly: “Polio eradication is a rare example of enduring, truly global collaboration toward a goal whose achievement will benefit all nations in perpetuity, while contributing toward broader global health priorities. We cannot take progress or possible victory for granted. Let us make collective history and End Polio Now!”

In conclusion: global leaders continue to note the very real window of opportunity for success this year, but that this window will not remain open for long. The virus will again gain in strength. Only collective and global collaboration will result in ultimate success, and delegates and leaders urge all stakeholders to keep the focus firmly on one overriding objective: reaching remaining un- or under-vaccinated children in the most consequential geographies. A collective responsibility, but if achieved, will result in success in 2023.

Additional quotes from the World Health Assembly:

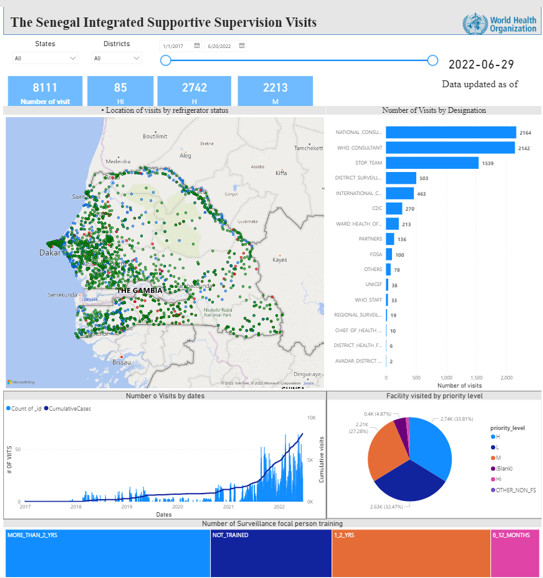

“WHO and our partners remain steadfastly committed to finishing the job of consigning polio to history. Last year, three million children previously inaccessible in Afghanistan received polio vaccines for the first time. And in October, donors pledged US$2.6 billion to support the push for eradication. At the same time, as part of the polio transition, more than 50 countries have integrated polio assets to support immunization, disease detection and emergency response. We must make sure that the significant investments in polio eradication do not die with polio, but are used to build the health systems to deliver the services that these communities so badly need.”- Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General, World Health Organization

“Wild poliovirus transmission has been cornered to the smallest ever geographic locations in the Eastern Region of Afghanistan and seven districts in southern part of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in Pakistan. However, the last 100-metre dash presents its own challenges and we must do all we can to achieve success.” Dr Hamid Jafari, Director for Polio Eradication for the Eastern Mediterranean, on behalf of Dr Ahmed Al-Mandhari, Regional Director, World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Region

“The African Region, which was certified free of wild poliovirus in 2020, has set itself the objective of stopping the transmission of all types of 2 polioviruses by the end of 2023 and integrating polio assets into activities that strengthen broader disease surveillance. It is also deploying integrated public health teams to respond to other emergencies, building on experiences from past poliovirus outbreaks and leveraging the polio network and infrastructure for response activities.” – Delegation of Burkina Faso, speaking on behalf of the entire African Region.