On March 21, Bangladesh introduced both the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) and the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) into its routine immunization system in an official ceremony at Shishu children’s hospital in Dhaka. Thousands of people - from government officials to doctors to health workers - have worked tirelessly in the journey from the preparatory work before the launch to reaching every child with the new vaccines.

By introducing IPV and PCV, Bangladesh now protects children against 10 diseases with 11 vaccines. Easily recognisable from the rapid breathing that every parent dreads, pneumonia is the cause of 22 % of the deaths of children under five in the country. PCV will therefore benefit over 3 million children. While polio hasn’t been seen in the country since 2006, children are still vulnerable to the virus while it circulates in other countries in the region, such as Pakistan. By introducing one dose of IPV into routine immunization, the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) in Bangladesh is boosting protection against polio, and moving towards the globally coordinated switch from trivalent to bivalent oral polio vaccine in 2016.

Bangladesh is a low income country with an incredibly large birth cohort. Despite this, the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) reaches over 92% of children with DTP3, a key indicator of immunization programme performance (WHO/UNICEF estimates, 2013). Expanding coverage in urban areas is the biggest challenge in Bangladesh, with ever growing slums at one end of the scale, and high-rise buildings inaccessible to health workers at the other.

A high level of ownership provides the essential momentum behind a vaccine launch. ‘It should not be that I am able to vaccinate my own children, but that all the children of Bangladesh are not protected. When all the children of Bangladesh are vaccinated, only then can I become the perfect father. It is my duty,’ says Dr Abdur Rahim, Project Manager of the EPI.

'When a vaccine is introduced, the entire system is strengthened,' says Dr Paranietharan, Head of WHO Country Office in Bangladesh.'There are benefits at all levels, from supply chain and storage, to information systems strengthening, to training for health workers, which is an opportunity to motivate and engage.' The health workers involved in the process at all levels are the ones who make the entire system operate.

Paediatricians played an important role in the introduction of IPV and PCV, because they are well respected as a source of information for protecting the health of children across the country. Dr Probir Kumar Sarker from Shishu Children’s Hospital in Dhaka explains that pneumococcal pneumonia is one of the biggest fears of parents, and that both of the new vaccines are eagerly awaited. ‘Every time, every minute, we are vulnerable to polio,’ he adds. ‘We can’t control migration so there is always a risk. But now we have IPV in our hands we will win the game. We are very close to our dream of complete global eradication.’

With political will and strong advocates in place, detailed planning is the next essential step for any introduction. Chief Health Officer Brigadier General (Dr) Md. Mahbubur Rahman is managing the introduction for the 5 zones and 57 wards contained in the South City Corporation in Dhaka. Despite challenges such as rapidly growing slums where sanitation and health systems are weaker, Brigadier General (Dr) Md. Mahbubur Rahman explains that the strength of the EPI made the introduction go smoothly. ‘People are always excited to receive a new vaccine. They will even delay going for vaccinations in order to receive the new ones,’ he says.

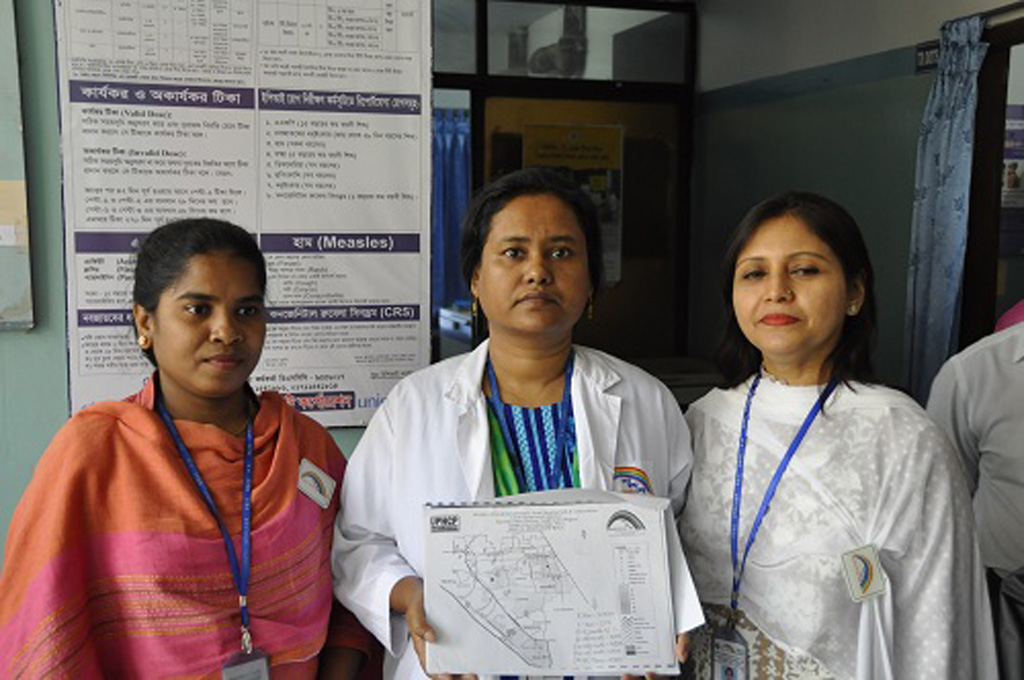

At the Foridabad vaccine distribution site and primary healthcare centre, Dr Fatima Johara (centre) knows the number of children born in the area, and when they will need every vaccine, including IPV and PCV. She proudly holds a micro plan for the nearby Bank Colony slum, into which she has fed the exact numbers of the new vaccines that they will need for the 11 EPI clinics held every month that are supplied from this site. These numbers feed up into plans at the national level, helping the government and UNICEF to ensure a reliable vaccine supply.

In the South City Corporation alone, Dr Hasina Ahmed (right) is one of 1,100 health workers who have attended two days of training, one on PCV and one on IPV. ‘I settled in the health care centre in which I work now because I was brought up in this area; I am a child of these streets,’ she says. ‘I have been to many training sessions over the years but I learn new things every time. Every year technology is changing, and the schedule for when we administer each vaccine changes. The most common disease I see in children of 10 to 15 months is pneumonia, so I hope this introduction will do tremendous, life-saving things for Bangladesh’s children.’

Mr Golam Mostofa is a technician at the central vaccine store in Dhaka. ‘My job is very important. It is not easy to pack and unpack vaccines safely, and to transport them where they need to go,’ he says. The cold chain that spreads across Bangladesh had to be assessed for capacity in advance of the introduction, and was found strong enough to incorporate the two new vaccines. The store where Mr Mostofa works at the EPI headquarters was recently expanded to accommodate all the necessary vaccines and supplies for the whole country.

The cold chain takes many forms in order to reach children across the country. From Foridabad, Dr Luna Unnekamrun (left) takes vaccines by rickshaw to satellite clinics like the one in Bank Colony slum. The dual introduction means that people like Luna will have to incorporate two extra vaccines into their work schedule. The extra time that it will take to talk to parents about the new vaccines and to administer them is a significant workload, but health workers in Bangladesh are happy to be able to offer parents more protection for their children.

The importance of the training received by health workers like Luna is demonstrated as she speaks to parents at the Bank Colony slum clinic. Answering questions and explaining why IPV and PCV are important for babies will play a key part of her job in the months to come. The energy and resources that EPI in Bangladesh puts into communications and training is one of the reasons for the high level of trust and demand for vaccines in the country.

The political will, extensive advocacy from paediatricians, politicians and health workers, training sessions, cold chain evaluations and planning that have gone into the dual introduction culminate in millions of children who will now grow up protected from 10 diseases. The black soot mark on the foreheads of so many babies in the clinics of Bangladesh is one of the traditions parents rely on to ensure their child is safe, wherever they go. While the two extra vaccines leave no outer trace, they offer invisible, internal layers of protection, brightening the future of every single child who receives them. This is the incredible legacy from all those who work behind the scenes to make a vaccine introduction possible.