The border between Pakistan and Afghanistan is no barrier to the poliovirus. Close cultural and linguistic ties connect the two countries. Populations move fluidly across these borders. Each year, the virus moves with them.

Afghanistan and Pakistan have seen significant progress in the last 18 months in their efforts to stop polio. But both countries have been close before, and have been thwarted: the virus has found pockets of unvaccinated children where it can hide, regroup, and stage a comeback. Despite historically low levels of polio over the last few months, cases of paralysis and positive samples found through environmental surveillance show us that the virus has not yet been stopped.

A new approach

Armed with this knowledge, Pakistan and Afghanistan have taken a new approach. Since June 2015, the two have been coordinating major programme activities, as success in one country depends on success in the other. Monthly polio immunization campaigns have been synchronized so that no child on either side of the border can fall through the cracks, the Emergency Operations Centres (EOCs) of each country – which house the government and partners of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative to coordinate eradication activities – interact with one another on a weekly basis, and the highest level political and administrative leadership meet face to face every six months, to resolve challenges and to develop plans to address the remaining hurdles.

A common communications strategy has synchronized messaging at the border and – with radio being the main source of news for 70% of Afghans and 50% of Pakistanis in border areas – the programme has coordinated radio programming on the leading border channels, producing weekly health shows and using popular soap operas to create Pashto-language programming on polio and children’s health.

This innovative approach is paying dividends. The polio eradication programmes in both countries are working closely together to coordinate vaccination campaigns, surveillance, and to track population movements.

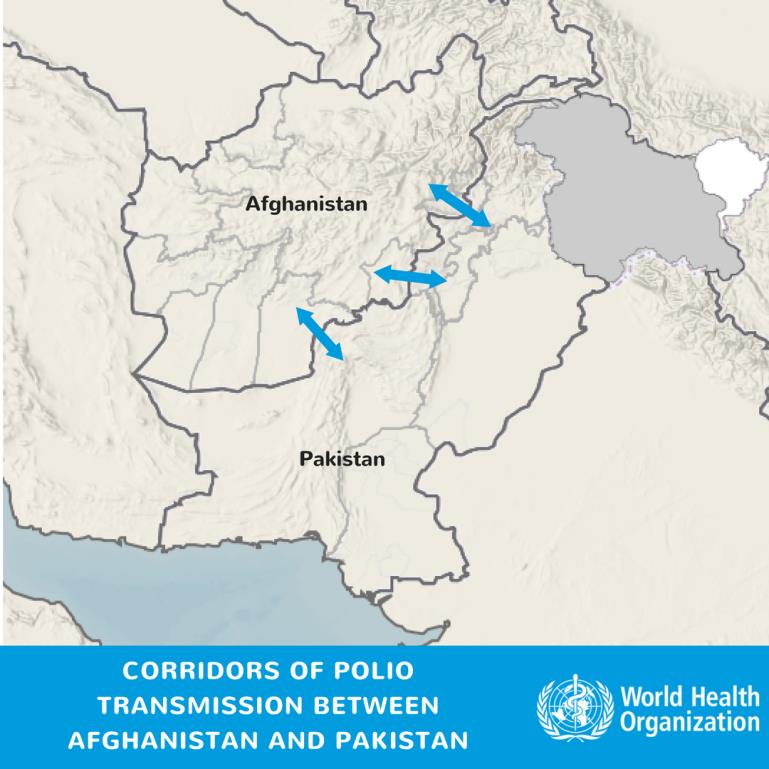

The three ‘corridors’ of polio transmission

Three ‘corridors’ are serving to allow the virus to travel with population movements between countries: via the Torkham border crossing from Peshawar and Khyber in Pakistan to Nangarhar, Kunar and Laghman in east Afghanistan, and via the Friendship Gate border crossing from Pakistan’s Quetta Block to the Greater Kandahar area in south Afghanistan. Population immunity in these transmission corridors have been gradually improving in the last year, shown by the vaccination status of non-polio AFP cases.

Wild polio increasingly seems to be travelling down a central corridor between southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas in Pakistan travelling across rugged, smaller border crossings to Paktika, Paktia and Khost provinces in the south east of Afghanistan.

Mobile populations

At the most recent Inter-Country Coordination Meeting in Islamabad, Pakistan, the Afghanistan National EOC Director underscored the importance of reaching and vaccinating populations on the move, whether at formal or informal locations.

While Torkham in the northwest and Friendship Gate in the south are the main border crossing points between the reservoirs – with more than one million children under 5 crossing these points each year – the smaller informal crossings are considerably more challenging to reach and vaccinate children.

Pakistan and Afghanistan are working to strengthen coordination on the communities moving through these locations, to ensure that all children under 5 are vaccinated wherever they are. The programmes are strengthening their disease surveillance at community level, mapping out mobile groups and ensuring they’re included in immunization microplans, and working with leaders and influential figures to understand their movements better.

Stronger together

The new polio cases in the central corridor have reinforced the idea that neither Pakistan nor Afghanistan can eradicate polio alone, with the virus travelling between the two. At the Islamabad meeting, the National EOC coordinator for Pakistan highlighted the fact that neither programme was where it intended to be by this time in 2016, and these strategies tailored to addressing specific challenges were essential to end the virus for good.

The significant improvements in the programme quality in the southern and eastern corridors can be attributed to a relentless focus on improving campaign quality and the innovative approach of the two countries working as one team across the border.

Pakistan and Afghanistan are learning from the programme’s experiences in other countries. If this progress can be maintained in the traditional corridors between the long-time polio reservoirs, and the programme can move quickly to rapidly increase immunity in the new, central corridor, the programme has the opportunity to strike out polio in two countries with one blow, working together to ensure that no poliovirus can find a hiding place along the porous border between them.

| The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) is highlighting the innovations that are helping to bring us closer to a polio-free world. Find out about other new approaches driving the polio eradication efforts by reading more in the Innovation Series. |