Eradicating polio needs constant vigilance to vaccinate every last child and find every last virus. Eradicating polio needs constant vigilance to vaccinate every last child and find every last virus. The sobering news that two children were paralysed by wild poliovirus in Nigeria in 2016, two years since the last case was found, emphasises the importance of keeping efforts at full pelt to protect children. From vaccination to surveillance to maintaining momentum, this global effort takes tireless efforts from thousands of people.

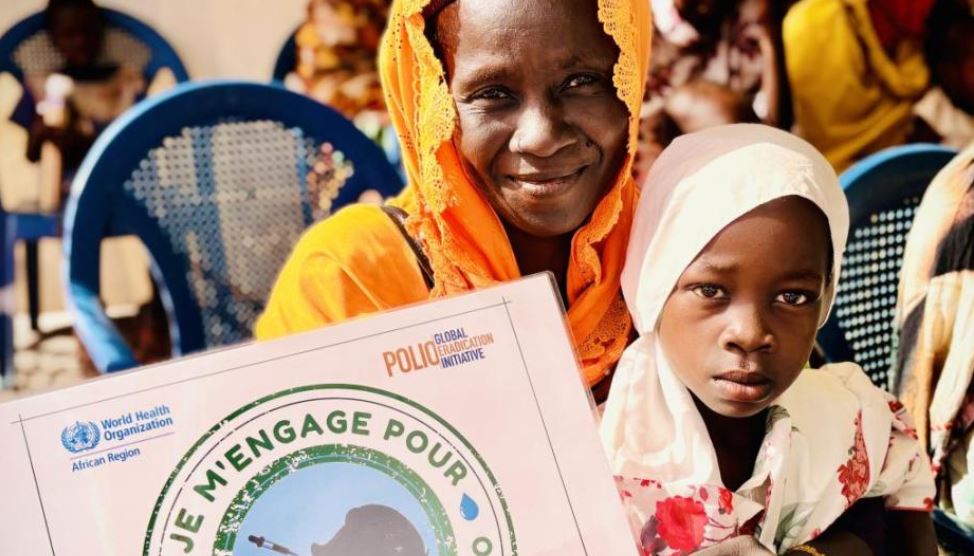

While polio exists anywhere in the world, children everywhere remain at risk. Vaccination campaigns bring the oral polio vaccine to children in cities, hard-to-reach villages and everywhere in between across the continent no matter how challenging so that they can be protected against this incurable disease. As many as 600,000 children across north eastern Nigeria remain inaccessible to polio vaccinators due to insecurity, presenting a very real obstacle to polio eradication efforts.

The polio eradication programme is also supporting routine immunization to ensure that children are protected systematically and reliably against polio and other vaccine preventable diseases. The inactivated polio vaccine is also being introduced into many routine immunization systems to boost protection.

It is essential that families and communities understand the importance of getting their children vaccinated. Local men and women, most often volunteers, continue to go door to door spreading the word.

Across the continent, a surveillance network of thousands of healthcare workers, community leaders, traditional healers, teachers and parents are on the alert for signs of paralysis that could be caused by polio. Every single case needs to be reported and tested for polio so that the virus can be stopped as soon as possible if it returns.

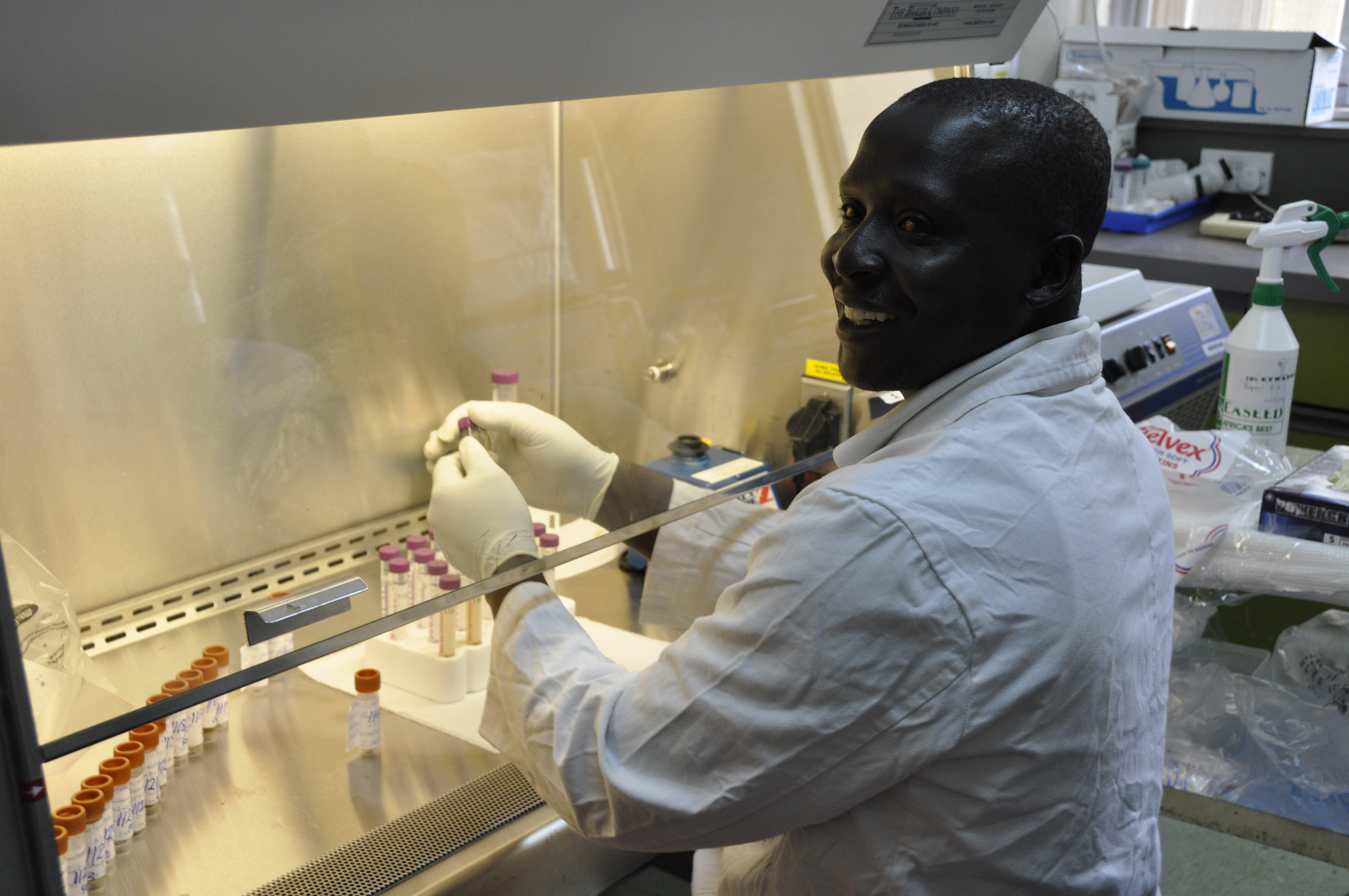

As well as looking for cases of paralysis, the virus is being sought in waterways and sewage systems. By testing water samples, the virus can be traced before it causes paralysis, giving governments and partners of the GPEI a clearer understanding of where children are vulnerable so that they can be protected.

As well as working to stop transmission in Nigeria, every country must be prepared to respond to outbreaks of poliovirus, including vaccine derived polioviruses. By making detailed micro-plans mapping out communities, vaccination campaigns are more likely to leave no child unreached. High levels of immunity mean the poliovirus wouldn’t be able to cause paralysis, even if it were to return to Africa.

Once wild polio has been eradicated globally, the only place it will continue to exist will be in laboratories or vaccine manufacturing facilities. Therefore it is essential for all poliovirus stocks to be safely and securely contained to minimise this risk.

The polio eradication infrastructure supports many other health needs, such as routine immunization, maternal care, and the delivery of vitamin A and deworming tablets. As we move closer to possibly certifying the region polio-free, the GPEI will begin to ramp down. Countries across Africa are planning for how to maintain polio-essential functions and how to use some of the polio eradication staff and infrastructure to help meet other health goals in the future.

From politicians such as President Buhari of Nigeria to local government to donors and health workers, maintaining the drive to continue with all this essential work is crucial. Only with commitment from the global to the local level can we secure a polio-free world for all future generations and assign polio to the history books.