On a wintery November day, vaccinators across Afghanistan wrapped up warm, checked that they had facemasks and hand sanitizer, and headed out into the cold morning. Their mission? To reach 9.9 million children with polio vaccines, before snowfall blocked their way.

From valleys to muddy lanes, we look at some of the environments where vaccinators work, as well as some of the key challenges that have made 2020 one of the toughest years for polio eradicators.

Panjshir province

For some vaccinators, the first snows had already arrived. At the top of the Panjshir valley, Ziaullah and Nawid Ahmad started their day at 7am.

“We walked six hours to Sar-e Tangi and back to take polio drops to the last houses in the valley”, said Ziaullah. The mountainous roads in this area are impassable by car, so vaccinators walk many kilometers to the most remote villages. Sar-e Tangi means ‘top narrow edge’, and the view during the long winter is of snowy peaks.

A few kilometers from Sar-e Tangi, father Arsalan Khan was proud to have protected his own and other children in the extended family with polio drops. He said, “I ensure all the children in the family are vaccinated during each round the drops were offered and of course I will keep vaccinating them each time the vaccinators visit our village”.

Khan continued, “The vaccinators walk long distances across the mountain slopes to our villages, sometimes during harsh weather conditions, to bring polio drops to our doors.”

“Thanks to the people and countries that support the vaccination campaigns and make it possible for the drops to reach our doorsteps.”

Badakhshan province

In Badakhstan, Mr. Azizullah had COVID-19 safety measures on his mind. Like all vaccinators working for the polio programme, he had been trained on how to safely deliver polio drops during the pandemic. The temperature was below zero, with the first snow on the ground, as Mr. Azizullah walked through the rugged terrain from home to home, ensuring to wear his mask and regularly sanitize his hands.

Mr. Abdul Basit and Misbahuddin, volunteers in nearby Aab Barik village said, “It is cold and walking through muddy lanes is not easy, but we have to do our job. There was one case of polio in Badakhshan so that means there is probably virus circulation and we have to stop that”.

Herat Province

Mr. Abdullah, a university lecturer observing vaccination activities in Herat, said, “I believe a vaccinator’s job is more important than mine. I really appreciate their work and appreciate the international community for making the polio immunization operations possible in Afghanistan with their financial support.”

“I believe that all these efforts will be fruitful, hopefully soon, and we will get rid of the virus in our country”.

The November campaign was particularly aimed at boosting the immunity of unvaccinated children, and children who have not received their full vaccine doses. Many children have missed out on polio vaccines and other routine immunizations due to a pause in vaccination activities in the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Health workers are now racing against time to protect the youngest children from the poliovirus.

Ms. Sitara, mother of Yasameen, who was wrapped up warm against the elements, said, “I am very happy to be able to immunize my daughter and protect her against polio”.

Jalalabad Province

In the east region of Afghanistan, 8,530 volunteers, 160 district coordinators and 786 cluster supervisors were hard at work, aiming to reach as many children as possible during the campaign.

Dr. Akram Hussain, Polio Eradication Initiative Team Lead for WHO in the region explained, “We were not able to do house to house campaigns in some parts of the region. As a result many children were missed during the October vaccination campaigns”.

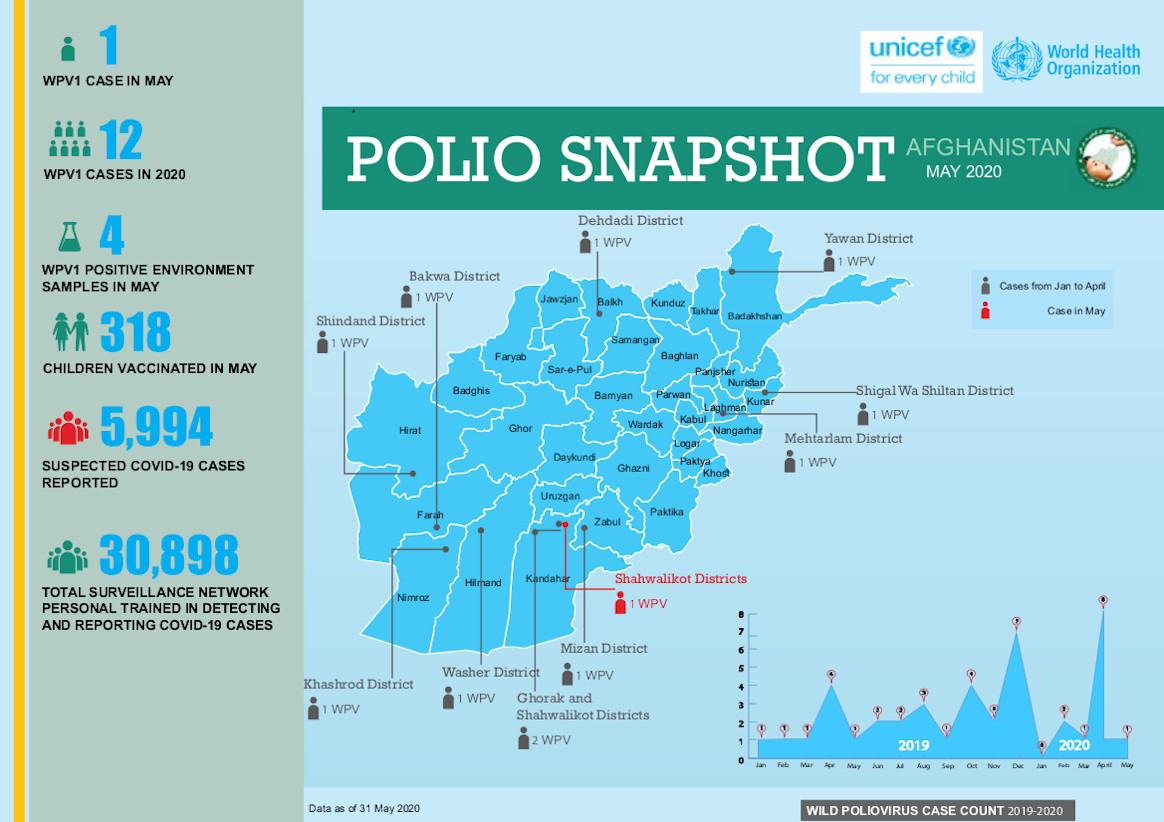

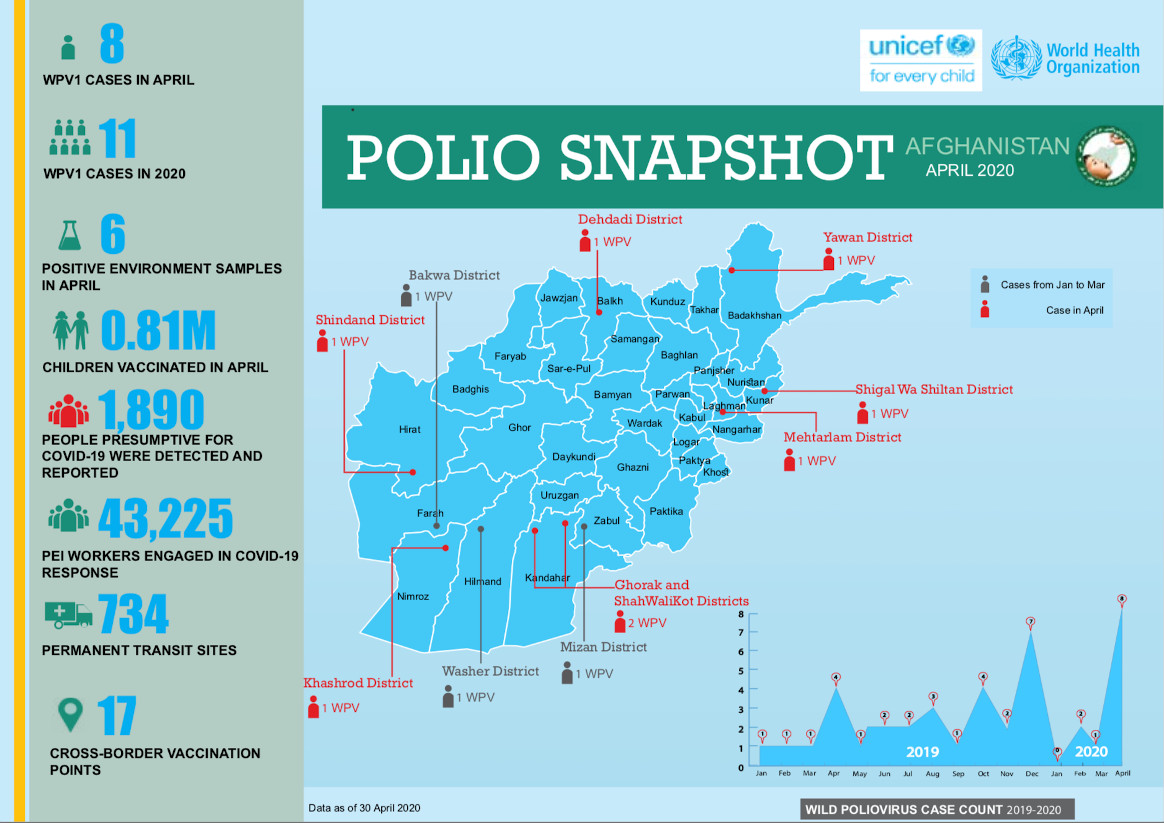

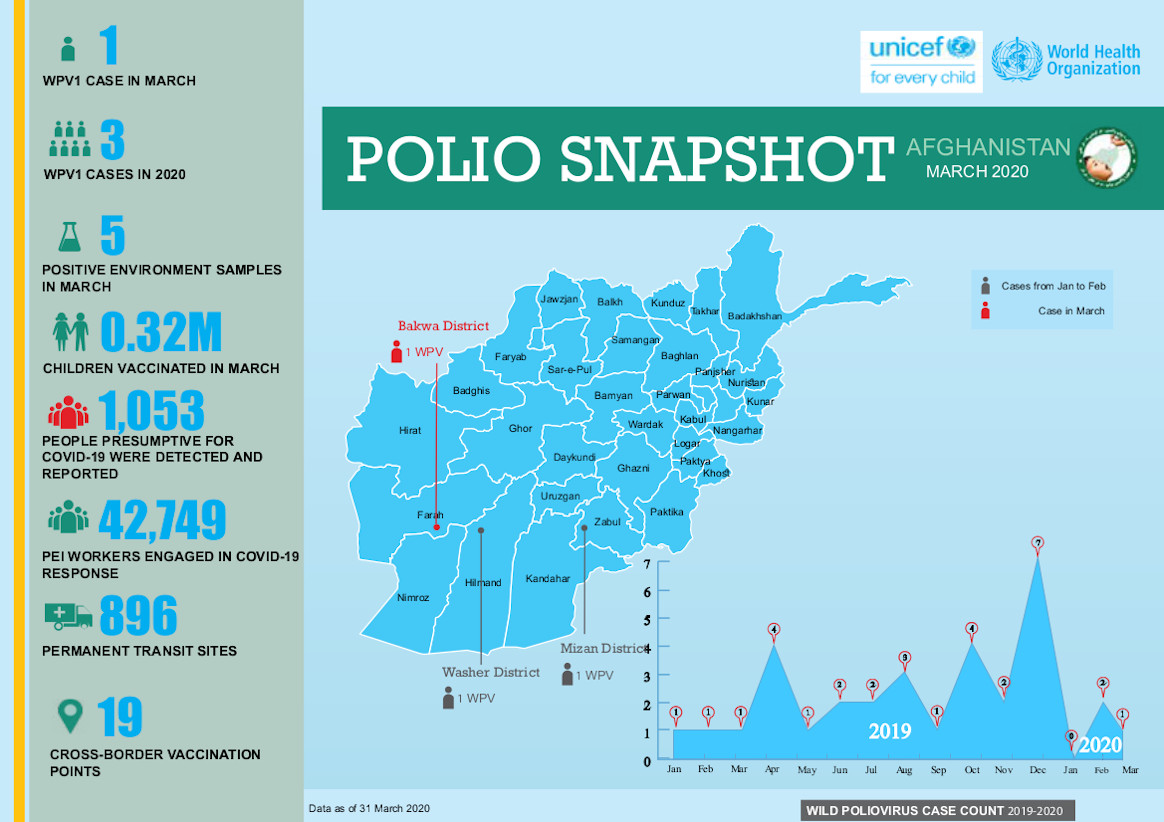

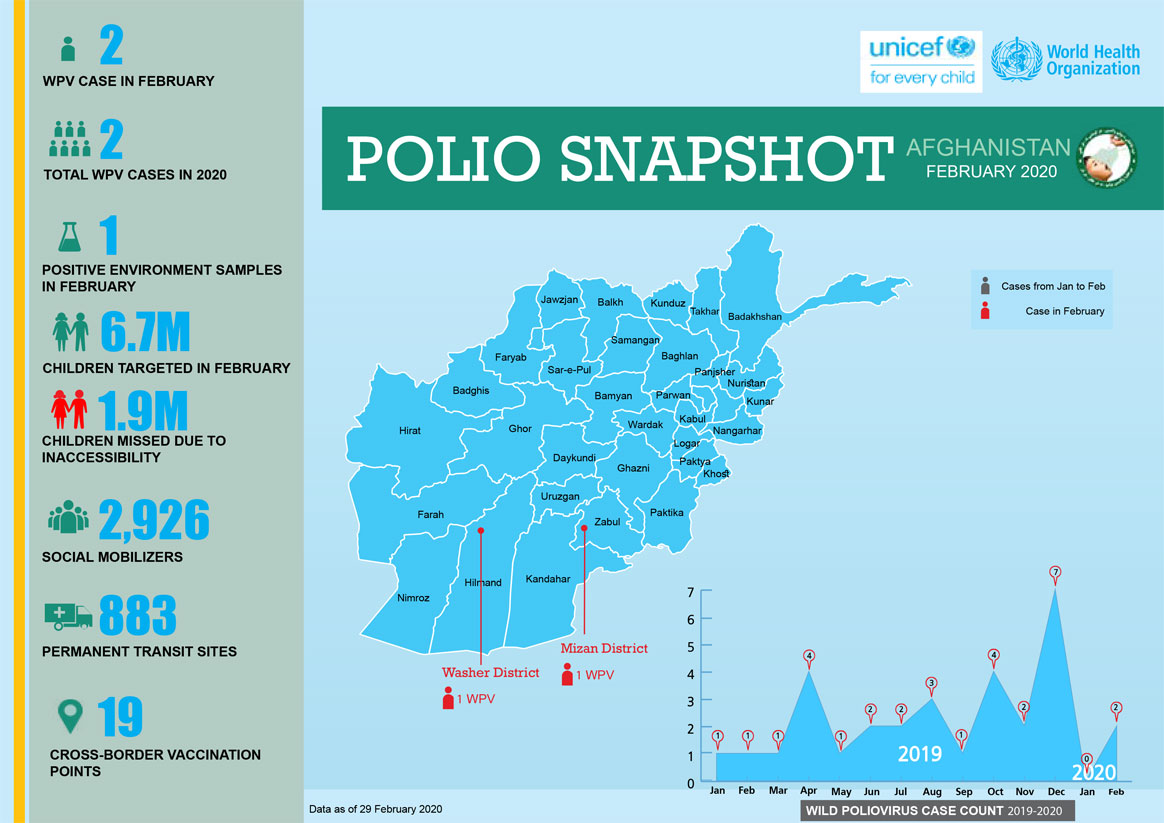

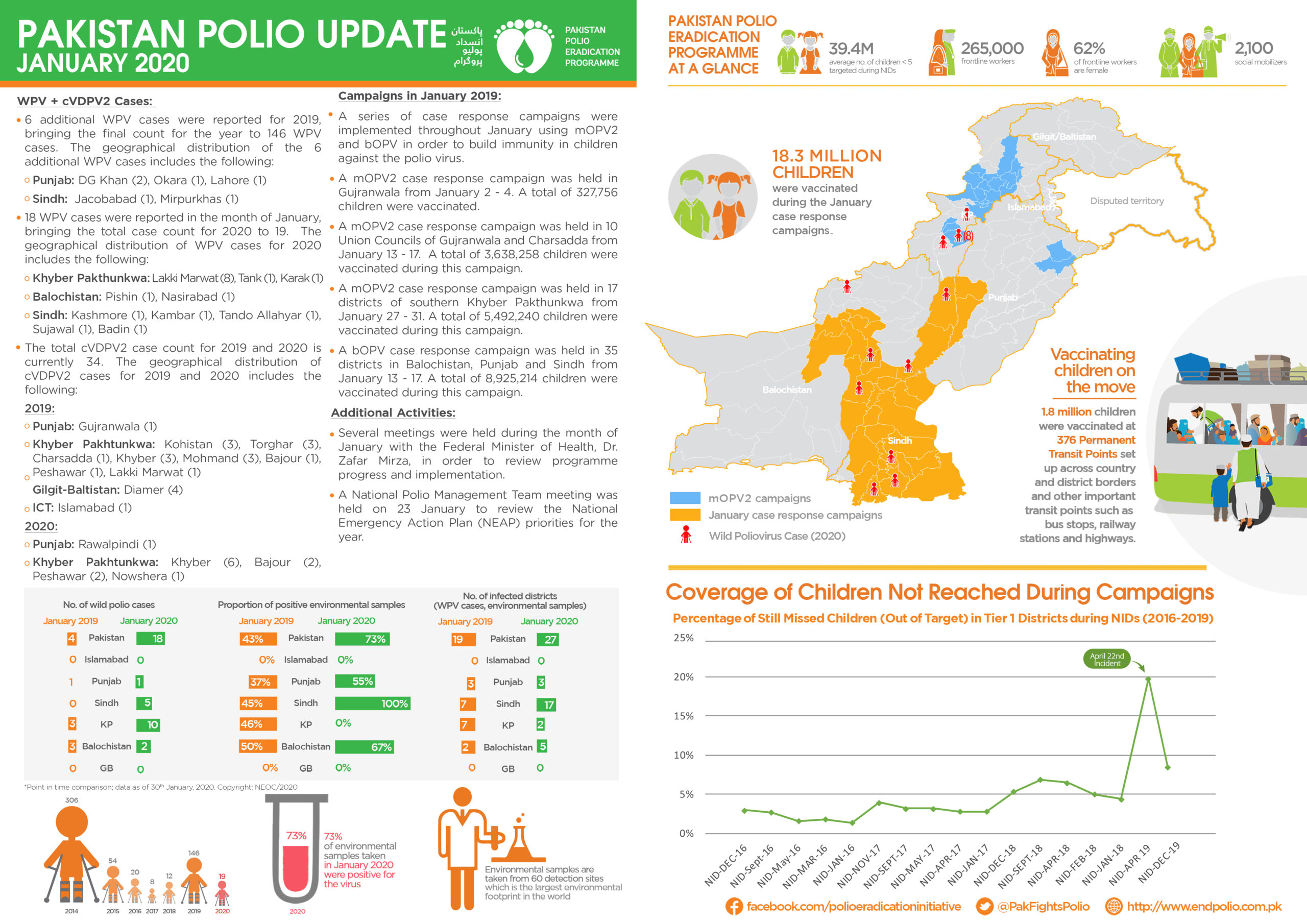

Despite the best efforts of vaccinators, in October, 3.4 million children nationwide missed vaccines due to factors including insecurity, the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine mistrust. The year 2020 has seen a significant rise in polio cases and detection of the virus in the environment, and the disease is present in almost all provinces.

The programme is aiming to reach more children and tackle virus spread next year. Activities include targeted campaigns in high risk districts, collaborating with the religious scholars from the Islamic Advisory Group to encourage vaccine uptake and communicating more effectively with communities.

The incredible contributions of the polio programme to COVID-19 response are testimony to the agility and adaptability of Afghanistan’s programme in the most difficult circumstances. Many hope that lessons learnt from this experience can be applied to achieving the eradication goal.

Ending polio requires everyone – including polio personnel, communities, parents, governments and stakeholders – to commit to overcoming challenges. As the weather turns colder and snow continues to fall, many are looking ahead to what 2021 holds for polio eradication in Afghanistan.