In December 2023, novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2) made history by becoming the first vaccine to move from use under a WHO Emergency Use Listing (EUL) recommendation to full licensure and WHO prequalification. We catch up with Chair of the GPEI’s nOPV Working Group Dr. Ananda S. Bandyopadhyay, from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Chair of GPEI’s Vaccine Supply Group Ann Ottosen, from UNICEF’s Supply Division, and WHO African Region’s Polio Eradication Coordinator Jamal Ahmad to discuss how things have changed in terms of nOPV2’s use, and next steps for this innovative tool.

Welcome Ann and Jamal, and welcome back, Ananda. A lot has happened in the past three years since nOPV2 was first used in the field under EUL. Prequalification is a big milestone. Tell us about this achievement.

Ananda

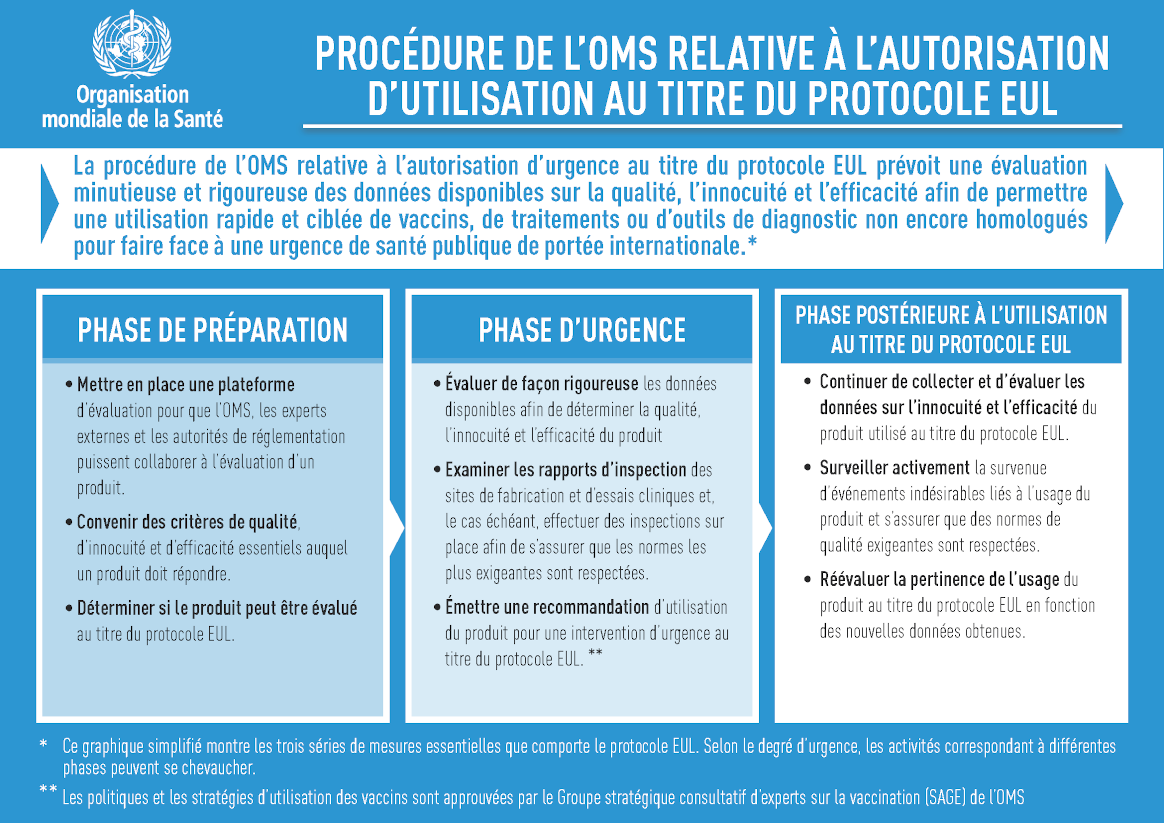

Hello – good to be speaking with you again. Yes, the WHO Prequalification (PQ) of nOPV2 is a major milestone for global public health, as this is the first example of a vaccine making the transition from EUL use to PQ. In fact, nOPV2 was the first vaccine to achieve an EUL authorization – the same process that has since been used to accelerate access to thirteen COVID-19 vaccines – so another ‘first’ for public health there.

When I look back at this journey, I feel immensely thankful to so many partners and collaborators across the world who joined this effort since it began back in 2011. Since then, we’ve gone from idea generation to pre-clinical and clinical development, to manufacturing at-scale, and then to EUL authorization for field use in November 2020. Over the past three years, there’s been rollout at a massive scale, with nearly 1 billion doses administered across 35 countries by the time full licensure from Indonesian regulatory authority (BPOM) and PQ was issued in December 2023. This truly is an example of scientific innovation being translated into global health action through a worldwide collaborative effort.

What does nOPV2’s prequalification mean for countries? What are some of the benefits of the vaccine being PQ’d?

Jamal

The prequalification of nOPV2 represents a big advancement in the global fight against polio, particularly in managing and mitigating outbreaks of type 2 variant poliovirus (cVDPV2), the most prevalent form of the variant virus. Almost 95% of the vaccine used to date has been in African countries where there is the biggest burden of cVDPV2 outbreaks.

Throughout its use under EUL, GPEI and countries have rigorously collected and analysed data on the vaccine’s performance and PQ signals the final, formal endorsement of nOPV2’s safety and efficacy. This has several key benefits, including a streamlined process for countries that wish to use it. Ultimately, PQ facilitates a quicker response to cVDPV2 outbreaks with a vaccine that has a much lower likelihood of seeding new outbreaks.

Ann

Preparation for use of the vaccine under EUL was a time- and resource-intensive process for both the GPEI and countries. Countries needed to meet several requirements across numerous functional areas to access and use the vaccine, including local approvals, cold chain and vaccine management, surveillance, safety and advocacy, and communications and social mobilization. A readiness verification team of the GPEI would review country performance on these criteria before UNICEF would be authorized to deliver doses from the global stockpile to the country. Now that the vaccine is prequalified, these requirements have been lifted.

Would you say demand for nOPV2 has changed since prequalification?

Ann

nOPV2 is now the preferred tool to stop type 2 variant polio and, because of ongoing outbreaks, demand for the vaccine has unfortunately increased. In addition, since countries no longer must meet the rigorous readiness requirements to use the vaccine that I described above, it is easier and quicker for them to request it.

nOPV2 is accessible through the Global OPV Stockpile – a unique mechanism for the type 2 polio vaccines used in outbreak response, and only following release by the WHO Director-General upon technical review and endorsement of a country application. The number of doses in this stockpile is planned far in advance with the manufacturer based on forecasted demand from the GPEI, and the vaccine in the stockpile is only produced to order as there are no commercial markets for nOPV2 and production lead times are up to a year. Therefore, it is critical to secure enough supplies that the forecasting is correct and production runs smoothly.

Jamal

The demand for nOPV2, particularly in African countries, continues to be high with it being the vaccine of choice when it comes to responding to type 2 variant polio outbreaks. As the program aims to get ahead of the virus with large scale outbreak responses, we hope to see a significant decline in demand for the vaccine in the coming years as outbreaks are closed.

Given the current demand, how are we tracking in terms of supply? From our last conversation, it seemed sufficient at the time but has the situation changed?

Ann

So far, we have been dependent on a sole supplier, which has produced 1.4 billion doses of the vaccine since nOPV2’s field use began in March 2021. This is truly a massive scale up over a short period of time. However, vaccines are biological products, and the manufacturing processes are very sensitive. Since November 2023, due to unexpected delays in maintenance and testing procedures, we are experiencing a disruption in supply with filling of new vaccine temporarily paused. This problem has yet to be resolved and the GPEI is working closely with the manufacturer to identify the root cause, remediate the issue, and restart production as soon as possible.

Since the program had planned an aggressive schedule for large-scale outbreak response activities in Q1 2024, there was an initial need for 330 million doses of the vaccine. However, because of the current supply disruption, the program is prioritizing available nOPV2 to respond to outbreaks in the highest risk areas. With this prioritization, more than 200 million doses have been or will be delivered to countries in Q1 of this year. We are hopeful that more supply will become available in May 2024 to address any postponed activities.

Jamal

The current supply challenges will be a speed bump on the road to ending type 2 variant poliovirus in Africa, however, measures are being taken to address these challenges in the region and reduce their impact on the overall goal of eradication. As Ann touched on, we are adapting our outbreak responses accordingly, with an immediate focus on areas of highest need that pose a risk of international spread and we believe we will remain on track.

Ananda

I would also like to note that when you look across the different vaccines available in global supplies, issues like what we are seeing now with nOPV2 are common. In fact, this is expected given the massive demand for the vaccine and the rapidity with which the scale up and supply readiness steps had to be implemented due to the serious emergency that cVDPV2 outbreaks constitute.

As such, the GPEI has been working to engage an additional manufacturer. While the program remains confident in the current manufacturer’s continued capacity as a supplier of nOPV2, as with any vaccine, having a diversity of suppliers is important to help ensure supply meets demand. This second supplier is expected to begin filling vials with nOPV2 and finalizing the product for shipment by mid-2024, with full production capacity expected by the end of the year. This will help address the current shortage of the vaccine and reduce the risk of supply disruptions in the future.

Some countries, for example Nigeria, are using a lot of nOPV2 but are still battling transmission. What kind of tactics will be taken in these places?

Jamal

Nigeria is a good example of the last mile challenges in the eradication effort. It is a large country with a very large population, which means huge cohorts of vulnerable children. In addition, ongoing challenges like inaccessibility, insecurity and vaccine hesitancy in the country have led to pockets of communities where the traditional methods of reaching children are not as effective.

A multifaceted, tailored approach in these places is therefore essential to get to zero. The program continues to work with local authorities to implement new geospatial technologies to inform outbreak response microplanning, enabling teams to more consistently find and reach missed populations. This, combined with efforts to engage local leaders in the most insecure areas, are helping ensure no child is left unprotected from this devastating, preventable disease. In addition, enhanced surveillance systems and improved cold chain infrastructure will continue to be critical to facilitate rapid alert and responses to potential polio cases.

It is possible for confined transmission of the virus in a small part of the country to find its way to large population centres and lead to massive outbreaks. Therefore, periodic intensified large-scale vaccination and public awareness campaigns, coupled with targeted vaccination drives in high-risk areas with persistent transmission, are also necessary to keep the virus cornered.

Lastly, on nOPV2’s genetic stability. How’s that going? Is it still performing at the same level?

Ananda

After almost three years of large-scale nOPV2 use, all data demonstrates that nOPV2 has about 80% lower risk of seeding new type 2 variant poliovirus outbreaks compared to its predecessor, mOPV2. nOPV2 has proven to be an important tool that will help the program more sustainably stop the virus.

However, the bottom-line remains that the success of nOPV2, like any polio vaccine, depends on the ability to rapidly implement vaccination campaigns in response to outbreaks that reach every child. We are confident that with the help of global, regional and country partners, and most importantly the frontline health workers visiting communities, we will interrupt variant poliovirus transmission once and for all.