KARACHI – The only life Huma Ashraf has known outside her home is of a health worker. That’s what made her step out on September 11, 2023, when she was verifiying microplans in a slum behind a railway track.

Hours later, in a moment that would redefine her life, she was rushing to Karachi’s Jinnah Hospital in an ambulance all by herself, following a train accident.

“It all happened so fast. I had to verify the homes behind the tracks and the only way to get there is crossing the railway track,” she says, recalling that day of the accident with exceptional calm. “The train seemed far away, and I thought I could cross over, but there was a gush of wind and my dupatta was caught in the train.”

In a mere matter of minutes, her life changed as she lost both feet.

The people who witnessed the accident called for an ambulance. With startling presence of mind, she collected the feet in the hope of a surgical reattachment and specified which hospital she wanted to go to.

Hina, her younger sister, is amazed by Huma’s courage that day. Showing the text message she received, she shares how Huma wrote to her with striking clarity. “Pair kat gaye hain, hospital ja rahi hun. Ammi abbu ko mat batana” (Have lost my feet, going to the hospital, don’t tell mom and dad.)

By the time Huma was taken into surgery, nearly five hours later, the damage was irreversible.

Hina worked up the courage to tell their parents about the accident after the surgery. Her mother initially thought Huma’s toes were affected. “I couldn’t fathom the extent of it,” says her mother Rukhsana.

A Legacy of Healing

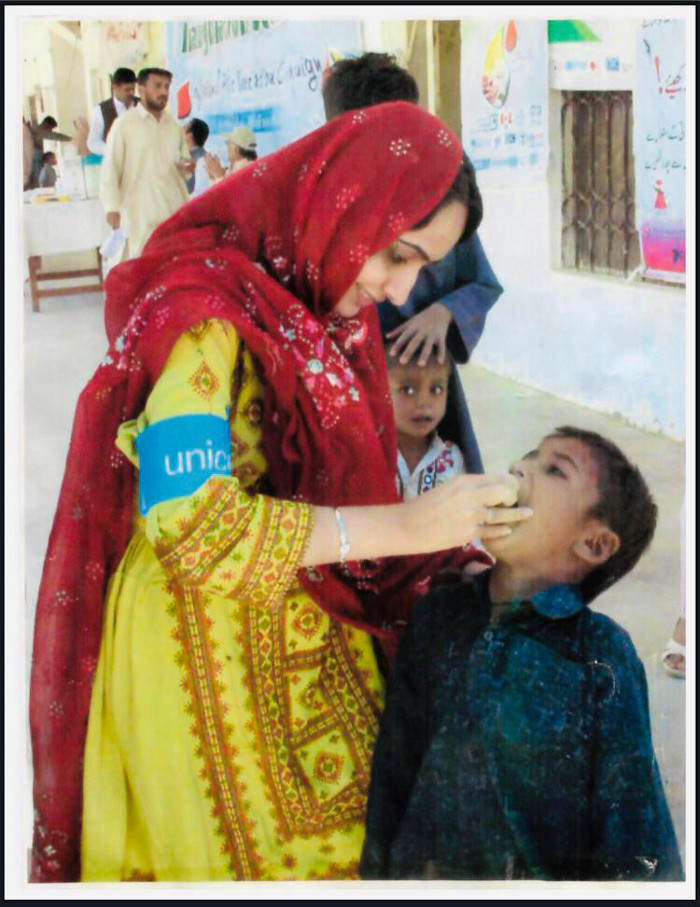

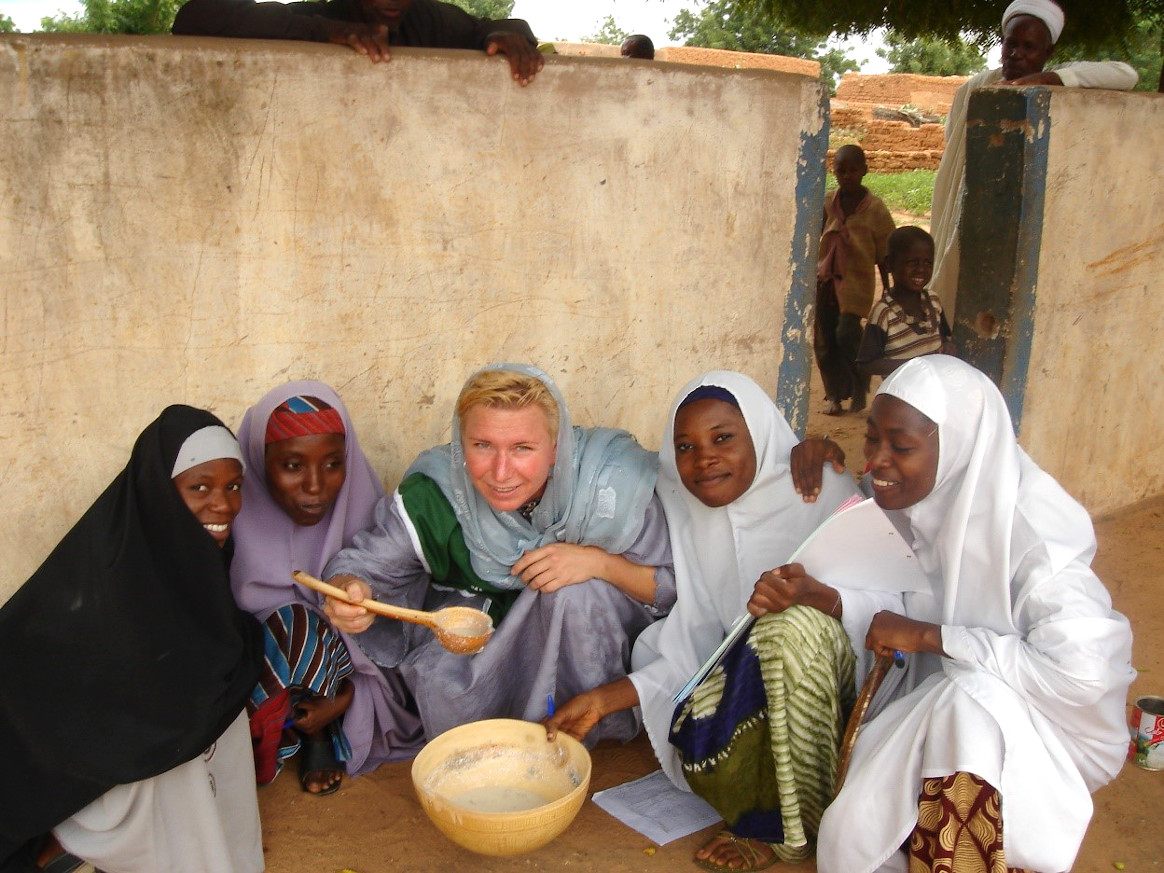

Since Huma was 14, she has known what an aspirin could do, the contraceptives women would seek and that two drops of the oral polio vaccine could protect a child from lifelong, paralytic polio. These were her mother’s teachings. As she grew older, she also learnt how to administer injections. Rukhsana would ask Huma to try injections on her, consistently training her on how to provide basic health services to the community.

Rukhsana, a lady health worker, started working in 1995. As the eldest child, Huma would go along, and the mother-daughter duo would navigate the streets of Karachi, bringing essential healthcare within reach to women and children, and making friends along the way.

All of Rukhsana’s five children have worked for the Polio Eradication Initiative at some point, but it was Huma who stayed on as a frontline health worker, working in the Polio Programme as a team member and eventually rising in the ranks to become an area in-charge.

As vaccinators, there was a time when Huma and Rukhsana were one team, a team that they were very proud of. “When important people came in big cars, we were the team that would be introduced to them because everyone knew we did our job well,” Rukhsana says. “Everyone who saw Huma was amazed at how much she could walk in a day and now…I would have never imagined that one day Huma won’t be able to walk.”

“Both of us still forget what happened. Last night, someone came knocking on the door with some tea and I couldn’t find my slippers, so I asked Huma where hers were, but then I remembered that they would be somewhere on the railway tracks that day,” she adds.

Much of Huma’s nights are spent in pain, especially in the feet that are no longer there. “I think it’s the nerves, my nerves still feel the pain. I can feel my toes hurting, and then realize that they aren’t there anymore.”

Despite a life-changing loss, this is the work Huma still wants to do. “I want to return to work in polio,” she says with a belief that better days are yet to come. The accident has offererd a new level of acceptance and grace. “If God has put me through this difficult time, then I will also be given the strength to bear it.”

“My father cries a lot about this. I told him we have to accept things as they are. This has happened, Allah has put us through a difficult time. If one door closes, another one opens.”

The Bonds That Strengthen

The accident has redefined the meaning of family for Huma. The outpouring of support from colleagues and leaders in the Polio Programme has been overwhelming. For Irshad Sodhar, Coordinator for Sindh’s Emergency Operations Centre, ensuring Huma’s recovery is a mission.

“Looking after the wellbeing of frontline workers is most important. While they do this arduous job selflessly, it is the programme’s duty to support them when they face any adverse situation, especially in the course of their work,” he says.

He is a frequent visitor to the family, and Huma and Rukhsana both look forward to seeing him.

“It is my mission to ensure that Huma gets back on her feet. After the accident, I mobilized everyone we could, from the National EOC Coordinator to the Sindh Health Minister and Deputy Commissioner. We have worked to ensure the family has enough funds and the house is made disability friendly with toilets remade and all parts of it accessible for her. I am amazed by her resilience. After all this, she still wants to work to end polio,” he says, adding “Global polio eradication depends on the motivation of frontline workers. We can’t finish the job without the utmost support of frontline teams on ground.”

When Dr Shahzad Baig, the National EOC Coordinator, talks about Huma, the word that is oft repeated is of family. “Huma is one of the most remarkable people I have ever met,” he says. “We met soon after the accident and I was amazed to see how unbroken her spirit was. She only had gratitude and determination to be better. This feeling of awe stayed with me for days after I met her,” he says.

“She is the true spirit of our polio family. We will make sure she recovers completely and is able to walk on prosthetic feet. Our polio partner, Rotary, has already provided the support for the prosthesis.”

For Dr Zainul Abedin, the WHO National Polio Team Lead, Huma’s unbreakable spirit exemplifies the strength within the polio family. “Huma’s journey, marked by both loss and unyielding hope, mirrors the dedication of health workers across the country. There are many brave souls like Huma who are part of this noble mission to end polio from Pakistan,” he said.

Dr Abedin added: “We salute Huma and every frontline worker, acknowledging their sacrifices and commitment, and will continue to ensure a highly supportive environment for them.”

Huma’s journey and resilience caught the nation’s attention on October 24, 2023, World Polio Day.

In a ceremony that highlighted the relentless efforts of health workers in the fight against polio, Prime Minister Anwaarul Haq Kakar honoured Huma with a shield appreciating her services. This recognition was not just for her contributions to public health but also for her unyielding spirit in the face of adversity. Huma was unable to travel to Islamabad. Dr Baig accepted the award on her behalf and the PM vowed to bring it to her himself.

As Huma prepares for a new chapter in her life, her story is not just one of loss and hardship, but of immense strength, community support, and unwavering hope. “Things have changed, but life goes on,” Huma says with a smile. “We have to embrace it, whatever it brings.”

Huma is eager to start working for polio eradication again.

Sindh EOC Coordinator Irshad Sodhar got frontline workers from across Pakistan to send her messages, all of them expressing their belief in her and wishing for her strength. Huma had a message for them too: “You are not alone. There is a huge programme behind you, which is there for your support. Your work is greater than you think.”

Rukhsana says she has never felt as supported since she started working in 1995. “In this time, I have really felt what it means to be part of a family.”

By Zehra Abid,

Communications Officer, WHO Pakistan (Video by NEOC)