When a 5.9-magnitude earthquake struck south-eastern Afghanistan in the early hours of 22 June 2022, WHO’s polio workers were among the first responders. As dawn broke in Khost and Paktika provinces, and the extent of the devastation became evident, they helped attend to the many injured.

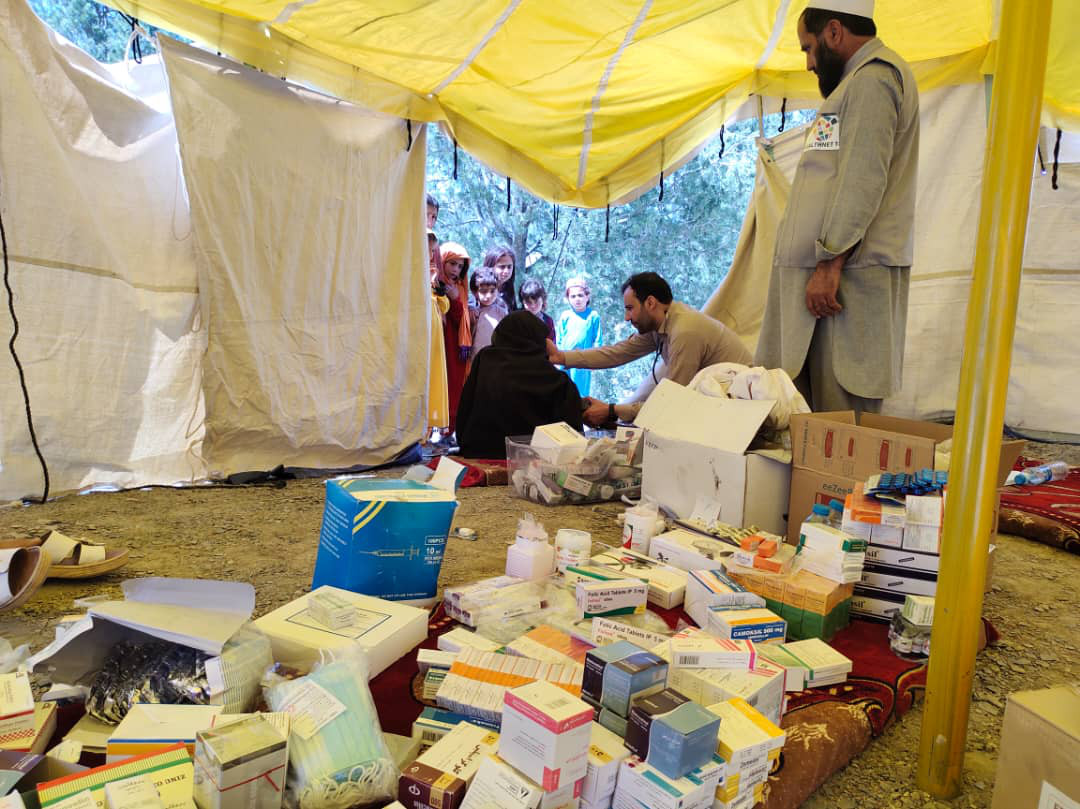

WHO’s polio teams dressed wounds, provided trauma care and generally gave a helping hand wherever needed. This included digging for survivors, putting up tents, unpacking trucks and distributing shipments of WHO emergency and surgical kits, medical supplies and equipment. Polio workers were also involved in the heartbreaking task of preparing the dead for burial.

Here they reflect on their experiences.

Mr Najibullah, District Polio Officer, Gyan district, Paktika

Mr Najibullah, District Polio Officer, Gyan district, Paktika

My name is Najibullah, and I am the District Polio Officer for Gyan district in Paktika province. When the earthquake struck Gyan, I was at home, sleeping. I woke up because the house was shaking and dust was falling on me. It was dark and I didn’t know what had happened until I heard people’s shouts.

“We used a tent and beds and chairs from people’s houses and by late morning we had built a small temporary clinic.”

The phones were still working so I called our Provincial Polio Officer and let him know what had happened. I was the first person to report the earthquake in Gyan. After finishing my call, I ran to help rescue the injured.

It was dark but I could see houses were destroyed and could hear people screaming and crying. We used any cars that were available to transport the injured to the nearest clinic for first aid. But there were many injured and the clinic was 4 kilometres away, so we established a makeshift clinic in the village. Our polio staff, who live all over the district, came to help. We used a tent and beds and chairs from people’s houses and by late morning we had built a small temporary clinic.

I have worked for the Polio Eradication Programme in Gyan for 20 years. Over the next 5 days, I used my local knowledge to help guide partners and other agencies, directing them to the most affected areas. I accompanied United Nations partners to every village – anywhere people needed assistance and medical services – and used my familiarity with the region to help map out the UN-wide response.

In Gyan district, we have 11 villages, and more than 19 000 people were affected by the earthquake. It was difficult to move from one village to another because the roads, which are unpaved, were badly damaged by the earthquake.

In such a devastating time of need, I did everything I could to help my people, both day and night. I remember I even helped rescue livestock trapped in the rubble.

Dr Gul Mohammad Marufkhil, Coordinator of the Polio Eradication Programme, Paktika

My name is Dr Gul Mohammad Marufkhil, and I am the coordinator of the polio programme in Paktika province. I was in Sharan district, about 80 kilometres from Gyan, when the earthquake struck.

“We did all we could to make sure we provided support and help to our communities.”

When Mr Najibullah called me to tell me what had happened in Gyan, I immediately called WHO’s field office in Gardez. It was the middle of the night, but I organized an emergency meeting with all our local partners to begin to respond to the earthquake. We requested medical kits, food and tents to be sent to the affected area as soon as possible.

I was tasked with communication, coordination, and arranging aid packages for communities affected by the earthquake. My job was to gather information about the number of injured, the casualties and the level of destruction to buildings and infrastructure and share this with our partners.

In the morning, equipment including medical kits, food packages and tents began to arrive from Gardez, Ghazni, Kabul and Khost. I worked with our teams to transport and distribute these items in both Bermel and Gyan districts.

I am very proud of all our work during that difficult time. We did all we could to make sure we provided support and help to our communities.

Dr Sultan Ahmad, Polio Provincial Officer, Paktika

My name is Dr Sultan Ahmad, and I serve as the Polio Provincial Officer in Paktika province. I was in Urgun, a neighbouring district to Gyan, when the earthquake struck. The shaking woke me up, but there was no destruction near me.

“I managed the flow of injured people to ensure that those who could be treated at Urgun were seen to there and the critically injured transported to Gardez or Kabul.”

After Mr Najibullah called and told me about what had happened in Gyan, I immediately went to the district hospital and alerted the doctors and other staff to prepare to receive the injured. I then dispatched a team of doctors and nurses and 7 ambulances to Gyan as well as to Bermel district, which had also been severely damaged.

As the sun rose, more ambulances and medical teams arrived in Urgun. I managed the flow of injured people to ensure that those who could be treated at Urgun were seen to there and the critically injured transported to Gardez or Kabul for further treatment. When medicines and medical kits began to arrive, I coordinated their distribution to the district clinics where the injured were being treated.

Many, many people were injured as a result of the earthquake, and I am very proud of my role in organizing teams and helping save lives.

Mr. Jan Mohammad, District Polio Officer, Bermel district, Paktika

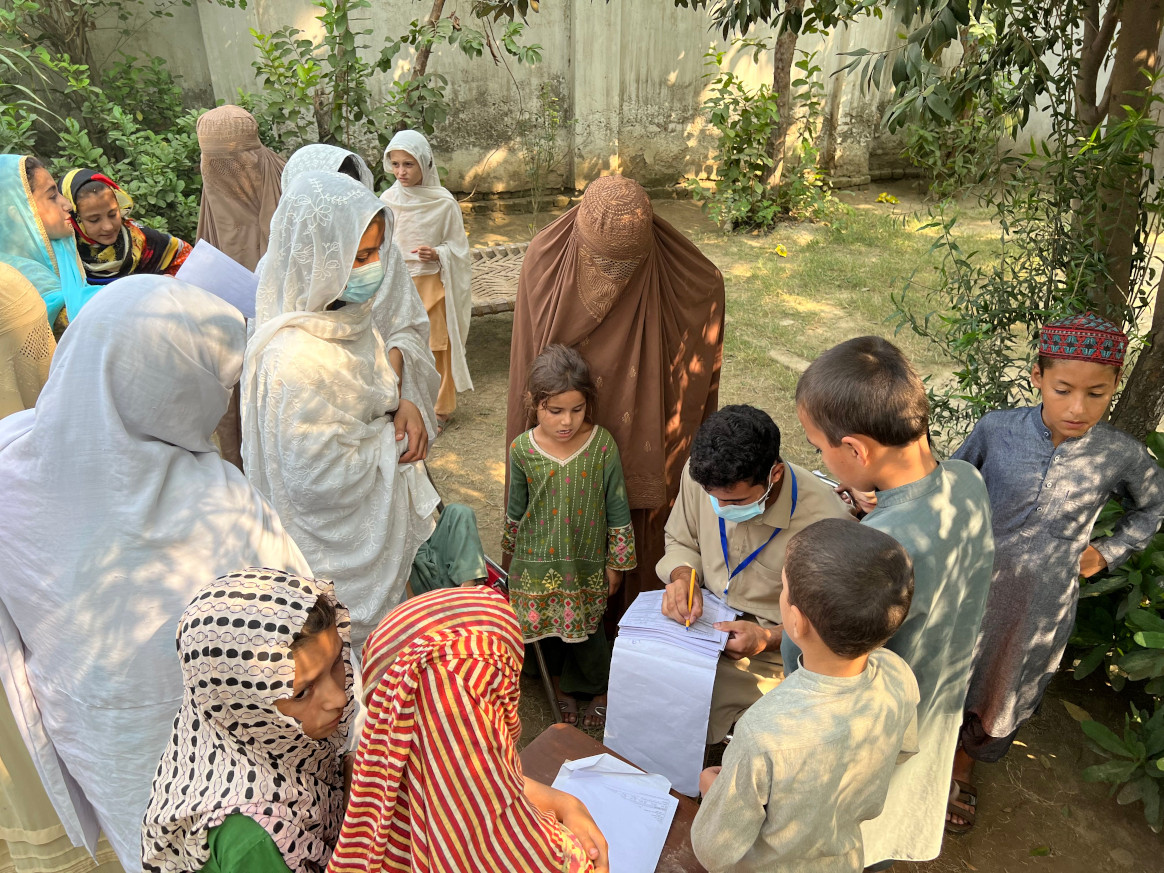

My name is Jan Mohammad, and I am the District Polio Officer in Bermel district in Paktika province. I was in Bermel when the earthquake happened. I felt the earthquake; it was very strong, so I knew people would be affected. I immediately mobilized our local polio workers to travel with me to the affected area and assist the survivors.

“About 9000 people live in the area but there are no clinics and no doctors, so we provided essential first aid to those in need.”

It took us about 5 hours to drive there. When we arrived, we saw buildings had collapsed and people were trapped. We jumped out of the car and began digging in the rubble to extract people trapped beneath their damaged houses. About 9000 people live in the area but there are no clinics and no doctors, so we provided essential first aid to those in need. As makeshift clinics were set up and mobile health teams arrived, our team facilitated the transportation of the injured to the clinics.

I worked with other UN agencies, using my local knowledge to help guide them to the location of communities where there might be more injured people. I also advised on where to set up temporary clinics and distribution points for food packages to reach as many people as possible.

I took great pride in everything my team did to help the people of my district at such a critical time.

Mr Najibullah, District Polio Officer, Gyan district, Paktika

Mr Najibullah, District Polio Officer, Gyan district, Paktika

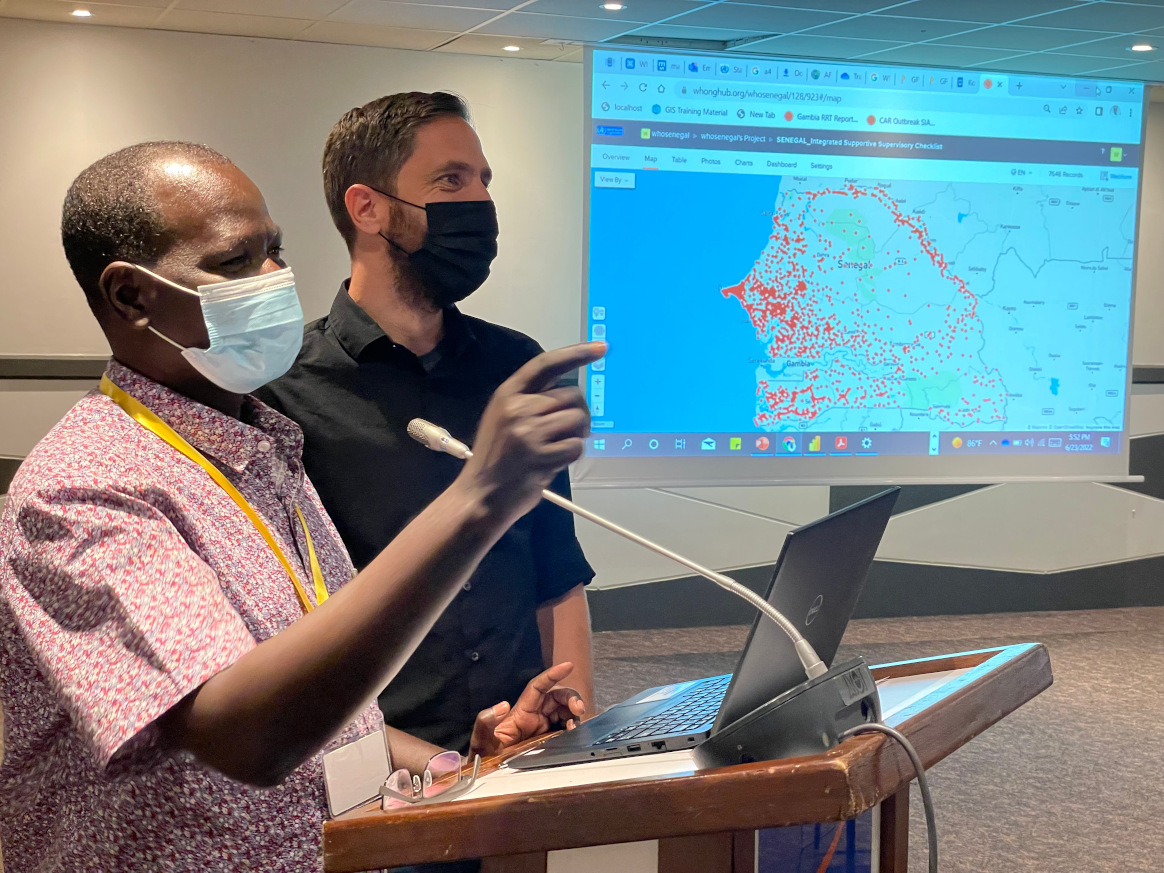

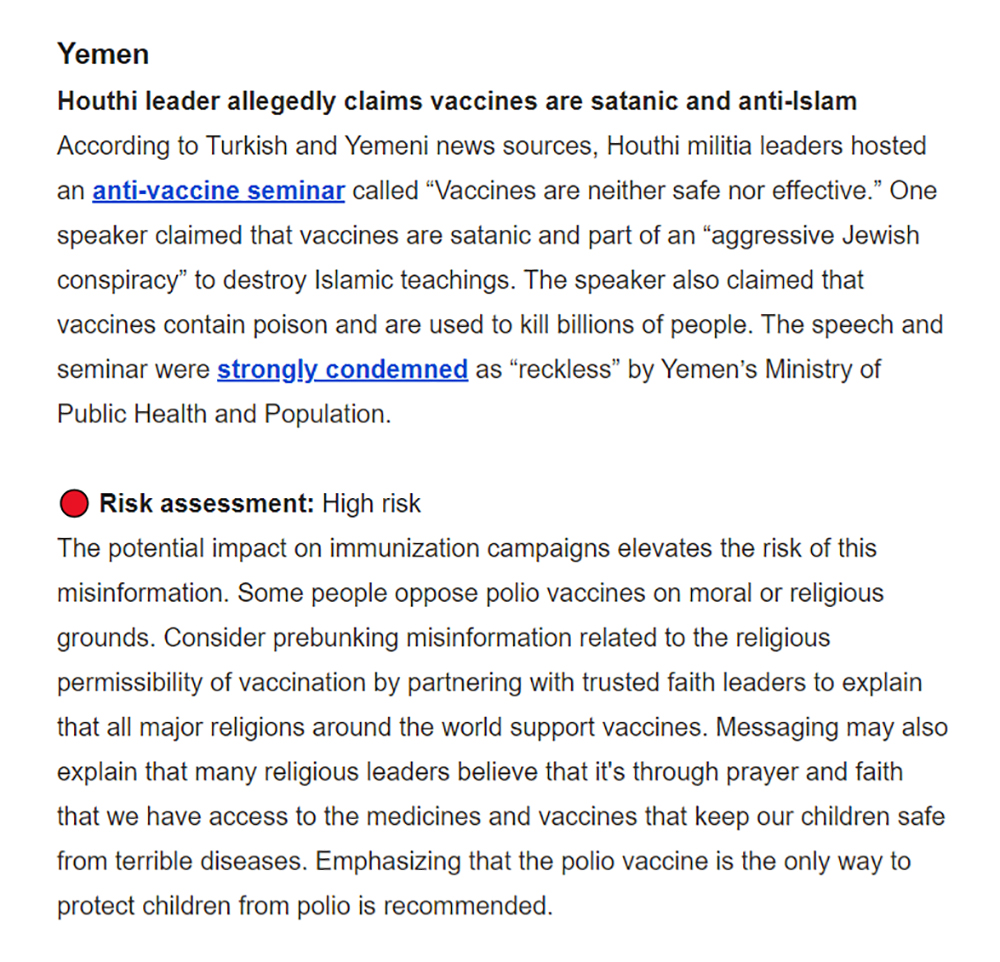

The DCE is made up of a central hub that tracks polio misinformation online, develops accurate messaging, and supports digital volunteers and UNICEF country offices. The hub is driven by a global team of experts spread across public health, social behaviour change, online social listening, advertising, content design and influencer marketing.

The DCE is made up of a central hub that tracks polio misinformation online, develops accurate messaging, and supports digital volunteers and UNICEF country offices. The hub is driven by a global team of experts spread across public health, social behaviour change, online social listening, advertising, content design and influencer marketing. Clear and accurate messages are crucial

Clear and accurate messages are crucial