Dr Arshad Quddus is the coordinator of the Polio Strategy Support and Coordination unit at the World Health Organization (WHO). In August, he took part in the meeting of the Expert Review Committee (ERC) in Nigeria. Here, he speaks about the extraordinary efforts in Nigeria to date, the work still to be done, and what motivates him to eradicate polio.

What was the purpose of the ERC meeting in Nigeria last week?

This ERC meeting in Nigeria reviewed the progress made in Nigeria and identified the ways and means to strengthen the gains of the last few years. Finally, the committee identified the major risks and advised the Nigeria team on how to address them.

Nigeria has recently passed a big unofficial ‘milestone’ with one year of no wild poliovirus cases confirmed. What factors are responsible for this progress?

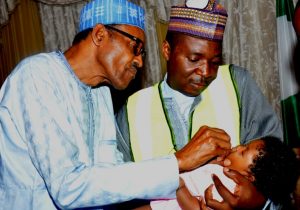

the last case was confirmed in Nigeria. High level political commitment has been crucial for progress so far. © Government of Nigeria

I think there has been remarkable progress with extraordinary efforts made to achieve it. There have been a number of innovations that the programme has incorporated that can be labelled as game changers. The most important of these was getting political commitment at all levels, with the engagement of the President, religious and traditional leaders, as well as the community networks. By improving accountability frameworks with clearly described roles and responsibilities, establishing health camps in some of the very difficult to reach areas, developing new strategies to vaccinate children, substantial progress was made.

How confident do you feel in the progress seen in Nigeria against wild poliovirus?

The ERC review has increased our level of confidence because it reviewed the situation very critically. It seems like Nigeria’s surveillance system has improved overall because it is showing better indicators, and because no case of WPV or positive environmental sample has been found in the last year. So there is a degree of confidence in this progress that has been made in Nigeria. Having said that, we know that pockets of low immunization coverage remain in some of the high-risk areas. That is why everyone needs to redouble their efforts to fill all the remaining gaps, both in vaccinations and in surveillance.

What are the risks to polio eradication in Nigeria now?

During the ERC everybody agreed that the important thing is to build on the gains, and to do that we need to be aware of the risks. There are expanding areas of insecurity and inaccessibility, particularly in Borno and Yobe in the north east. There are still pockets with low immunization coverage in Kano, Kaduna, Sokoto and Katsina. The programme really has to focus on these areas to improve population immunity and to fill residual surveillance gaps. There is a third big risk that the sense of achievement could lead to complacency that the job is done. There is still a long way to go. Polio needs to be kept top of the priority list until the job is done.

What does the programme have to do to target those areas of insecurity in the north east?

The programme has rich experience in reaching children in insecure and inaccessible areas. For example, permanent transit teams vaccinate any children going in or out of those areas; there are campaigns that seize on windows of opportunity as and when areas open up. We are also scaling up surveillance and immunization activities in camps for the internally displaced populations and enhancing coordination with countries where the population of these conflict-affected areas have moved, such as Cameroon and Niger. In addition we are expanding environmental surveillance, including to key urban areas in Borno.

What are the three key things Nigeria has to do to ensure it becomes polio-free?

Nigeria has to maintain the highest possible level of protection through immunization coverage, and figure out how to reach the children we are currently missing. This is the time for Nigeria to be very vigilant and alert and to redouble its efforts, which means they have to make sure that the surveillance system is strong and gaps are filled. And thirdly, we have to continue to have the highest level of political commitment and to enforce accountability.

Do you think we are close to overcoming the remaining challenges?

I think this recent progress in Nigeria paves the way for Africa to become polio free. It is challenging, but the recent progress that is being made is encouraging. Certainly Nigeria, and Africa, is closer than ever. But even if Africa finishes the job, a lot will depend on how quickly we progress in Pakistan and Afghanistan. We know from past experience how quickly and how far poliovirus can spread. But we are very, very close. We are at the brink of achieving eradication.

What motivated you to work in polio eradication?

I joined this programme in 1999. In those early days, the sense that eradication was achievable if we just improved immunization pulled me in. I spent ten years working in Afghanistan. Vaccinating children in those conflict-affected and difficult to access areas was very challenging. We would work to find additional children to immunize, protecting them not only from polio but also from other vaccine preventable diseases. There was always a sense of achievement and satisfaction in trying to overcome these challenges.