“Ali was a humble, simple person. He had talent – real talent – in communicating the importance of vaccines to people in his community and around Somalia. He was seen by many as a hero.”

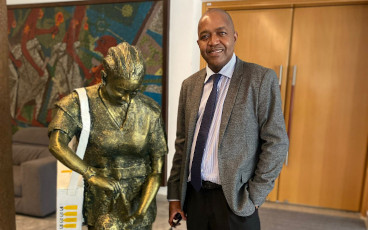

This is how Mahamud Shire, a long-time collaborator of the World Health Organization in Somalia, remembers the late Ali Maow Maalin.

Ali was the last person in the world to be infected with naturally occurring smallpox. After contracting the virus, he decided to devote his life to improving health through vaccination. He did so until his sudden passing in his home district of Merka on 22 July 2013. At the time, he was still serving with WHO as a district polio officer as part of the global polio eradication programme. He was 59 years old.

2018 marks five years since Ali’s passing. This article is being published to commemorate his life and achievements.

Smallpox

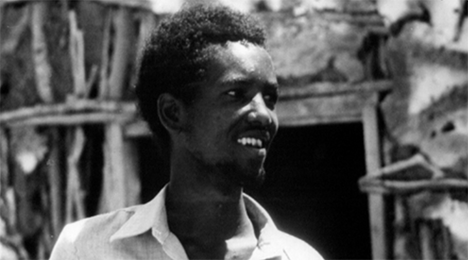

Ali Maow Maalin was born in 1954 and worked as a hospital cook. Aged 23, he contracted the smallpox virus.

Although he had previously worked as a vaccinator in the smallpox eradication programme, he himself had not been vaccinated. Fearing the needle, he had avoided the shot by holding his arm when vaccinators came to visit, pretending he had already been inoculated.

“I was scared of being vaccinated then. It looked like the shot hurt,” Ali would later recall when asked why he wasn’t immune on the day the smallpox virus caught up with him.

A man carrying two smallpox-infected children from a nomad encampment had been driving all day, looking for the local isolation camp. Taking wrong turn after another, he finally decided to stop and ask for directions. He did so at the hospital where Ali worked.

“Ali didn’t think about it twice – he jumped in the van and immediately offered to accompany the driver,”

Mahamud tells us. The driver then asked Ali if he had been vaccinated, but Ali simply said: “Don’t worry about that. Let’s go.”

It only took 15 minutes for Ali to contract the virus. Luckily, the form he caught was the less virulent one – variola minor – although still potentially lethal.

Nine days later, Ali started feeling sick.

Making history

Ali’s infection did not lead to a new outbreak. This was primarily because once the hospital where he worked found out he was sick, he was told to stay home. In the meantime, the hospital stopped accepting patients while everyone inside was being vaccinated and quarantined.

A 2011 WHO publication reports how a special team set out to vaccinate everyone in the 50 houses around Maalin’s home. Over the course of two weeks, a total of 54 777 people were vaccinated.

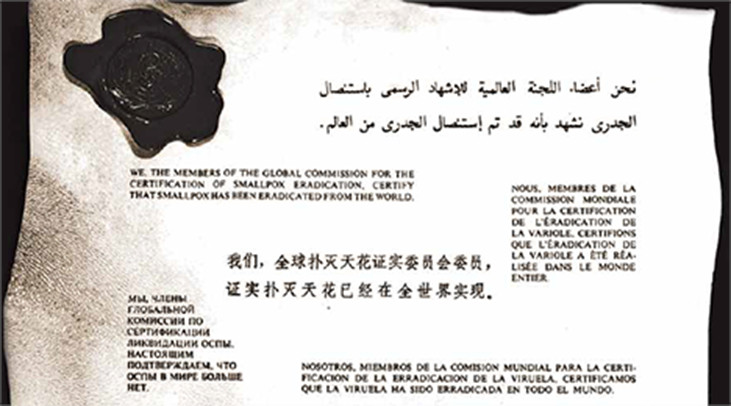

Effectively isolated, the virus didn’t spread. Smallpox was officially declared eradicated in 1979.

This was the first time in history that a major disease had been completely destroyed by human endeavour.

After sickness – a lifelong commitment to polio eradication

After recovering, Ali decided to commit his life to the eradication of another major disease: polio.

Beginning his new role as a vaccinator, he was determined that his own encounter with smallpox would serve as a powerful reminder of why immunization is so important.

“When I meet parents who refuse to give their children the polio vaccine, I tell them my story,” said Ali in 2006. “I tell them how important these [polio] vaccines are. I tell them not to do something foolish like me.”

When we spoke with Mahamud Shire, Ali’s friend and collaborator, we got the unequivocal impression that everyone who crossed paths with Ali, in one way or another, simply liked him.

“He was this really happy person – happy that he was the last case of smallpox still alive, happy that he now had the chance to do his part for his community,” Mahamud says.

Mahamud, who first met Ali in 1977, says Ali’s methods were very successful.

“The way he communicated the importance of vaccination to people – his entire approach – was very effective,” Mahamud says. “He would tell people, ‘I’m vaccinated, and I’ll never get sick’.”

Getting the job done

His work, together with that of his WHO colleagues and peers, helped crush Somalia’s polio outbreak in 2005, protecting children from the paralyzing virus.

When Ali suddenly passed away in July 2013, he was still working with WHO through the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, trying to fulfill his quest.

We have never been so close to the final eradication of polio as we are today. When smallpox was eradicated, there were a total of about 52 000 cases each year of wild polio virus. In 2017, only 22 cases of wild poliovirus were reported worldwide.

Now, as with smallpox, the final steps are the most challenging. To eradicate the virus, we must reach every last child with vaccines. We must maintain political and civil society commitment, continue filling immunization gaps, and strengthen disease surveillance in difficult settings.

Ali’s work in communities across Somalia is a reflection of WHO and partner’s long-standing commitment to increasing access to vaccines – everywhere.

One of Ali’s most famous quotes, the one most often used to capture his energy, enthusiasm and firm commitment, is one that puts smallpox and polio one next to the other.

“Somalia was the last country with smallpox. I wanted to help ensure that we would not be the last place with polio too.”