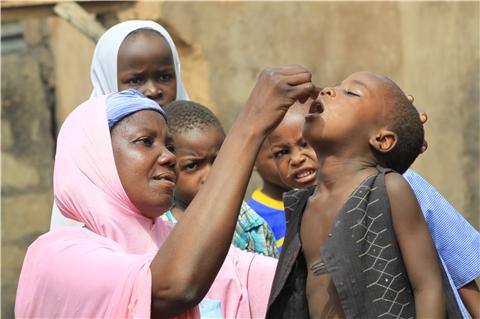

16 August, 2012 – To stamp out polio in Nigeria, every child must be identified, reached and vaccinated – each and every vaccination round. Every unvaccinated child increases the risk of polio spreading rampantly once more, threatening not only the rest of the country, but the entire importation belt of west and central Africa.

This is why it is worrying that the neighbouring states of Zamfara and Sokoto have had 12 cases of polio this year, compared to only three at this point in 2011. Among the various reasons for this increase in cases, operational difficulties stand out. These are challenges in planning and implementing vaccination rounds, which are preventing children from receiving the polio vaccine.

Reaching huge swathes of people across the large and difficult terrain of Zamfara and Sokoto is far from easy, particularly in round after round of campaigns. Microplans laying out the strategy to reach every last child certainly help, but, to be as effective as possible, they must be repeatedly updated – particularly to take into account the current whereabouts of any of the ten million nomads who circulate through northern Nigeria. Even with these plans in place, reaching every child in the most remote villages can be a daunting task, especially in areas that are inaccessible by road. Vaccination teams and their supervisors must be motivated to travel over difficult terrain time and time again.

But sometimes the reason why children miss out is much simpler – they just aren’t at home when the vaccinator calls. Unlike in many countries, children in states such as Zamfara and Sokoto are not always found with their mother or father. Instead, children as young as three can be sent out to herd cattle on their own or are looked after at the playground by brothers or sisters, who are, themselves, sometimes as young as five years of age. In Sokoto, for example, 32% of children who were absent from the house in the September 2011 vaccination campaign were at the playground, 27% were in the fields, and 19% were attending a social event with their mother or father.

The programme is tackling these operational difficulties with fresh ideas. Microplanning strategies have been refined, using lessons learned from India’s successful eradication programme. Mapping and oversight have been improved by the introduction of GPS and mobile technology. The ‘Nomad Project’ is producing plans to reach nomadic populations with both the vaccine and tailored communications. And vaccinators who consistently reach a high percentage of children will be recognised and rewarded, hopefully inspiring those on the ground to keep trying their hardest.

Importantly, hardworking polio personnel are also having their loads lightened by a 300% increase in human resources. In the last two months, 2,000 new staff have been trained, expanding the programme’s overall capabilities.

These changes are intended to re-energize, improve and refresh the programme, so that the last remaining children will receive their drops of polio vaccine too.