While the partners of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) know a great deal about how to stop the poliovirus, they are always seeking out ways to improve and bring us closer towards eradication. Currently, clinical trials are helping the GPEI to solve some of the biggest challenges standing in the way of a polio-free world, such as inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) shortage, how to deliver fractional dose IPV and how to respond to polio outbreaks in the most efficient way possible and accelerate eradication.

By investing in cutting edge research, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) and the World Health Organization (WHO) together with their partners around the world are using clinical trials to find answers to questions that will make all the difference in achieving all objectives of the Polio Endgame Plan.

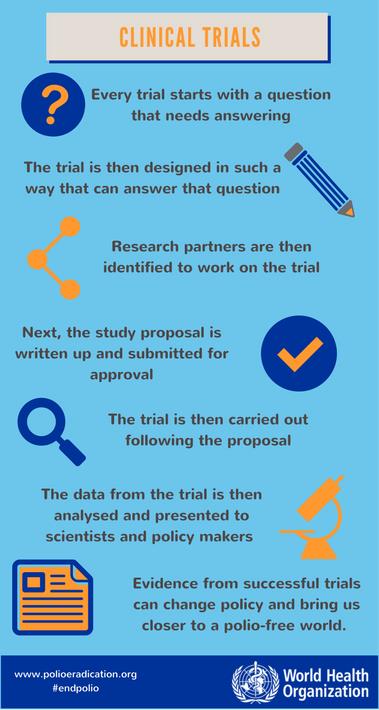

Clinical trials

Clinical trials are deemed the ‘golden standard’ of research methods. By comparing outcomes in two or more groups, evidence is gathered on how well different methods work. Because the study design can make sure the groups are identical to each other in all other ways through ‘randomization’ of the study participants, carefully done clinical trials lead to a measure of certainty about the validity of the outcomes that some other study designs cannot achieve.

Clinical trials are deemed the ‘golden standard’ of research methods. By comparing outcomes in two or more groups, evidence is gathered on how well different methods work. Because the study design can make sure the groups are identical to each other in all other ways through ‘randomization’ of the study participants, carefully done clinical trials lead to a measure of certainty about the validity of the outcomes that some other study designs cannot achieve.

Strengthening Outbreak Response

Responding to outbreaks of polio has always been one of the core activities of the GPEI. Now, with polio in fewer locations than ever before, it is more essential than ever that any outbreak is stopped as quickly as possible. Yet gaining access to children to give them the vaccines they desperately need can be a challenge, with the most vulnerable living in insecure or conflict affected areas.

Clinical trials are revolutionising our approach to stopping polio outbreaks in these challenging locations. A trial published in 2015 by scientists from WHO and Aga Khan University in Pakistan looked at whether doses of the oral polio vaccine (OPV) could be given closer together and still generate the same level of immunity in vulnerable children.

The workings of a clinical trial in practice

Doses of OPV are usually given with four week intervals. However, in security compromised areas, or when an outbreak requires a rapid increase of immunity to stop the virus spreading, being able to give the doses closer together and generate immunity faster would be a useful tool for outbreak response, enabling children to be vaccinated in shorter periods of access.

This clinical trial sought to answer the question of whether monovalent OPV type 1 (mOPV1) given at shorter time intervals would generate the same levels of immunogenicity as it does when given at four week intervals. The trial was designed to be done in multiple centres, with all participants randomised to avoid selection bias, and with four trial groups to compare different outcomes. It was carried out at five primary healthcare centres in low-income communities in and around Karachi in Pakistan.

Newborn babies who met the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned into one of the four groups and then given one of four different patterns of doses when they reached six weeks of age: mOPV1 with an interval of one week, of two weeks, of four weeks; or two doses of bivalent OPV four weeks apart.

The study found no significant difference in the levels of immunity between the group given the normal dose schedule, and those with shorter interval doses. This led the authors of the paper to conclude that a seven day interval between doses could be used, especially when temporary opportunities for safe access in areas of conflict can be granted.

From research to practice

Thanks to clinical trials such as this, polio eradicators on the ground are honing their skills. Following confirmation of cases in polio in Nigeria in August 2016 after two years with no detected cases, four rounds of short-interval additional dose campaigns were carried out to rapidly increase immunity as part of the regional emergency outbreak response. Many vaccination campaigns now operate to this schedule, especially when focussing on high-risk areas.

Clinical trials are helping to answer more questions that will take us over the finishing line to end polio. Recent research has showed the best dose schedule of mOPV2 to build up immunity against type 2 polioviruses, assessed mucosal immunity after fractional dose inactivated polio vaccine, and more. It is this technical attention to detail and innovation that has made the GPEI one of the most successful public health programmes of the age, and it is what will end polio, once and for all.

| The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) is highlighting the innovations that are helping to bring us closer to a polio-free world. Find out about other new approaches driving the polio eradication efforts by reading more in the Innovation Series. |