Dr Fiona Braka holds one of the highest-stake roles in the African regional polio programme – supporting the Government of Nigeria in their fight to defeat wild poliovirus.

She is the first woman to hold her position in Nigeria, and before that was the first female polio team lead in Ethiopia.

Fighting the last wild virus in Africa

Dr Braka’s work involves leading the country team to strengthen routine immunization and maintain high quality disease surveillance systems in Nigeria. She is also heavily involved in the COVID-19 response, lending expertise established over decades of fighting polio.

In 2016, the detection of wild virus in Nigeria after nearly two years without cases was a devastating setback. “When the outbreak broke out, I was in Uganda on a break with my family. I was having lunch with a friend and my phone was ringing, persistently ringing – a Geneva number. When I picked up the phone it never crossed my mind it would be a wild virus,” Dr Braka remembers.

“A good proportion of Borno state was inaccessible due to armed conflict. Delivering vaccination services and conducting surveillance in that area had not been easy. With interventions going on to address the conflict by the Nigerian Government, some ground was gained, and people trapped for over three years were able to move out of the liberated areas to internally displaced persons camps. With population movement, a wild polio case was detected in an internally displaced child.”

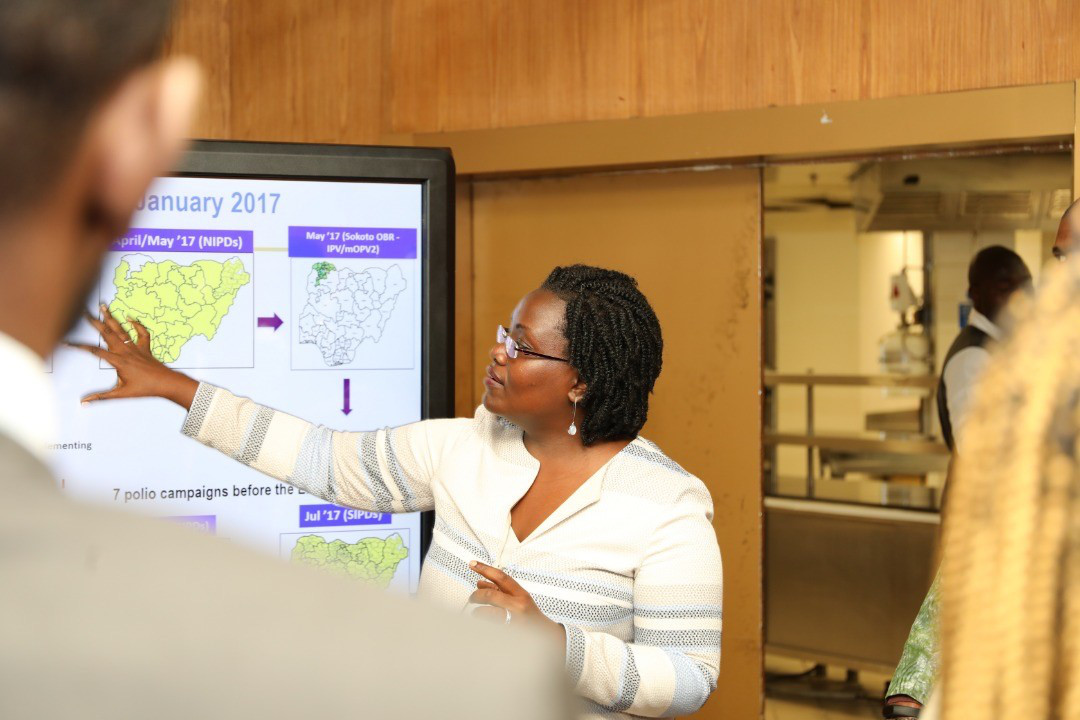

Cutting short her family holiday, Dr Braka raced to Borno to help launch a truly innovative outbreak response with the government and partners. Adapting strategies for polio response to an insecure setting, the programme started settlement-based microplanning guided by local security assessments, innovative surveillance approaches, and the use of GIS and satellite imagery to estimate trapped populations.

The estimated number of children inaccessible to vaccinators has dropped from over 400,000 in September 2016 to less than 30,000 in May 2020 – an enormous achievement for the programme.

Balancing motherhood and a career in public health

The challenges were very different when Dr Braka was working on the 2013 Horn of Africa outbreak in Ethiopia’s Somali region. Cases of polio were occurring among pastoral communities and the programme had to rethink tactics to ensure the children of nomadic populations could be reached with vaccines. To maintain the cold chain, polio teams travelled on donkeys or on foot through the bushes. Community leaders among the nomads were employed to help vaccination teams reach families on the move.

“I recall the advice of a parent of a nomadic child who had contracted polio. He said, “We follow where the clouds and rain go – unless the polio programme also moves with the clouds and the rains as we do, you will never reach us and our children will never get the vaccine”. This became a guiding quote for us,” Dr Braka remembers.

This was also a time of personal challenge, as Dr Braka’s youngest daughter was less than a year old. On one occasion, Dr Braka brought her baby with her to a vital cross-border collaboration meeting in Somali region between the Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia teams. She recalls, “I had to stay in the same hotel as the meeting so I could run upstairs during the break to breastfeed. That moment really stands out an example of the tough decisions you must make as a parent.”

Dr Braka praises steps taken so far to promote women’s professional development in public health and leadership, whilst noting there is more to do.

“The WHO Regional Director for Africa, Dr Matshidiso Moeti, has provided opportunities for capacity building for women. There has been the first training this year for senior women leaders in the African region – I am proud to be part of this.”

Part of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative Gender Strategy 2019-23 commits to promoting a gender-responsive organizational culture. By placing gender at the heart of operations, the strategy closely aligns with the policies of major donors to polio eradication including Canada, Germany, Australia and the United Kingdom.

Explaining why she is a strong supporter of gender equality at all levels of public health, Dr Braka finds, “Even occupying leadership roles you have to have gender in mind – you have to be prepared to prove yourself a bit more.”

“It remains our responsibility to create a policy environment that gives opportunities for men and women.”

A duty to end polio

Dr Braka emphasizes that many people forget how damaging the disease is.

“Whilst we have polio anywhere in the world, we are all at risk of cross-border virus spread. Until polio is eradiated globally, we must be on our toes with robust surveillance systems and infrastructure to deliver vaccines.”

Dr Braka has been able to sustain her demanding job in part thanks to the support of her family. She explains, “I have a very supportive spouse…He knows the polio programme as well as I do!”

“My late father was also very supportive of my career. My mother has been more than a mother – a strong pillar of support, mothering her grandchildren when I am not there and providing moral support in the background.”

She explains that she can’t imagine a next generation suffering from polio when a vaccine is available.

“Vaccines are a powerful tool and the evidence is clear for saving lives. They reduce burden on families, economically, emotionally, and they prevent the suffering of children.”

“We have a duty to secure children’s future to be healthy citizens.”