Acknowledging that our common goal is to attain ‘Health for All by All’, which is a call for solidarity and action among all stakeholders;

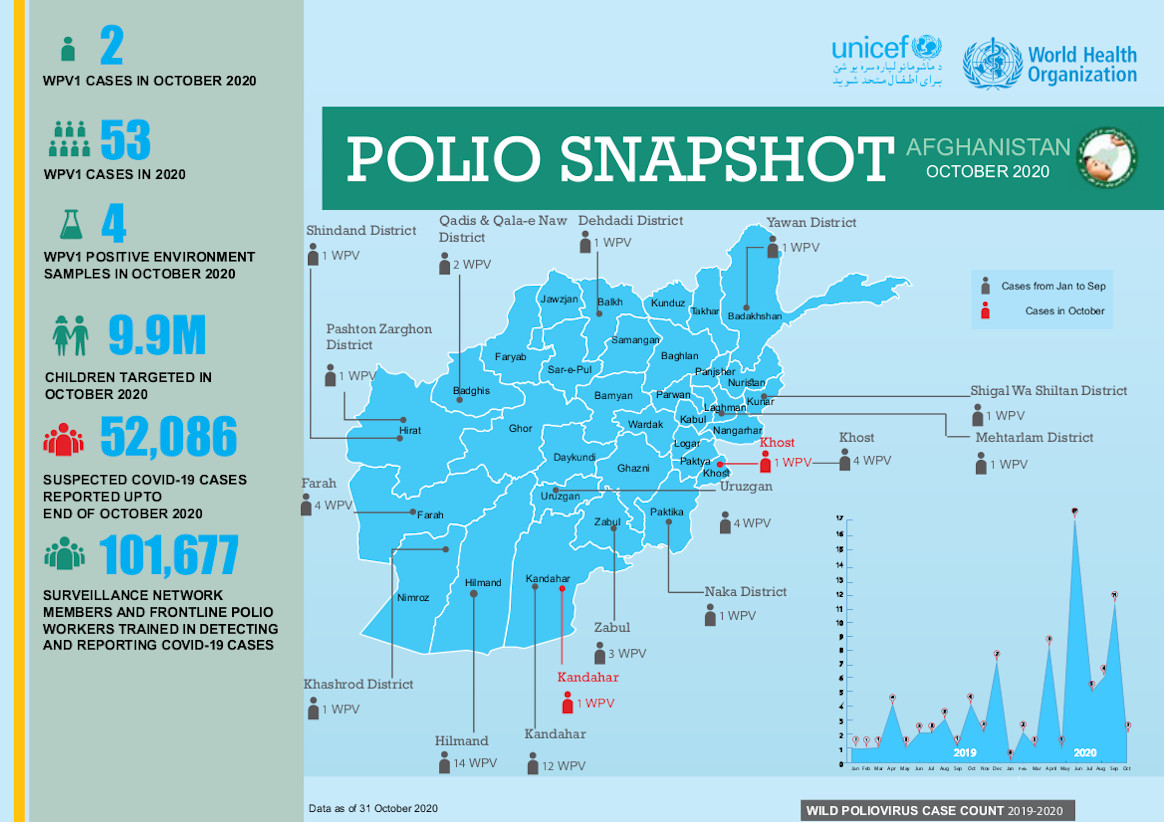

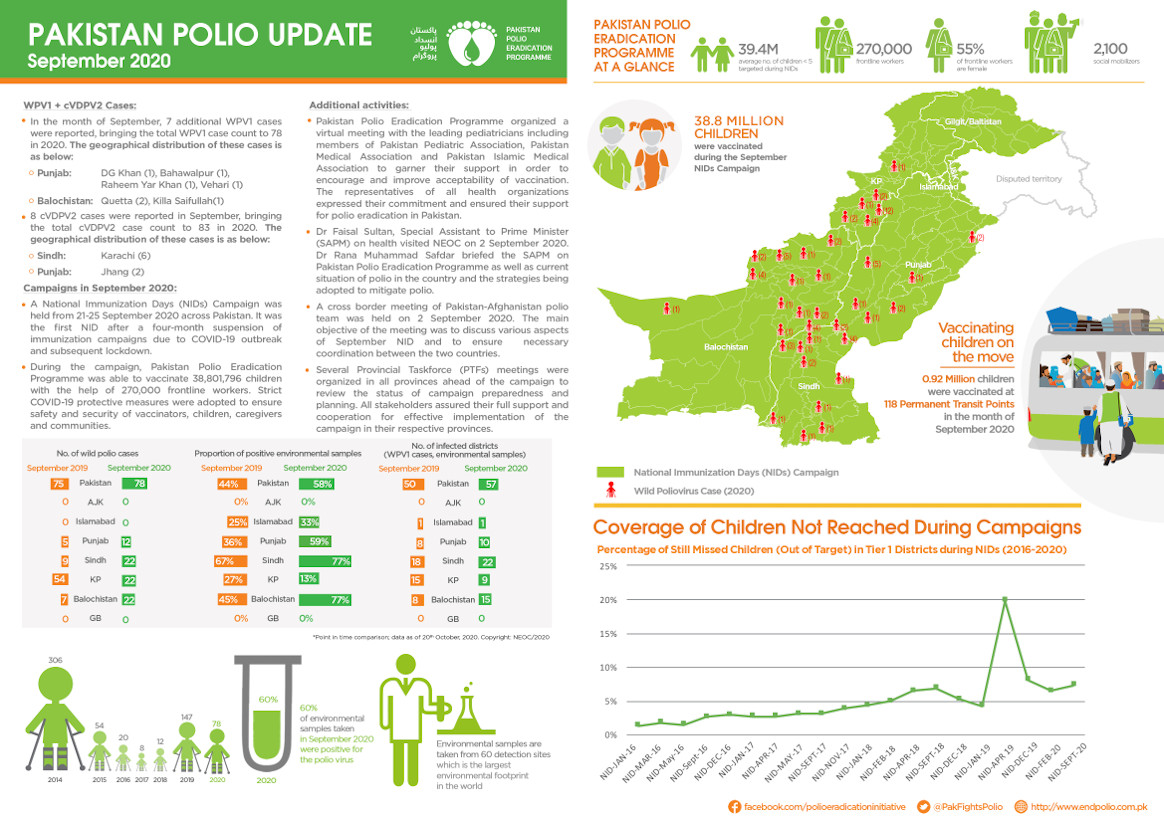

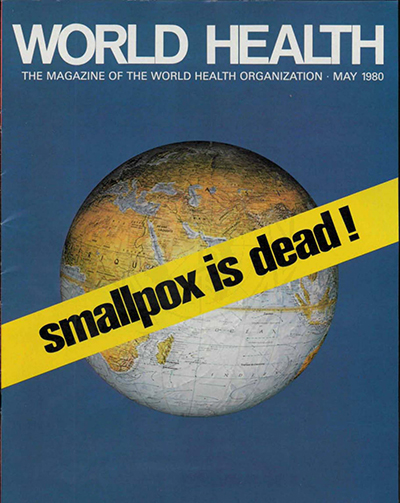

Noting the progress achieved globally in eradicating poliovirus transmission since 1988;

Noting with deep concern the challenges involved in stopping ongoing outbreaks of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) in the Region, without full access to vaccinate all vulnerable children in the affected populations;

Observing with alarm the prolonged outbreak in Yemen and the persistent restrictions on implementing outbreak response vaccination in the country’s northern governorates, and further observing that the cVDPV2 outbreak which has been continuing since 2017 is the world’s longest ongoing such outbreak;

Recognizing the Global Polio Eradication Initiative’s efforts to target its resources in the most impactful way by identifying particular areas affected by polio, including Yemen’s northern governorates and south-central Somalia, as “consequential geographies” – two of seven subnational geographies globally which together accounted for 90% of all polio cases in 2022 and which are all affected by broader humanitarian emergencies;

Recognizing the high risk of expansion of the polio outbreaks within and from the two Regional consequential geographies due to their complex emergency settings, limited access to high-risk populations, weak immunization services, gaps in coverage of supplementary vaccination campaigns, and unmitigated spread of misinformation and disinformation in northern governorates of Yemen;

Recalling that the international spread of polio is a Public Health Emergency of International Concern under the International Health Regulations (2005);

Observing with alarm that 197 children have been paralyzed by cVDPV2 in Yemen’s northern governorates, representing almost one-third of all global cases of this strain in 2022, and that the international spread of poliovirus from Yemen to Djibouti, Egypt and Somalia has been confirmed;

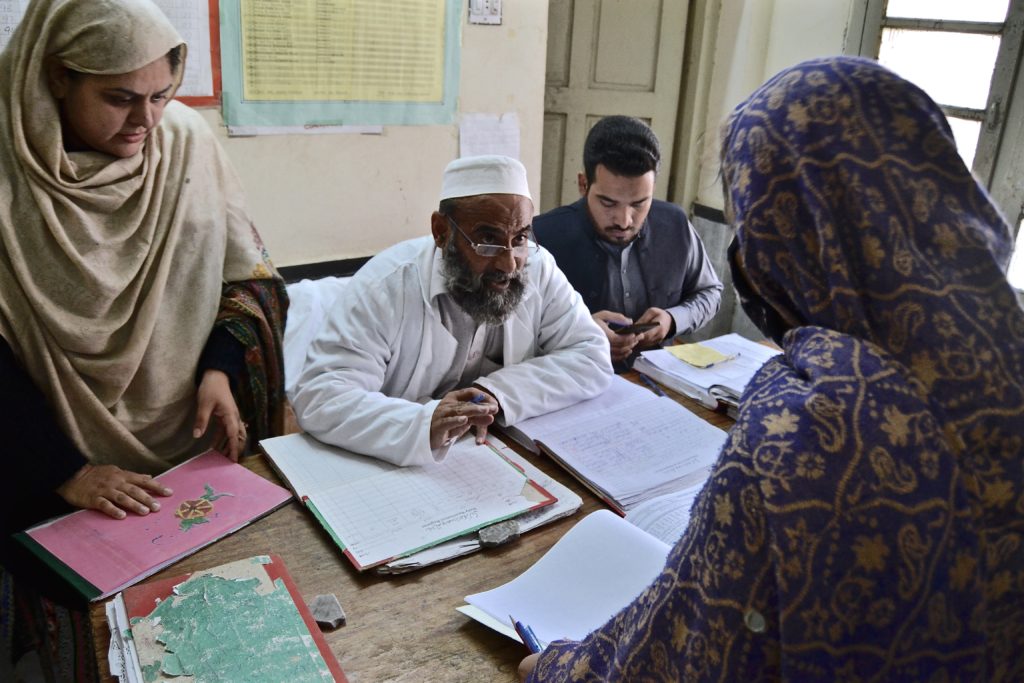

Recognizing the best operational approach and experience to vaccinate all children, especially infants and young children, against polio, and achieve more than 90% coverage to stop an outbreak is through house-to-house delivery of vaccination; and if that is not possible, to implement an intensified fixed site vaccination with effective mobilization of families and young children to fixed sites near their homes;

Recognizing the continued threat to all children posed by vaccine-derived poliovirus and the importance of regional solidarity and support to deliver on the goals of the 2022-2026 Polio Eradication Strategy, which have been endorsed and supported by a wide range of committed donors, such as Rotary International and Member States of the Region, in particular the UAE through the sustained commitment of His Highness Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, President of the UAE;

We, the Member States of the Regional Subcommittee on Polio Eradication and Outbreaks for the Eastern Mediterranean:

DECLARE THAT:

- The ongoing circulation of any strain of poliovirus in the Region is a Regional Public Health Emergency;

COMMIT TO:

- Mobilizing all needed engagement and support by all political, community and civil society leaders and sectors at all levels to successfully end polio as a Regional Public Health Emergency;

- Advocating with relevant community and subnational leaders to increase access and ensure full implementation of polio outbreak response in the most programmatically and epidemiologically impactful operational manner, ideally through house-to-house vaccination campaigns in all areas;

- Focusing efforts on reaching remaining zero-dose children in the consequential geographies of the northern governorates of Yemen and south-central Somalia, working in the broader humanitarian emergency response context;

- Helping to mobilize needed resources and highest-level international commitment to finalize and fully implement the Somalia Polio Eradication Action Plan 2023, in the context of competing health response priorities such as ongoing drought and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic;

- Helping to mobilize resources for the Global Polio Eradication Initiative partners to support the outbreak response in Yemen; and

- Helping to strengthen coordination with other public health and humanitarian efforts in Somalia and Yemen, to ensure closer integration in particular with routine immunization and the delivery of essential health and nutrition services to children;

REQUEST THAT:

- The international humanitarian and development communities scale up their support for providing essential services, including a robust vaccination response to the polio outbreaks in Somalia and Yemen using modalities that will deliver an acceptable level of coverage;

- The authorities and polio eradication partners in Somalia accelerate high-quality and rigorous implementation of the Somalia Polio Eradication Action Plan 2023 to stop the longest-running outbreak in the country and prevent the further spread of cVDPV2 by the end of 2023;

10. The national authorities and the Regional Polio Eradication programme strengthen cross-border coordination across Somalia, Kenya, Ethiopia, Yemen and Djibouti, considering the documented importation of cVDPV2 from Somalia into Kenya and Ethiopia, and from Yemen into Djibouti, Egypt and Somalia, and the high risk of further instances of cVDPV2 crossing international borders;

11. Authorities in northern governorates of Yemen, all immunization partners and the humanitarian development community respond urgently to the unmitigated vaccine-related misinformation and disinformation that is being disseminated, which is risking the lives of thousands of children in Yemen and across the Region;

12. All authorities in northern governorates in Yemen facilitate the resumption of house-to-house vaccination campaigns in all areas to ensure the delivery of vaccines to the youngest and most vulnerable children, and in areas where house-to-house vaccination is not feasible, make all efforts to implement intensified fixed-site vaccination through a modality that also includes robust social mobilization and outreach to ensure high coverage; and

13. The Regional Director continue his strong leadership and efforts to support the cessation of polio outbreaks in Somalia and Yemen, including by advocating for all necessary financial and technical support, reviewing progress, implementing corrective actions as necessary, and regularly informing Member States of the aforementioned and of any eventual further action required, through the World Health Organization’s Executive Board, the World Health Assembly and the Regional Committee for the Eastern Mediterranean.