From 21 to 23 April 2025, Afghanistan carried out its first nationwide polio vaccination campaign of the year, immunizing over 11 million children under five. The effort was synchronized with a similar campaign in neighbouring Pakistan—a vital strategy in what remains a race against time to stop poliovirus transmission in the last two endemic countries on earth.

Just four weeks later, Afghanistan implemented a second nationwide campaign in May, again synchronized with Pakistan. This back-to-back coordination is helping to close immunity gaps and intensify the fight against the virus ahead of the high transmission season.

Afghanistan and Pakistan form one epidemiological bloc, with interconnected polio transmission patterns and cross-border population movement meaning progress in one country is deeply linked to the other. Following a resurgence of wild poliovirus in 2024—paralyzing 99 children across both countries and expanding into both historic reservoirs and major urban centres—urgent, synchronized action has become more critical than ever.

The April and May campaigns in Afghanistan offered crucial opportunities to bolster immunity and prevent further spread of the virus. They followed earlier subnational campaigns in January and February, which focused on high-risk areas in the East, Southeast, and South Regions.

Despite a difficult operating environment, the Afghanistan polio eradication programme continues to adapt and innovate to protect every child. Since late 2024, the campaign modality in Afghanistan has shifted from house-to-house vaccination to a site-to-site approach, in which caregivers bring their children to designated vaccination sites to receive polio drops. While this change has introduced new challenges—particularly in ensuring high coverage in hard-to-reach communities—the programme is actively working to strengthen this approach as part of a broader “Strategic Reset.”

“The shift in modality requires new ways of working,” said Dr Mandeep Rathee, Polio Team Lead with WHO Afghanistan. “We are investing in strategies to ensure site-to-site campaigns are well-optimized and effective in reaching children who might otherwise be missed.”

East Region shows what’s possible

The East Region has emerged as a model of success. All districts in the region passed independent post-campaign monitoring using the Lot Quality Assurance Sampling (LQAS) method, indicating strong coverage and campaign quality. Revised microplans ensured that vaccination sites were placed closer to households—averaging fewer than four houses per site in line with Technical Advisory Group (TAG) recommendations.

This success has been underpinned by intensive community engagement, including the involvement of elders, religious leaders, and even children. Updated tools like child registration books and missed-child tracking formats have strengthened follow-up and accountability.

While these results demonstrate that site-to-site delivery can be effective when well planned and community-driven, global experience continues to show that house-to-house vaccination remains the most efficient strategy for achieving the highest levels of coverage—particularly in complex and high-risk settings. In the current context, the programme is focused on optimizing the tools and strategies available to reach every last child.

The success in the East is now informing similar efforts in other high-risk provinces, including the Central Region, where Farhad, a vaccinator based in Kabul, reflects on the importance of community engagement:

“On campaign day, I actively engage with community influencers including religious leaders, and encourage families to bring their eligible children to the site,” he said. “Community engagement and social mobilization are critical in the site-to-site modality.”

Parents like Jamal, who brought his four-year-old son to the site, echoed this appreciation: “Polio has no cure. Only the vaccine can protect our children. I’m grateful to the vaccinators who are here, even in difficult conditions, to make sure our children stay healthy.”

Strengthening routine immunization

In parallel, the programme is supporting efforts to strengthen routine immunization, particularly in areas where children may not be reached through all immunization efforts. In provinces such as Kandahar and Lashkargah, polio staff are helping to monitor routine Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) services, including at fixed and outreach sites—showcasing how polio infrastructure can support broader health system strengthening.

Reaching families through new approaches

During the April campaign, a new strategy to engage provincial and district governors, alongside community elders, was piloted in select districts. This approach helped improve community mobilization and inform local microplanning, and will be expanded in future rounds.

To further encourage attendance, the programme is offering essential hygiene items at vaccination sites. In Kandahar city, for example, more than 214,000 soaps and diapers were distributed during the February campaign—an approach that successfully increased turnout among caregivers of young children.

Coordinating across borders

Cross-border coordination with Pakistan is also being actively strengthened. Joint case investigations, monthly information-sharing meetings, and biannual national-level reviews are now in place. Following the recent influx of Afghan returnees, the programme activated a contingency plan to scale up vaccination along the border—supported by additional teams and close coordination with UNHCR and IOM.

These efforts are further reinforced by the Health Dialogue facilitated by WHO between Afghanistan and Pakistan—an example of how public health priorities advancing tangible action, even in fragile settings.

Every campaign counts

While challenges remain—including missed children, misinformation, and insecurity—the polio programme in Afghanistan is demonstrating that with commitment, adaptation, and strong community engagement, progress is possible.

“Every campaign brings us closer,” said Shamsher Ali Khan, UNICEF Chief of Polio in Afghanistan. “If we can continue to reach every child, we can end polio in Afghanistan—and across the region.”

Mr Najibullah, District Polio Officer, Gyan district, Paktika

Mr Najibullah, District Polio Officer, Gyan district, Paktika

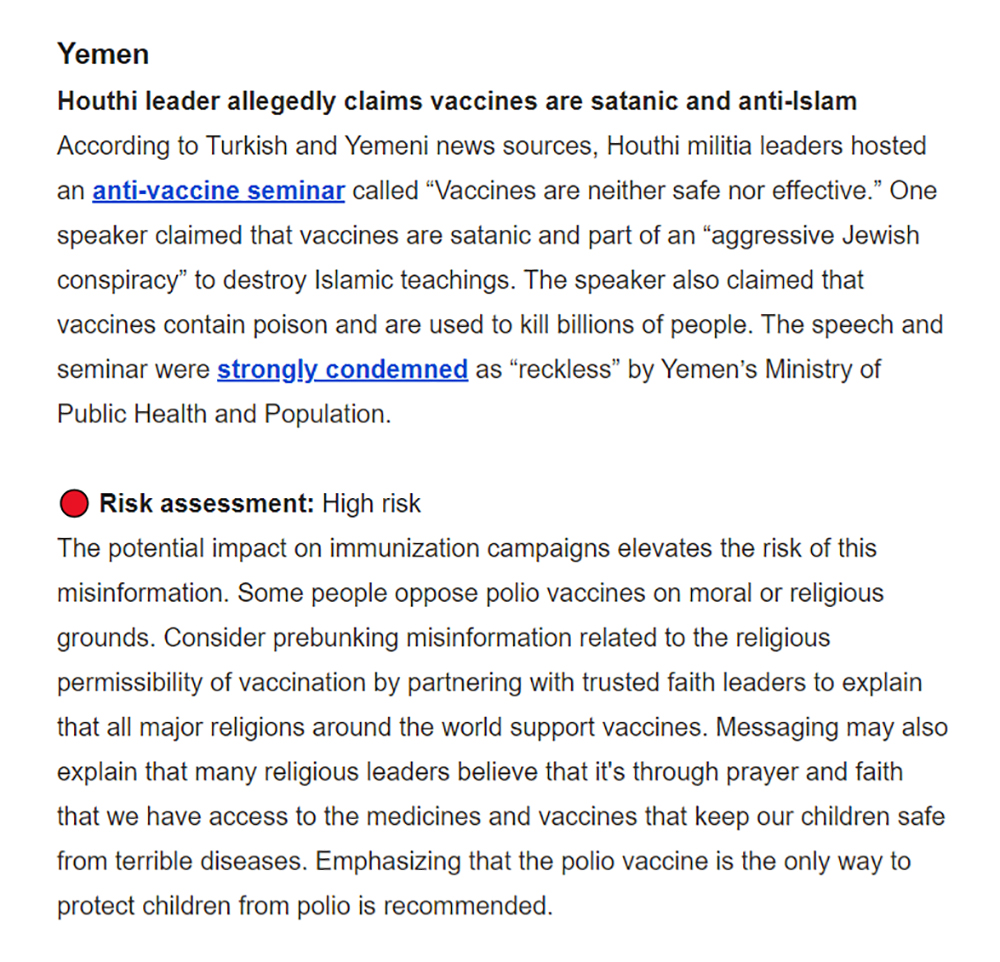

The DCE is made up of a central hub that tracks polio misinformation online, develops accurate messaging, and supports digital volunteers and UNICEF country offices. The hub is driven by a global team of experts spread across public health, social behaviour change, online social listening, advertising, content design and influencer marketing.

The DCE is made up of a central hub that tracks polio misinformation online, develops accurate messaging, and supports digital volunteers and UNICEF country offices. The hub is driven by a global team of experts spread across public health, social behaviour change, online social listening, advertising, content design and influencer marketing. Clear and accurate messages are crucial

Clear and accurate messages are crucial