For many of the women and men who spent their careers fighting polio, retirement offers not rest and relaxation, but a continuation of their life’s work towards eradication. Across the Eastern Mediterranean Region, once and forever polio fighters are inspiring the next generation of eradicators with their commitment to the cause, and belief in the benefits of a polio-free future.

Meet some of the Region’s most beloved polio fighters as they look back on their careers and try to capture their unusual motivation to continue their quest, as long as it takes.

Dr Ali Farah, Somalia

Back in 1997, during the devastating civil war, Dr Ali Farah started a pilot project to conduct Somalia’s first-ever national immunization days. Today, that pilot project is one of the reasons Somalia hasn’t seen a case of wild poliovirus in more than seven years.

Dr Farah retired in 2015 after years of hard work in a highly complex, volatile, and risky context. Yet he continues to fight polio by providing technical support to the polio programme team, participating in social mobilization activities and training district-level polio officers and vaccinators.

“I always feel that we must keep working to fight polio. It’s a humanitarian action,” he said. “Technical staff still call me occasionally to receive guidance about AFP cases and other technical areas. I feel so happy to provide advice and support when needed.”

Dr Farah has also utilized his long experience with the polio programme to support COVID-19 immunization in Somalia.

“This COVID-19 campaign wouldn’t succeed if there was no polio infrastructure. We used the polio system and network to make it happen,” he said.

Professor Elsadig Mahgoub, Sudan

After completing his bachelor’s degree in 1969, Professor Elsadig Mahgoub trained as a physician and epidemiologist. He devoted his career to infectious diseases, largely focusing on disease surveillance. In February 2000, he focused his efforts on polio, particularly surveillance for acute flaccid paralysis (APF), the primary symptom of paralytic polio.

Although he retired four years later, Prof Elsadig hasn’t stopped working or providing his technical support to polio programmes in Sudan and across the Region.

“I’m obliged to continue working. My enjoyment is when I see progress towards polio eradication,” he said. “The service we’re providing is critical. We always need to be vigilant to avoid any setback to our achievements towards polio eradication. When we end polio for good, then I will truly resign.”

Dr Mohammed Hajar, Yemen

Yemen’s Dr Mohammad Hajar is one of the oldest, most veteran health professionals in Yemen, having served the health sector and combated infectious diseases, including polio, for around 50 years.

In 1977, Dr Hajar was one of the founders of Yemen’s expanded programme on immunization. He played a major role in planning and conducting the first-ever polio campaigns in the country, and he contributed substantially to setting up the epidemiological surveillance system for polio and other diseases.

“Even after reaching retirement age in 2009, I continued to work for the polio programme, which I consider as one of my sons. Until now, I follow up and evaluate the activities of the immunization programme and polio campaigns,” said Dr Hajar.

“I had the privilege of working with nine WHO representatives and more than ten ministers of health in Yemen to help Yemen reach a polio-free status.”

Dr Ibrahim Barakat, Egypt

When Dr Ibrahim Barakat was appointed as a manager of Egypt’s expanded programme on immunization in 2000, he was determined to achieve something remarkable – a polio-free Egypt.

“It was a hard journey, but we did it. Egypt was declared polio-free in 2006,” he said.

In 2009, Dr Barakat retired, but he hardly rested. “I cannot stop working when it comes to polio eradication. I take great comfort in working hard to combat this disease whether in Egypt or any place in the world.”

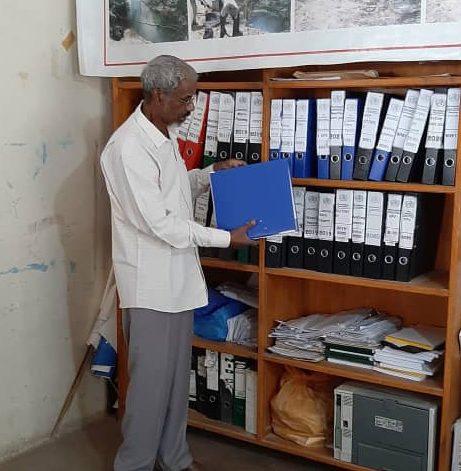

After 12 years of retirement, Dr Barakat still considers his office in the Ministry of Health as “a second home.”

“I continue going to the office every working day to plan, supervise and evaluate different polio activities, including polio vaccination campaigns, risk assessment and AFP surveillance. I can never be complacent,” he said.

“This is my life. My real retirement starts when I see this disease completely wiped out from all parts of the world.”

Mr. Alam and Mrs. Fatima, Pakistan

Khursheed Alam, 68, and Kaneez Fatima, 56, are a married couple who have spent 25 years working in the polio eradication programme in Batagram district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Pakistan.

Rain or shine, Mr. Alam and Mrs. Fatima have taken part in countless door-to-door vaccination campaigns, helping to vaccinate thousands of children.

“Now those little children have grown up, some have gotten married and had children who we have also vaccinated. This is fascinating and rewarding for us,” said Mr. Alam. “Wherever we go, people welcome us and don’t let us go without offering food.”

Mrs. Fatima personally knows every child in her neighborhood, including the newborns. She maintains close relationships with the mothers in her community and gives them health and hygiene advice.

Despite their age and medical complications such as asthma, their commitment to the polio programme remains strong.

“We take our work as a divine duty to serve our community for the sake of God. To see healthy children with smiles on their faces is our reward. This has kept us going for so long,” said Mrs. Fatima.

Dr Faten Kamel, Egypt

Dr Faten Kamel took a leading role in polio eradication efforts in the 1990s and early 2000s – years where the Global Polio Eradication Initiative made considerable gains against polio.

Growing up in Alexandria, Egypt, Dr Faten was exposed to the life-altering effects of polio on the people around her. She saw the human toll of the disease, and was inspired by the work of her father, a surgeon and Rotarian.

“We pushed the boundaries to make the programme more effective, shifting to house-to-house vaccination, detailed microplanning and mapping, retrieval of missed children and independent monitoring,” she said.

For Dr Faten, every child can, and must, be reached.

“If someone comes and says this area is inaccessible, this is not an answer for me. I ask: What should we do to reach? I like to make use of the ideas and experience that come from local people,” she said.

Dr Faten is proud to continue to be part of the polio eradication programme and looks forward to the day when polio eradication is achieved. After that, she plans to spend more time with her family in Australia.

“As a grandmother, I am especially determined to finish the job. I want my grandkids to grow up in a world free of polio. This will be my contribution to their futures.”