What is polio surveillance?

One of the most challenging aspects of polio eradication is timely disease surveillance: knowing where the poliovirus is lurking, so we can roll out targeted immunization activities quickly and effectively. With new tools, eradicators are getting the information they need in real time.

For the past three decades, there have been two approaches to find polio: passive and active surveillance. Passive surveillance involves health workers routinely reporting cases of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) as they find them in health facilities. Active surveillance takes place where there is a higher level of concern that polio might be present. Experts go to hospitals, clinics and even community healers to search out cases of AFP. This approach, often called active case searching, reduces the risk that cases are missed due to human error – people forgetting to report AFP or health care workers or community healers not knowing that they need to report the case.

However, in active case search the key steps of detecting, reporting and investigating the case might not always be happening consistently in all health facilities. There can be a delay of two months or more between a child being paralyzed, experts finding out and alerting the polio surveillance system. In an outbreak setting, this can be long enough for the virus to infect and paralyze more children, moving from one area to another. There was an obvious need to make the surveillance system even more reliable and time-sensitive to ensure the polio surveillance framework is as robust as ever.

Never missing a beat again

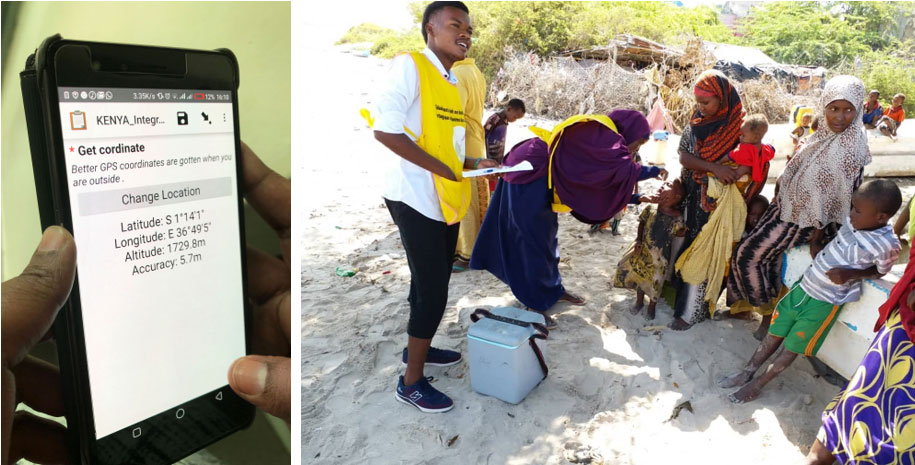

With the Integrated Surveillance and Routine Immunization Supervision system, surveillance officers use an app on their mobile phones to document active case searching as it happens, by tagging the location of every healthcare facility they visit and check.

In order to ensure that active search is conducted timely with real time evidence the polio surveillance systems in Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda, Eritrea, South Sudan, and Tanzania have adopted an easy-to-use, portable disease surveillance monitoring tool. It delivers unprecedented accuracy across huge areas. The best bit? Most people already have the basic component in their pockets: their mobile phones.

The tool is known as Integrated Surveillance and Routine Immunization Supervision. The idea is simple: surveillance officers use an app on their mobile phones to document active case searching as it happens, by tagging the location of every healthcare facility they visit and check.

“This provides real-time monitoring in the field. Previously, officers would report having done active case searching after the fact – like, ‘I was here and I did x, y, z’. But this is vulnerable to human error in remembering accurately. Sometimes, before we introduced it, someone would go to a distant, rural area and not be able to pinpoint their location on a map for others to follow up. Now, we are sure we are not missing things.” said Christopher Kamugisha, WHO’s Horn of Africa Outbreak Coordinator.

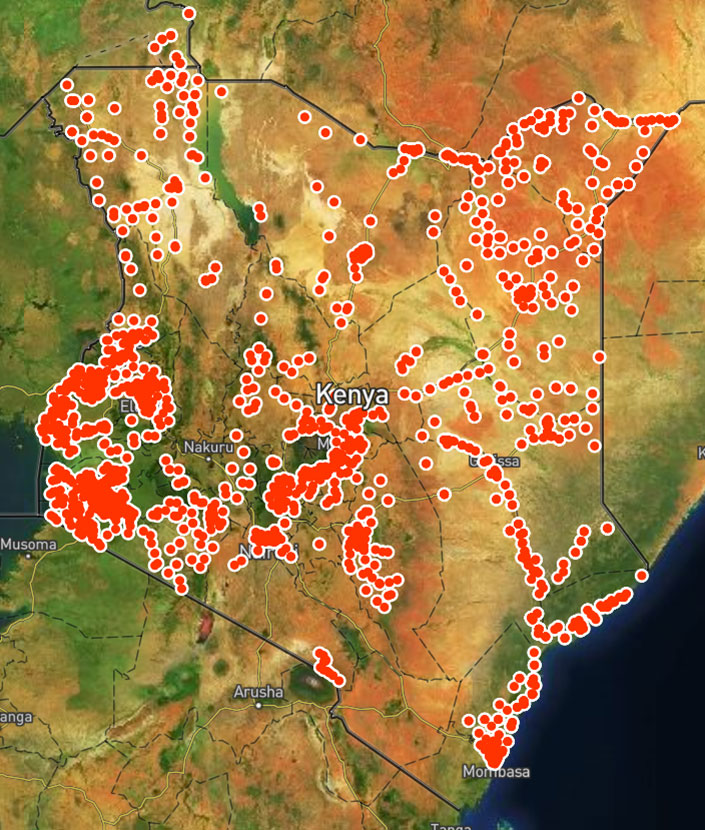

The map that is generated at the national level allows public health experts responding to the polio outbreak the opportunity to see where the gaps in surveillance for polio are in real time.

The app guides surveillance officers through a checklist (questions cover resources available at the facility, polio, measles and routine immunization) that they fill out and send then and there, using their mobile phones, even without an internet connection. It can also provide on-the-spot data analysis so that the surveillance officer can take immediate, evidence-based action.

With a swipe of the screen, users marry surveillance findings to the facility’s location and send the information to a centrally generated map. This gives staff at the national level a clearer picture of where surveillance is working and where it is not, including data on where possible polio cases are, so they know where to direct extra resources.

It also means health workers actively searching for AFP do not have to spend extra time ensuring the information gathered in the field is being shared with the right people for them to take action. For the ongoing outbreak of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus in the Horn of Africa, this means better disease surveillance – and a better chance to protect children against polio.