It has been 12 months since the last case due to wild poliovirus type 3 (WPV3) occurred anywhere in the world, in Yobe, Nigeria, on 10 November 2012. It is the lowest ever recorded levels of WPV3 transmission, and the world is beginning to ask: is this strain gone?

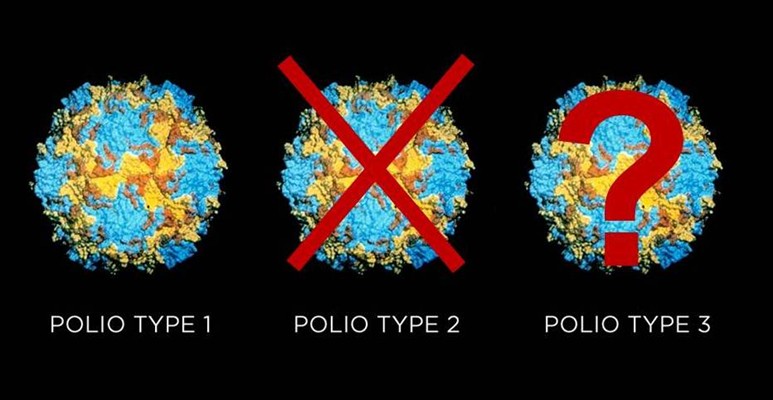

If so, it would be the second wild poliovirus strain to be eradicated, following wild poliovirus type 2 (WPV2) in 1999, and it would leave only wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1).

“I don’t think it’s gone, but it’s definitely at its lowest ever levels and if we keep up the pressure, it’s on its way out,” according to Chris Maher, Senior Scientist for Polio Eradication at the World Health Organization (WHO).

The danger with WPV3 is that it is less virulent than WPV1, Maher explains. It causes cases at a rate of approximately 1 in 2,000 infections, compared with 1 in 200 infections for WPV1. Causing fewer cases is a good thing, of course, but it also means that the virus can transmit more widely and longer, without being detected. “It’s a sneaky virus, in that sense, so we have to be cautious not to let it surprise us.” says Maher.

The other challenge is that the last known remaining WPV3 reservoirs (Khyber Agency in Pakistan, and Borno and Yobe states in northern Nigeria), are areas where access is compromised due to insecurity. Undetected circulation therefore cannot be fully ruled out. Efforts are ongoing to address these and other challenges, as part of national emergency action plans being implemented in both countries.

So for now, it is too soon to say that WPV3 has been eradicated. But what is clear is that with the current historic low levels, the world has a unique opportunity to get rid of the second strain of wild poliovirus. It would be a significant milestone for the global eradication effort, and would have significant operational benefits. Leaving only one wild poliovirus strain to target, the eradication of WPV3 would allow an all-out assault on the remaining strains of WPV1.